Monarchy of Papua New Guinea

The first European attempt at colonisation was made in 1793 by Lieutenant John Hayes, a British naval officer, near Manokwari, now in Papua province, Indonesia.

[1] In February 1974, a year after self-government and discussions gathered momentum on the question for a date for independence, Queen Elizabeth II of Australia visited Papua New Guinea.

Chief Minister Michael Somare in his speech reaffirmed Papua New Guinea's desire and hope to join the Commonwealth of Nations upon independence.

[3][4] However, there was no indication of a continuing role for the Queen in independent Papua New Guinea when, in April 1975, it was decided that the head of state was to be a citizen of the country, who would be chosen by secret ballot.

[10] On 15 August 1975, the Constituent Assembly formally adopted the Constitution, invited the Queen to become head of state and asked her to accept Parliament's nomination of John Guise as governor-general of Papua New Guinea.

This legislation limits the succession to the natural (i.e. non-adopted), legitimate descendants of Sophia, Electress of Hanover, and stipulates that the monarch cannot be a Roman Catholic, and must be in communion with the Church of England upon ascending the throne.

Though these constitutional laws, as they apply to Papua New Guinea, still lie within the control of the British parliament, both the United Kingdom and Papua New Guinea cannot change the rules of succession without the unanimous consent of the other realms, unless explicitly leaving the shared monarchy relationship; a situation that applies identically in all the other realms, and which has been likened to a treaty amongst these countries.

[40] This body of law altogether gives Papua New Guinea a parliamentary system of government under a constitutional monarchy, wherein the role of the monarch and governor-general is both legal and practical, but not political.

As such, it is for the Cabinet to decide how to use the Royal Prerogative, command the Papua New Guinea Defence Force, summon and prorogue parliament and call elections.

[49] The governor-general, to maintain the stability of the government of Papua New Guinea, appoints as prime minister the leader of the political party which gains the support of a majority in Parliament after a general election.

[52] Given that sovereignty vests in the citizenry and not the head of state, Papua New Guinea is unique among Commonwealth realms in that legislative authority rests solely with the National Parliament as opposed to the Crown.

[59] The Papua New Guinean monarch, on the advice of the National Executive Council, can also grant immunity from prosecution, exercise the royal prerogative of mercy, and pardon offences against the Crown, either before, during, or after a trial.

[65] St Edward's Crown appears on Papua New Guinea's Defence Force rank insignia, which illustrates the monarchy as the locus of authority.

Members of the Defence Force have often participated and represented Papua New Guinea at various royal events, including the Platinum Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II,[66][67] and the coronation of King Charles III.

[68] Members of the royal family also act as colonels-in-chief of various regiments, reflecting the Crown's relationship with the Defence Force through participation in military ceremonies both at home and abroad.

[69] In 2012, Charles, dressed in the forest green uniform of the regiment, presented troops with new colours at the Sir John Guise Stadium in Port Moresby.

[78][79] The Princess Royal, during her visit for the Queen's Platinum Jubilee in 2022, mentioned that she had private conversations with her family about Tok Pisin, saying, "you won't be surprised to hear that we compare our memories of the odd bits of pidgin that we remember".

A Crown is also depicted as a royal symbol on various medals and awards, which reflects the monarch's place as the fount of honour—the formal head of the Papua New Guinea honours system.

In the painting, the Queen is shown wearing a Gerua, an important ceremonial headdress traditionally worn by Chieftains in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea.

[89][90] To commemorate the Golden Jubilee of Elizabeth II in 2002, a Fine Arts Exhibition, entitled 20 Portraits and other Works, was held in Papua New Guinea in June 2002.

The winning portrait by painter Laben John was presented as a gift to the Queen by Jean Kekedo, Papua New Guinean High Commissioner to the UK, on 16 July 2002.

[91][92] To mark Papua New Guinea's 50th anniversary of independence in 2025, an art competition was launched for all schools in Port Moresby, which required students to design a mural of King Charles III.

[97][98] Queen Elizabeth II visited Papua New Guinea for the first time in February 1974, along with Prince Philip, Princess Anne, Captain Mark Phillips and Lord Louis Mountbatten.

[99] The Post Courier editorial of 27 February 1974, remarked:[100] The affinity between British royalty and Papua New Guinea today has more the flavor of the line at the supermarket checkout than that of monarch and subject.

[99] In her speech, the Queen said that when she accepted the office of Head of State, she had hoped that the Crown could play a part in helping to establish and maintain unity.

They arrived in Port Moresby, where more than 100,000 people in traditional dress greeted the couple, before an official welcome from Prime Minister Michael Somare, followed by a state reception.

[27][96] During their time in the country, the Prince and the Duchess met church, charity, and community volunteers, cultural groups, and members of the Papua New Guinea Defence Force in and near Port Moresby.

[106] The Princess and her husband Vice Admiral Sir Timothy Laurence carried out various engagements, including visits to a Catholic boarding school, St John Ambulance PNG, the Bomana War Cemetery, Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery, Port Moresby General Hospital, Vabukori, and Hanuabada.

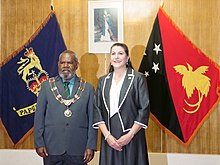

[110] In 2022, the year of the Platinum Jubilee of Elizabeth II, Governor-General Sir Bob Dadae said that Papua New Guineans were "graciously honoured and proud" to have the Queen as their head of state.

[112] In 1983, the final report of the General Constitutional Commission (GCC) recommended that the monarchy be replaced with a ceremonial presidency under an indigenous head of state.