RAF Bomber Command aircrew of World War II

Under Article XV of the 1939 Air Training Agreement, squadrons belonging officially to the RCAF, RAAF, and RNZAF were formed, equipped and financed by the RAF, for service in Europe.

A wireless operator/air gunner wore a single-winged aircrew flying badge with a wreath containing the letters AG or S on his tunic, above his left breast pocket denoting his trade specialisation and a cloth arm patch featuring lightning bolts.

[36] Bristol Blenheim twin-engined light bomber – used in daylight or night operations and usually crewed by three airmen, a pilot, an observer and a wireless operator/air gunner in a dorsal power-operated gun turret.

The Bomb Aimer was usually often a commissioned officer, he wore a single-winged aircrew flying badge with a wreath containing the letter B on his tunic, above his left breast pocket denoting his trade specialisation.

These men graduated training schools to earning a single-winged aircrew flying badge over a wreath containing the letters S on his tunic, above his left breast pocket denoting his trade specialisation as "signaller".

The Short Stirling was withdrawn from service with RAF Bomber Command in 1944 being used mainly thereafter for SOE support missions,[56] mine laying and towing gliders of airborne troops.

[64] As the war progressed pilots and observers (later navigators and bomb aimers) were considerably more likely to be commissioned officers before the end of their operational tours, keeping pace with the enormous rate of losses; men could be promoted three times in a year.

[75][76] One of RAF Bomber Command's oldest casualties in action was Flight Sergeant Kadir Nagalingam, a 48-year-old from Sri Lanka, who was killed on the night 14–15 October 1944 while serving as a wireless operator aboard an Avro Lancaster of No.

101 Squadron RAF "Set Operator" aboard an Avro Lancaster lost on the night 12–13 August 1944, Sergeant Hans Heinz Schwarz (serving as Blake) who was a 19-year-old Jewish man taking enormous risks to fight for his adopted country.

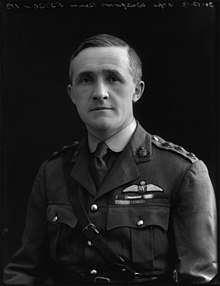

37 Squadron RAF on 31 May 1940 during the Battle of France was Pilot Officer Sir Arnold Talbot Wilson, KCIE, CSI, CMG, DSO, MP a 56-year-old former lieutenant colonel in the Indian Army who had joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve.

[91][92] A number of seventeen-year-olds were lost flying operationally with RAF Bomber Command during World War II, examples being Sergeant Ronald Lewis serving as a wireless operator/air gunner aboard a No.

During the day crews would briefly "air test" the aircraft assigned to them to ensure that it was working properly and that their personal equipment, oxygen supply, heated flight suits and machine guns were all ready.

[104][105]As soon as the ground crew commenced preparing the aircraft, they would be able to estimate what the night's operation was likely to be based on the payload of bombs (or sea mines) coupled with the fuel load to be pumped into the wing tanks.

Briefings usually commenced during the afternoons, and for reasons of security the bomber base would be closed down to all but the most necessary traffic in or out to reduce to a minimum any leakage of intelligence which might help to forewarn the enemy,[109] even public telephones were padlocked.

After briefings had been completed aircrew would be permitted free time to prepare themselves, to write "just in case I don't get back" letters to parents, wives and children and to relax or sleep if they were able before their meal which was often referred to as "last supper".

[109][120][121] As the time approached crews collected their parachutes and Mae West life preservers from the Parachute Section,[122] and "suited up" in the "crew room" or locker room climbing into their flying suits ensuring that everything was comfortable ready for a flight which could be ten or twelve hours long,[123] memoirs mention that lucky charms were checked and double checked, some men were quieter while others were noisy and putting a brave face on to cover their uncertainty.

[141] Once airborne every airman had to hope that his oxygen mask and supply functioned properly when it was switched on at 5,000 feet and did not suffer from icing in the frigid temperatures at high altitude; their electrically heated flying suits, boots and gloves were completely necessary to avoid frostbite throughout the year.

[143] On the outward-trip it was normal for crews to mention over the intercom any landmarks that they observed to assist the navigator and once over the North Sea the air gunners would be cleared to test their guns firing off brief bursts.

Depending on the course to the target the bombers might overfly a number of belts of anti-aircraft artillery and search lights, radar assemblies and listening positions attracting barrages of fire and would be persistently pursued harried and attacked by night-fighters.

[151] The Ruhr Valley was about 35 minutes flying time from the Dutch coast and here the first bombers in the stream would be met with intense anti-aircraft fire and extremely efficient searchlights working closely together.

[155][156] When possible RAF Bomber Command would arrange a diversionary attack which was known as a "spoof raid", using a small secondary force, often aircraft from Operational Training Units, in an attempt to confuse the enemy night fighter controllers and draw the Luftwaffe night fighters of the Kammhuber line sufficiently far away from the main bomber stream that they would have expended so much fuel before the deception was identified that they would have to land to refuel and may be unable to intercept the main force.

The bomber pilot would typically then turn sharply and dive before heading on a course for home as a countermeasure to avoid predicted anti-aircraft fire or night fighter attack.

An early return due to engine or equipment failure or crew sickness could result in an interview with the commanding officer to ensure that negligence or lack of fighting spirit were not involved.

This Pathfinder leader was known as the master bomber and usually had a second-in-command flying in support in case he was shot down or failed to mark the target accurately and it required a second set of "markers".

[205][206][207] Aircrew adopted a fatalistic attitude, and it was "not the done thing" to discuss losses of friends or roommates, although they would half-jokingly ask each other "can I have your bicycle if you get the chop" or "can I have your eggs and bacon at breakfast if you don't get back tomorrow?"

[223] Some RAF Bomber Command airmen received awards for their gallantry in specific actions or for their sustained courage facing the terrible odds against their surviving a full tour of operations.

[227][228] Many biographies and auto-biographies of aircrew record that, facing a very limited life expectancy, airmen frequently adopted mascots and superstitions, holding to a belief that if they adhered to a particular custom or carried a specific talisman with them, then they would "get home in time for breakfast".

[117][126] Amongst those frequently mentioned are having a family photograph attached to their crew position inside the bomber, carrying a rabbit's foot or teddy bear, wearing a particular scarf around the neck,[229] urinating on the tail wheel of the aircraft before takeoff,[230] or always donning their flying kit on the same sequence.

The fear was not groundless, as a newly arrived airman from a training unit might be used as a temporary replacement for their highly experienced crewman, and a momentary hesitation in calling for evasive action in a pending night-fighter attack did result in bombers being lost.

[238][239] The process was considered harsh and was deeply resented by the aircrews themselves, who rarely spoke of "LMF" situations; even decades after the war, few memoirs give more than an occasional mention of the issue.