Quest for the historical Jesus

[1] Conventionally, since the 18th century three scholarly quests for the historical Jesus are distinguished, each with distinct characteristics and based on different research criteria, which were often developed during each specific phase.

While textual analysis of biblical sources had taken place for centuries, these quests introduced new methods and specific techniques to establish the historical validity of their conclusions.

[15][16][17] Conventionally, since the 18th century three scholarly quests for the historical Jesus have been distinguished, each with distinct characteristics and based on different research criteria, which were often developed during each specific phase.

[18] The threefold terminology uses the literature selectively, poses an incorrect periodization of research which fails to note the socio-cultural context of the socalled first quest, which began with a critical questioning of Christian origins predating Reimarus, in contrast to what Albert Schweitzer had claimed.

[1][24] One of the earliest notable publications in the field was by Hermann Reimarus (1694–1768) who portrayed Jesus as a less than successful political figure who assumed his destiny was to place God as the king of Israel.

[1][2] Strauss viewed the miraculous accounts of Jesus' life in the gospels in terms of myths which had arisen as a result of the community's imagination as it retold stories and represented natural events as miracles.

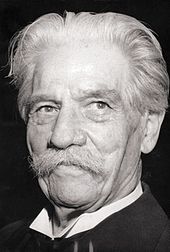

[1][33] Albert Schweitzer wrote in The Quest of the Historical Jesus (1906; 1910) that Strauss's arguments "filled in the death-certificates of a whole series of explanations which, at first sight, have all the air of being alive, but are not really so".

Among the works that appeared after Strauss, Ernest Renan's book Vie de Jesus, which combined scholarship with sentimental and novelistic psychological interpretation, was very successful and had eight re-printings in three months.

[1] Renan merged gospel narratives with his own psychological interpretations, e.g. that Jesus preached a "sweet theology of love" in Galilee, but turned into a revolutionary once he encountered the establishment in Jerusalem.

[34] Wrede wrote on the Messianic Secret theme in the Gospel of Mark and argued that it was a method used by early Christians to explain Jesus not claiming himself as the Messiah.

In 1912, Shirley Jackson Case noted that within the last decade, doubts about Jesus' existence had been advanced in several quarters, but nowhere so insistently as in Germany where the skeptical movement had become a regular propaganda, "Its foremost champion is Arthur Drews, professor of philosophy in Karlsruhe Technical High School.

Since the appearance of his Christusmythe in 1909 the subject has been kept before the public by means of debates held in various places, particularly at some important university centers such as Jena, Marburg, Giessen, Leipzig, Berlin.

[23][24][48][49] Stanley Porter states that Schweitzer's critique only ended the "romanticized and overly psychologized" studies into the life of Jesus, and other research continued.

Much of the stronger claims, and the emphasis on the redeeming power of Christ's death on the Cross, could be seen as reworkings by St. Paul, who was probably influenced strongly by the Graeco-Roman traditions.

The actual problem is arguably that critics use them inappropriately, trying to describe the history of minute portions of the Gospel text, rather than a true flaw in the historical logic of the criteria.

The Son of Man is Jesus' most common self-designation in the Gospels, yet none of the New Testament epistles use this expression, nor is there any evidence that the disciples or the early church did.

[97][98][99][100][101] A series of language-based criteria have been developed since 1925, when the 'criterion of Semitic language phenomena' was first introduced,[102] followed by and linked to the 'criterion of Palestinian environment' by scholars such as Joachim Jeremias (1947).

[112] John P. Meier (1991) defined a 'criterion of traces of Aramaic' and a 'criterion of Palestinian environment', noting they are closely connected and warning that they are best applied in the negative sense, as the linguistic, social, and cultural environment of Palestine did not suddenly change after the death of Jesus, and so traditions invented inside Palestine in the first few decades after Jesus's death may – misleadingly – appear contextually authentic.

[115] As historian Will Durant explains: Despite the prejudices and theological preconceptions of the evangelists, they record many incidents that mere inventors would have concealed – the competition of the apostles for high places in the Kingdom, their flight after Jesus' arrest, Peter's denial, the failure of Christ to work miracles in Galilee, the references of some auditors to his possible insanity, his early uncertainty as to his mission, his confessions of ignorance as to the future, his moments of bitterness, his despairing cry on the cross.

[116]These and other possibly embarrassing events, such as the discovery of the empty tomb by women, Jesus' baptism by John, and the crucifixion itself, are seen by this criterion as lending credence to the supposition the gospels contain some history.

[129] The 21st century has witnessed an increase in scholarly interest in the integrated use of archaeology as an additional research component in arriving at a better understanding of the historical Jesus by illuminating the socio-economic and political background of his age.

[135][136][137] David Gowler states that an interdisciplinary scholarly study of archeology, textual analysis and historical context can shed light on Jesus and his teachings.

[13][14] In his 1906 book The Quest of the Historical Jesus, Albert Schweitzer noted the similarities of the portraits to the scholars who construct them and stated that they are often "pale reflections of the researchers" themselves.

For instance, James Crossley and Robert J. Myles argue that a rigorous and sober materialist approach can help counter anachronism and scholars' interest in talking about themselves when doing historical Jesus studies.

[157] Robert J. Myles has looked at how contemporary scholars claim Jesus was "subversive" while in actuality they bolster a non-subversive liberal view of him, similar to the phenomenon of the Hipster.

[164][165] On the other side of the coin, historian Michael Licona says there is a "secular bias that ...often goes unrecognized to the extent such beliefs are ...considered to be undeniable truths."

[148][118][149][178][179][180] New Testament scholar John Kloppenborg Verbin says the lack of uniformity in the application of the criteria, and the absence of agreement on methodological issues concerning them, have created challenges and problems.

[187] Donald Akenson, Professor of Irish Studies in the department of history at Queen's University has argued that, with very few exceptions, the historians attempting to reconstruct a biography of the man Jesus of Nazareth apart from the mere facts of his existence and crucifixion have not followed sound historical practices.

"[15][196] By way of contrast, James Crossley and Robert J. Myles argue that a rigorous and sober materialist approach can help counter anachronism and scholars' interest in talking about themselves when doing historical Jesus studies.

"[205] Representative of critical scholarship today are the comments of James Crossley and Robert J. Myles who "are sceptical about what we can know with confidence" and "prefer to think in terms of whether ideas about Jesus were early or late and whether they were particular to his geographical location or beyond.