R. A. B. Mynors

Sir Roger Aubrey Baskerville Mynors FBA (28 July 1903 – 17 October 1989) was an English classicist and medievalist who held the senior chairs of Latin at the universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

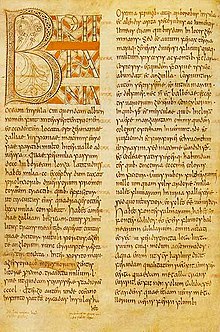

[1] He was an expert on palaeography, and has been credited with unravelling a number of highly complex manuscript relationships in his catalogues of the Balliol and Durham Cathedral libraries.

Roger Aubrey Baskerville Mynors was born in Langley Burrell, Wiltshire,[2] on 28 July 1903 into a family of Herefordshire gentry.

His mother was Margery Musgrave, and his father, Aubrey Baskerville Mynors, was an Anglican clergyman and rector of Langley Burrell, who had been secretary to the Pan-Anglican Congress, held in London in 1908.

[2] Attending the college at the same time as the literary critic Cyril Connolly, the musicologist Jack Westrup, the future Vice-Chancellor of the University of Oxford, Walter Fraser Oakeshott, and the historian Richard Pares, he was highly successful in his academic studies.

Mynors's interest in codicology gave rise to a close co-operation with the medievalists Richard William Hunt and Neil Ripley Ker.

Having relocated to England because of the increasing discrimination against German Jews, Fraenkel was a leading exponent of Germany's scholarly tradition.

They maintained a close friendship, which exposed Mynors to other German philologists, including Rudolf Pfeiffer and Otto Skutsch.

[12] In 1940, after a brief return to Balliol, British involvement in the Second World War led to his being employed at the Exchange Control Department of Her Majesty's Treasury responsible for the administration of foreign currency transactions.

[2] At Balliol, Mynors taught from 1926 until 1944,[2] a time during which he mentored a number of future scholars, including the Wittgenstein expert David Pears and the classicist Donald Russell.

At Cambridge, Mynors was required to lecture extensively on Latin literature and to supervise research students, a task of which he had little experience.

The duties of his university post left little time to get involved in the activities of the college, which led Mynors to regret his departure from Oxford, going so far as to describe the decision as a "fundamental error" in a personal letter.

[22] In the 17 years he spent at the college, Mynors sought to maintain its position as a centre of excellence in the Classics and fostered contacts with a new generation of Latinists, including E. J. Kenney, Wendell Clausen, Leighton Durham Reynolds, R. J. Tarrant and Michael Winterbottom.

For the Balliol archivist Bethany Hamblen, this interest typifies the importance Mynors gave to formal features when evaluating hand-written books.

In the introduction, Mynors offered new insights into the complex manuscript tradition without resolving the fundamental question of how the original text was expanded in later copies.

Taking a conservative stance on the problems posed by Catullus's text, Mynors did not print any modern emendations unless they corrected obvious scribal errors.

[31] Contrary to his conservative instincts, he rejected the traditional archaising orthography of the manuscripts in favour of normalised Latin spelling.

[31] For the reviewer Philip Levine, Mynors's edition sets itself apart from previous texts by its scrutiny of a "large bulk" of unexamined manuscripts.

[35] He enlarged the manuscript base by drawing on 13 minor witnesses from the ninth century[36] and added an index of personal names.

[36] Given the incomplete state of the Aeneid, Vergil's epic poem on the wanderings of Aeneas, Mynors departed from his cautious editorial stance by printing a small number of modern conjectures.

Collation of the Saint Petersburg Bede, an 8th-century manuscript unknown to Plummer, allowed Mynors to construct a new version of the M tradition.

[39] Although he did not append a detailed critical apparatus and exegetical notes, his analysis of the textual history was praised by the Church historian Gerald Bonner as "lucid" and "excellently done".

[42][43] In spite of its accomplishments, the classicist Patricia Johnston has noted that the commentary fails to engage seriously with contemporary scholarship on the text,[43] such as the tension between optimistic and pessimistic[c] readings.