Punched tape

Punched tapes were used throughout the 19th and for much of the 20th centuries for programmable looms, teleprinter communication, for input to computers of the 1950s and 1960s, and later as a storage medium for minicomputers and CNC machine tools.

The resulting paper tape, also called a "chain of cards", was stronger and simpler both to create and to repair.

Many professional embroidery operations still refer to those individuals who create the designs and machine patterns as punchers even though punched cards and paper tape were eventually phased out in the 1990s.

In 1842, a French patent by Claude Seytre described a piano playing device that read data from perforated paper rolls.

[1][2] In the 1880s, Tolbert Lanston invented the Monotype typesetting system, which consisted of a keyboard and a composition caster.

The tape, punched with the keyboard, was later read by the caster, which produced lead type according to the combinations of holes in up to 31 positions.

In computer numerical control (CNC) machining applications, though paper tape has been superseded by digital memory, some modern systems still measure the size of stored CNC programs in feet or meters, corresponding to the equivalent length if the data were actually punched on paper tape.

[5] Australia's 1951 electronic computer, CSIRAC, used 3-inch (76 mm) wide paper tape with twelve rows.

The plastic tape was sometimes transparent, but usually was aluminized to make it opaque enough for use in high-speed optical readers.

Managing the disposal of chad was an annoying and complex problem, as the tiny paper pieces had a tendency to escape containment and to interfere with the other electromechanical parts of the teleprinter equipment.

Chad from oiled paper tape was particularly problematic, as it tended to clump and build up, rather than flowing freely into a collection container.

This enabled operators to read the tape without having to decipher the holes, which would facilitate relaying the message on to another station in the network.

Another disadvantage that emerged in time, was that there was no reliable way to read chadless tape in later high-speed readers which used optical sensing.

Binary data transfer to or from these minicomputers was often accomplished using a doubly encoded technique to compensate for the relatively high error rate of punches and readers.

Framing, addressing and checksum (primarily in ASCII hex characters) information helped with error detection.

Efficiencies of such an encoding scheme are on the order of 35–40% (e.g., 36% from 44 8-bit ASCII characters being needed to represent sixteen bytes of binary data per frame).

In the 1970s through the early 1980s, paper tape was commonly used to transfer binary data for incorporation in either mask-programmable read-only memory (ROM) chips or their erasable counterparts EPROMs.

A much more primitive as well as a much longer high-level encoding scheme was also used, BNPF (Begin-Negative-Positive-Finish),[12][13] also written as BPNF (Begin-Positive-Negative-Finish).

The ASCII "N" and "P" characters differed in four bit positions, providing excellent protection from single punch errors.

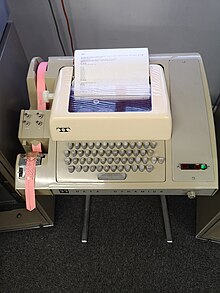

Even after the demise of Linotype and hot lead typesetting, many early phototypesetter devices utilized paper tape readers.

It looked like a strawberry stem remover that, pressed with thumb and forefinger, could punch out the remaining positions, one hole at a time.

Vernam ciphers were invented in 1917 to encrypt teleprinter communications using a key stored on paper tape.

During the last third of the 20th century, the National Security Agency (NSA) used punched paper tape to distribute cryptographic keys.

NSA has been trying to replace this method with a more secure electronic key management system (EKMS), but as of 2016[update], paper tape was apparently still being employed.