Quackery

[1] Psychiatrist and author Stephen Barrett of Quackwatch defines quackery as "the promotion of unsubstantiated methods that lack a scientifically plausible rationale" and more broadly as: "anything involving overpromotion in the field of health."

[6][7][8] American pediatrician Paul Offit has proposed four ways in which alternative medicine "becomes quackery":[9] Since it is difficult to distinguish between those who knowingly promote unproven medical therapies and those who are mistaken as to their effectiveness, United States courts have ruled in defamation cases that accusing someone of quackery or calling a practitioner a quack is not equivalent to accusing that person of committing medical fraud.

Grandiose claims were made for what could be humble materials indeed: for example, in the mid-19th century revalenta arabica was advertised as having extraordinary restorative virtues as an empirical diet for invalids; despite its impressive name and many glowing testimonials it was in truth only ordinary lentil flour, sold to the gullible at many times the true cost.

[15] A similar process occurred in other countries of Europe around the same time, for example with the marketing of Eau de Cologne as a cure-all medicine by Johann Maria Farina and his imitators.

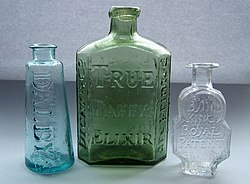

Patent medicines often contained alcohol or opium, which, while presumably not curing the diseases for which they were sold as a remedy, did make the imbibers feel better and confusedly appreciative of the product.

In 1875, the Pacific Medical and Surgical Journal complained: If Satan has ever succeeded in compressing a greater amount of concentrated mendacity into one set of human bodies above every other description, it is in the advertising quacks.

A recent arrival in San Francisco, whose name might indicate that he had his origin in the Pontine marshes of Europe, announces himself as the "Late examining physician of the Massachusetts Infirmary, Boston."

One among many examples is William Radam, a German immigrant to the US, who, in the 1880s, started to sell his "Microbe Killer" throughout the United States and, soon afterwards, in Britain and throughout the British colonies.

In fact, Radam's medicine was a therapeutically useless (and in large quantities actively poisonous) dilute solution of sulfuric acid, coloured with a little red wine.

[25] Radam's publicity material, particularly his books,[26] provide an insight into the role that pseudoscience played in the development and marketing of "quack" medicines towards the end of the 19th century.

"Dr." Sibley, an English patent medicine seller of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, even went so far as to claim that his Reanimating Solar Tincture would, as the name implies, "restore life in the event of sudden death".

This was the result of decades of campaigning by both government departments and the medical establishment, supported by a number of publishers and journalists (one of the most effective was Samuel Hopkins Adams, who wrote "The Great American Fraud" series in Collier's in 1905).

Language in the 1912 Sherley Amendment, meant to close this loophole, was limited to regulating claims that were false and fraudulent, creating the need to show intent.

The AMA's Department of Investigation closed in 1975, but their only archive open to non-members remains, the American Medical Association Health Fraud and Alternative Medicine Collection.

Most people with an e-mail account have experienced the marketing tactics of spamming – in which modern forms of quackery are touted as miraculous remedies for "weight loss" and "sexual enhancement", as well as outlets for medicines of unknown quality.

"[33] The president of the Indian Medical Association (IMA) in 2008 criticized the central government for failing to address the problem of quackery and for not framing any laws against it.

The Ministry of Ayush (expanded from Ayurveda, Yoga, Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha, Sowa-Rigpa and Homoeopathy), is purposed with developing education, research and propagation of indigenous alternative medicine systems in India.

Quality of research has been poor, and drugs have been launched without any rigorous pharmacological studies and meaningful clinical trials on Ayurveda or other alternative healthcare systems.

[49][50][51] Much of the research on postural yoga has taken the form of preliminary studies or clinical trials of low methodological quality;[52][53][54] there is no conclusive therapeutic effect except in back pain.

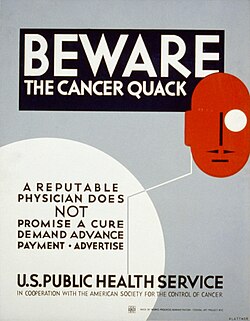

[62][63] While quackery is often aimed at the aged or chronically ill, it can be aimed at all age groups, including teens, and the FDA has mentioned[64] some areas where potential quackery may be a problem: breast developers, weight loss, steroids and growth hormones, tanning and tanning pills, hair removal and growth, and look-alike drugs.

Quackery is characterized by the promotion of false and unproven health schemes for profit and does not necessarily involve imposture, fraud, or greed.

The real issues in the war against quackery are the principles, including scientific rationale, encoded into consumer protection laws, primarily the U.S. Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

[68] To better address less regulated products, in 2000, US President Clinton signed Executive Order 13147 that created the White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine.

According to John C. Norcross et al. less is consensus about ineffective "compared to effective procedures" but identifying both "pseudoscientific, unvalidated, or 'quack' psychotherapies" and "assessment measures of questionable validity on psycho-metric grounds" was pursued by various authors.

For example, writing in The New York Times Magazine, Virginia Heffernan criticized WebMD for biasing readers toward drugs that are sold by the site's pharmaceutical sponsors, even when they are unnecessary.