R v Penguin Books Ltd

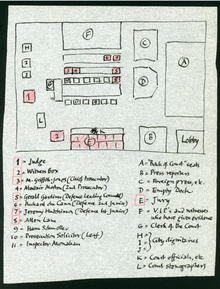

The trial took place over six days, in No 1 court of the Old Bailey, between 20 October and 2 November 1960 with Mervyn Griffith-Jones[c] prosecuting, Gerald Gardiner counsel for the defence[d] and Laurence Byrne presiding.

The trial was a test case of the defence of public good provision under section 4 of the Act which was defined as a work "in the interests of science, literature, art or learning, or of other objects of general concern".

Consequently, the resultant Act made specific provision for a defence of public good, broadly defined as a work of artistic or scientific merit, intended to exclude literature from the scope of the law while still permitting the prosecution of pornography or such works that would under section 2 of the Act "tend to deprave and corrupt persons likely to read it".

[h] Lawrence's novel had been the subject of three drafts before the final unexpurgated typewritten transcript was submitted to the Florentine printers on 9 March 1928 with the intention of publishing a private limited edition of 1000 copies.

[10] He also conceded that Lawrence was a writer of stature and that the book may have had some literary value but the obscenity of its language, its recommendation of what appears to be adulterous promiscuity and that the plot is mere padding for descriptions of sexual intercourse[11] outweighed any such defence.

That "Lawrence's message, as you have heard, was that the society of his day in England was sick, he thought, and the sickness from which it was suffering was the result of the machine age, the 'bitch-goddess Success', the importance that everybody attached to money, and the degree to which the mind had been stressed at the expense of the body; and that what we ought to do was to re-establish personal relationships, the greatest of which was the relationship between a man and a woman in love, in which there was no shame and nothing wrong, nothing unclean, nothing which anybody was not entitled to discuss.

The defence called John Robinson, the Bishop of Woolwich, to elicit "[w]hat, if any, are the ethical merits of this book?"

[17] In testimony that was later seen to have had a deciding influence on the trial[j] the sociologist and lecturer in English Literature Richard Hoggart was called to testify to the literary value of Lady Chatterley's Lover.

We have no word in English for this act which is not either a long abstraction or an evasive euphemism, and we are constantly running away from it, or dissolving into dots, at a passage like that.

"[18] Cross-examining for the prosecution, Griffith-Jones pursued Hoggart's previous description of the book as "highly virtuous if not puritanical".

The proper meaning of it, to a literary man or to a linguist, is somebody who belongs to the tradition of British Puritanism generally, and the distinguishing feature of that is an intense sense of responsibility for one's conscience.

[22] The judge gave his opinion that the defence was not justified in calling evidence to prove that there was no intent to deprave and corrupt, that defence could not produce other books with respect to evidence of the present book's obscenity rather than literary merit and that expert testimony could not be called as to the public good of the work which was a matter for the jury.

You may think that place rather a less burden upon the prosecution than hitherto, that it rather widens the scope of this Act than otherwise, for now, irrespective of whether the person reading the book is one of a rather dull or perhaps retarded or stupid intellect, one whose mind may be open to such influences, there is not any such restricted class.

Members of the jury, the short answer to that view of the matter is this, which I think I put to one witness: what is there in the book to suggest that if the sexual intercourse between lady Chatterley and Mellors had not eventually turned out to be successful she would not have gone on and on and on elsewhere until she did find it?

[33] Richard Hoggart in his autobiography wrote of the trial: "It has been entered on the agreed if conventional list of literary judgements as the moment at which the confused mesh of British attitudes to class, to literature, to the intellectual life, and to censorship, publicly clashed as rarely before – to the confusion of more conservative attitudes.

"[34] Philip Larkin referred to the trial in his 1974 poem "Annus Mirabilis": Sexual intercourse began In nineteen sixty-three (which was rather late for me) – Between the end of the Chatterley ban And the Beatles' first LP.