R.U.R.

stands for Rossumovi Univerzální Roboti (Rossum's Universal Robots,[1] a phrase that has been used as a subtitle in English versions).

[2] The play had its world premiere on 2 January 1921 in Hradec Králové;[3] it introduced the word "robot" to the English language and to science fiction as a whole.

(As living creatures of artificial flesh and blood, that later terminology would call androids, the playwright's 'roboti' differ from later fictional and scientific concepts of inorganic constructs.)

Helena, the daughter of the president of a major industrial power, arrives at the island factory of Rossum's Universal Robots.

After meeting the heads of R.U.R., Helena reveals that she is a representative of the League of Humanity, an organization that wishes to liberate the robots.

Helena and Domin reminisce about the day they met and summarize the last ten years of world history, which has been shaped by the new worldwide robot-based economy.

Echoing the story of the Tower of Babel, the characters discuss whether creating national robots who were unable to communicate beyond their languages would have been a good idea.

The characters lament the end of humanity and defend their actions, despite the fact that their imminent deaths are a direct result of their choices.

The robots storm the factory and kill all the humans except for Alquist, the company's Clerk of the Works (Head of Construction).

Playing a hunch, Alquist threatens to dissect Primus and then Helena; each begs him to take him- or herself and spare the other.

HELENA: Oh, please forgive me... His robots resemble more modern conceptions of man-made life forms, such as the Replicants in Blade Runner, the "hosts" in the Westworld TV series and the humanoid Cylons in the re-imagined Battlestar Galactica, but in Čapek's time there was no conception of modern genetic engineering (DNA's role in heredity was not confirmed until 1952).

There are descriptions of kneading-troughs for robot skin, great vats for liver and brains, and a factory for producing bones.

One critic has described Čapek's robots as epitomizing "the traumatic transformation of modern society by the First World War and the Fordist assembly line".

In an article in Lidové noviny, Karel Čapek named his brother Josef as the true inventor of the word.

[16] The name Rossum is an allusion to the Czech word rozum, meaning "reason", "wisdom", "intellect" or "common sense".

[18] After being postponed, it premiered at the city's National Theatre on 25 January 1921, although an amateur group had by then already presented a production.

Later that year performance rights for the U.S. and Canada were sold to the New York Theatre Guild, perhaps during Lawrence Langner's visit to Britain.

The omission of some lines may have been censorship from the Lord Chamberlain's Office, or self-censorship in anticipation of this, while some other changes might have been made by Čapek himself if Selver was working from a manuscript copy.

[note 3] An edition of Playfair's adaptation was published by the Oxford University Press in 1923, and Selver went on to write a satiric novel One, Two, Three (1926) based on his experiences getting R.U.R.

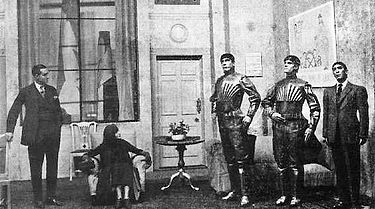

In the first performance, Domin was portrayed by Basil Sydney, Marius by John Merton, Hallemeier by Moffat Johnston, Alquist by Louis Calvert, Busman by Henry Travers, the robot Helena by antiwar activist Mary Crane Hone in her Broadway debut, and Primus by John Roche.

[24] This version was based on Playfair's adaptation, but omitted the characters Fabry and Hallemeier, and included several of the New York Theatre Guild revisions.

[18] In the 1920s, the play was performed in a number of American and British cities, including the Theatre Guild "Road" in Chicago and Los Angeles during 1923.

[note 4] This letter is held in Southern Illinois University Carbondale's Morris Library, along with an English translation of these lines, perhaps in Marsh's handwriting.

[23] In 1989, a new, unabridged translation by Claudia Novack-Jones, based on Čapek's revised 1921 version, restored the elements of the play eliminated by Playfair.

The book also contained a collection of essays reflecting on the play's legacy from scientists and scholars who work in artificial life and robotics.

He saw the play as part comedy, and ending with faith that humanity would survive albeit in a different form, while the critics often considered it to be pessimistic or nihilistic, and purely either an updated Frankenstein, an anti-capitalist satire, or a critique of contemporary political ideologies.