r-process

[1] This amounts to almost a gram of free neutrons in every cubic centimeter, an astonishing number requiring extreme locations.

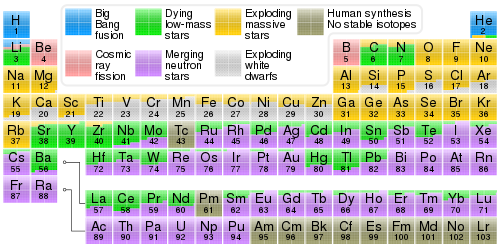

[3] The relative contribution of each of these sources to the astrophysical abundance of r-process elements is a matter of ongoing research as of 2018[update].

[4] A limited r-process-like series of neutron captures occurs to a minor extent in thermonuclear weapon explosions.

The r-process contrasts with the s-process, the other predominant mechanism for the production of heavy elements, which is nucleosynthesis by means of slow captures of neutrons.

[6] This became the foundation of a study by Fred Hoyle, who hypothesized that conditions in the core of collapsing stars would enable nucleosynthesis of the remainder of the elements via rapid capture of densely packed free neutrons.

However, there remained unanswered questions about equilibrium in stars that was required to balance beta-decays and precisely account for abundances of elements that would be formed in such conditions.

These observations also implied that rapid neutron capture occurred faster than beta decay, and the resulting abundance peaks were caused by so-called waiting points at magic numbers.

[13] He and subsequent astronomers showed that the pattern of heavy-element abundances in the earliest metal-poor stars matched that of the shape of the solar r-process curve, as if the s-process component were missing.

Either interpretation, though generally supported by supernova experts, has yet to achieve a totally satisfactory calculation of r-process abundances because the overall problem is numerically formidable.

As this re-expands and cools, neutron capture by still-existing heavy nuclei occurs much faster than beta-minus decay.

These so-called waiting points are characterized by increased binding energy relative to heavier isotopes, leading to low neutron capture cross sections and a buildup of semi-magic nuclei that are more stable toward beta decay.

[18] Waiting point nuclei are then allowed to beta decay toward stability before further neutron capture can occur,[1] resulting in a slowdown or freeze-out of the reaction.

[17] Decreasing nuclear stability terminates the r-process when its heaviest nuclei become unstable to spontaneous fission, when the total number of nucleons approaches 270.

[22] The r-process also occurs in thermonuclear weapons, and was responsible for the initial discovery of neutron-rich almost stable isotopes of actinides like plutonium-244 and the new elements einsteinium and fermium (atomic numbers 99 and 100) in the 1950s.

The ejected material must be relatively neutron-rich, a condition which has been difficult to achieve in models,[2] so that astrophysicists remain uneasy about their adequacy for successful r-process yields.

The bulk of this material seems to consist of two types: hot blue masses of highly radioactive r-process matter of lower-mass-range heavy nuclei (A < 140 such as strontium)[27] and cooler red masses of higher mass-number r-process nuclei (A > 140) rich in actinides (such as uranium, thorium, and californium).

Such duration of luminosity would not be possible without heating by internal radioactive decay, which is provided by r-process nuclei near their waiting points.

Current astrophysical models suggest that a single neutron star merger event may have generated between 3 and 13 Earth masses of gold.