Quilago

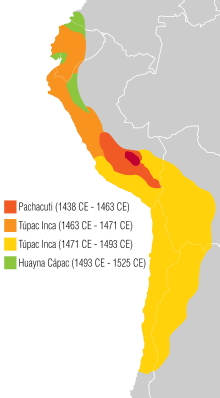

[5] As queen, Quilago formed a united front with neighboring indigenous societies to militarily resist the expansion of the Inca.

[2] Quilago's military coalition managed to keep the invading Inca at bay for two years,[8] during which many troops were killed and the bridges across the river destroyed in fire.

Huayna Capac, the Sapa Inca, tactically withdrew his forces, telling his soldiers that he had been promised victory by the Sun God and that they ought not to be intimidated by an army led by a woman.

[16] Anthropologists Frank Salamone and Sabine Hyland consider this story to be a folkloric explanation for the use of shaft tombs in Quito.

[20] The title of "Quilago" has since been passed down into the surnames of northern Andean peoples, including Abaquilago, Angoquilago, Arraquilago, Imbaquilago, Paraquilago and Quilango.

[2] As the final ruler of Cochasquí, Quilago has taken a central position in archaeological narratives of the Inca conquest of Ecuador.

[21] The story of Quilago's reign has also become an origin myth in the history of Ecuador, drawing on contemporary ideas of indigeneity and gender to construct an Ecuadorian national identity.

[22] In this national narrative, Atahualpa has been held to be the "first true Ecuadorian"[10] or a "son of Ecuador"[3] due to his mixed heritage from Quilago and Huayna Capac.

[23] In the 1930s, this theory provoked the Armed Forces of Ecuador to search for her remains, in order to "reclaim the mother of the nation".