Quinto (drum)

It is used as the lead drum in Cuban rumba styles such as guaguancó, yambú, columbia and guarapachangueo, and it is also present in congas de comparsa.

[1] The optimum expression of quinto phrasing is shaped by its interaction with the dance and the song, in other words, the complete social event, which is rumba.

There are natural pauses in the cadence of the verses, typically one or two measures in length, where the quinto can play succinct phrases in the “holes” left by the singer.

Once the chorus (or montuno section) of the song begins, the phrases of the quinto interact with the dancers more than the lead singer.

1924) states: "Although there is a structure of rhythm in columbia, yambú, or guaguancó, the good rumbero will always follow the dancer’s steps and at the same time express his own individuality.

"[3] With an emphasis on competition and individual creativity, the rhythmic vocabulary of quinto has evolved into a rich and pliable art form.

The rhythmic phrasing heard in solos by percussion and other instruments in Cuban popular music, salsa, and Latin jazz, are often based on the quinto vocabulary.

Quinto phrasing is also used as a means of varying the ostinato conga drum part called tumbao (see songo music).

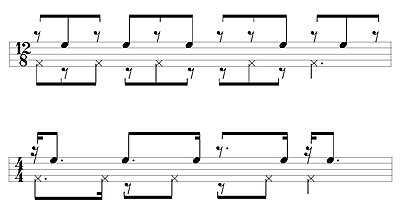

[citation needed] The lock melody while constantly varied, maintains a specific relationship to clave, and corresponds to the basic side-to side rumba dance steps.

The attack points of the lock and the basic steps are contained within a single cycle of clave (the key pattern of rumba).

Columbia has cultural and musical ties to the Abakuá, a secret society from the Cross River region of present day southern Nigeria and northern Cameroon.

The rhythmic phrasing of the abakuá lead drum bonkó enchemiyá is similar, and in some instances, identical to the quinto.

Besides the typical rumba context, the lock is found in a form of Afro-Cuban sacred drumming called cajón pa’ los muertos.

[10] The following phrase concludes on 3-e. Havana born Mongo Santamaría (1917-2003) was a tremendous quintero, and at one time, the most famous conga drummer in the world.

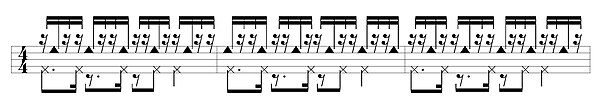

[14]By alternating between the lock and the cross, the quinto creates larger rhythmic phrases that expand and contract over several clave cycles.

The great Los Muñequintos quintero Jesús Alfonso (1949–2009) described this phenomenon as a man getting “drunk at a party, going outside for awhile, and then coming back inside.

Even with today’s flashy percussion solos, where snare rudiments and other highly developed techniques are used, analysis of the prevailing accents will reveal an underlying quinto structure, of which crossing is the most important.