Rabbinic Judaism

During this time currents of Judaism were influenced by Hellenistic philosophy developed from the 3rd century BCE, notably among the Jewish diaspora in Alexandria, culminating in a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible known as the Septuagint.

The people, who did not want to continue to be governed by a Hellenized dynasty, appealed to Rome for intervention, leading to a total Roman conquest and annexation of the country, see Iudaea province.

The attractiveness of Christianity may, however, have suffered a setback with its being explicitly outlawed in the 80s CE by Domitian as a "Jewish superstition", while Judaism retained its privileges as long as members paid the Fiscus Judaicus.

On the other hand, mainstream Judaism began to reject Hellenistic currents, outlawing use of the Septuagint (see also the Council of Jamnia).

[citation needed] In the later part of the Second Temple period (2nd century BCE), the Second Commonwealth of Judea (Hasmonean Kingdom) was established and religious matters were determined by a pair (zugot) which led the Sanhedrin.

The Hasmonean Kingdom ended in 37 BCE but it is believed that the "two-man rule of the Sanhedrin" lasted until the early part of the 1st century CE during the period of the Roman province of Judea.

The development of an oral tradition of teaching called the tanna would be the means by which the faith of Judaism would sustain the fall of the Second Temple.

[3] Jewish messianism has its root in the apocalyptic literature of the 2nd to 1st centuries BCE, promising a future "anointed" leader or Messiah to resurrect the Israelite "Kingdom of God", in place of the foreign rulers of the time.

Their vision of Jewish law as a means by which ordinary people could engage with the sacred in their daily lives, provided them with a position from which to respond to all four challenges, in a way meaningful to the vast majority of Jews.

[citation needed] Following the destruction of the Temple, Rome governed Judea through a Procurator at Caesarea and a Jewish Patriarch.

In 132, the Emperor Hadrian threatened to rebuild Jerusalem as a pagan city dedicated to Jupiter, called Aelia Capitolina.

Whether because they had no wish to fight, or because they could not support a second messiah in addition to Jesus, or because of their harsh treatment by Bar Kokhba during his brief reign, these Christians also left the Jewish community around this time.

[9] After the suppression of the revolt the vast majority of Jews were sent into exile; shortly thereafter (around 200), Judah haNasi edited together judgments and traditions into an authoritative code, the Mishnah.

[citation needed] The survival of Pharisaic or Rabbinic Judaism is attributed to Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkai, the founder of the Yeshiva (religious school) in Yavne.

Yavneh replaced Jerusalem as the new seat of a reconstituted Sanhedrin, which reestablished its authority and became a means of reuniting Jewry.

Temple ritual was replaced with prayer service in synagogues which built upon practices of Jews in the diaspora dating back to the Babylonian exile.

As the rabbis were required to face two shattering new realities, Judaism without a Temple (to serve as the center of teaching and study) and Judea without autonomy, there was a flurry of legal discourse and the old system of oral scholarship could not be maintained.

[10] The theory that the destruction of the Temple and subsequent upheaval led to the committing of Oral Law into writing was first explained in the Epistle of Sherira Gaon and often repeated.

Much rabbinic Jewish literature concerns specifying what behavior is sanctioned by the law; this body of interpretations is called halakha (the way).

The Talmud contains discussions and opinions regarding details of many oral laws believed to have originally been transmitted to Moses.

As the rabbis were required to face a new reality, that of Judaism without a Temple (to serve as the location for sacrifice[12] and study) and Judea without autonomy, there was a flurry of legal discourse, and the old system of oral scholarship could not be maintained.

[13] The theory that the destruction of the Temple and subsequent upheaval led to the committing of Oral Torah into writing was first explained in the Epistle of Sherira Gaon and often repeated.

[citation needed] Much rabbinic Jewish literature concerns specifying what behavior is sanctioned by the law; this body of interpretations is called halakha (the way).

As the rabbis were required to face a new reality—mainly Judaism without a Temple (to serve as the center of teaching and study) and Judea without autonomy—there was a flurry of legal discourse and the old system of oral scholarship could not be maintained.

[10][15] The earliest recorded oral law may have been of the midrashic form, in which halakhic discussion is structured as exegetical commentary on the Pentateuch (Torah).

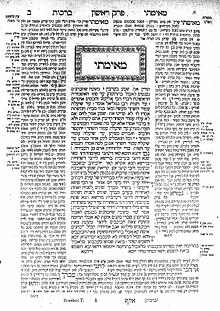

But an alternative form, organized by subject matter instead of by biblical verse, became dominant about the year 200 CE, when Rabbi Judah haNasi redacted the Mishnah (משנה).

According to the Iggeret of Sherira Gaon, after the tremendous upheaval caused by the destruction of the Temple and the Bar Kokhba revolt, the Oral Torah was in danger of being forgotten.

Authorities are divided on whether Judah haNasi recorded the Mishnah in writing or established it as an oral text for memorisation.

In the three centuries following the redaction of the Mishnah by Judah ha-Nasi (c. 200 CE), rabbis throughout Palestine and Babylonia analyzed, debated and discussed that work.

Rather, it sees the Judaism of this period as continuing organically from the religious and cultural heritage of the Israelites, stemming from the Law given to Moses at Sinai onwards.