Race (human categorization)

Social conceptions and groupings of races have varied over time, often involving folk taxonomies that define essential types of individuals based on perceived traits.

[35] Although commonalities in physical traits such as facial features, skin color, and hair texture comprise part of the race concept, this linkage is a social distinction rather than an inherently biological one.

A large body of scholarship has traced the relationships between the historical, social production of race in legal and criminal language, and their effects on the policing and disproportionate incarceration of certain groups.

In this way the idea of race as we understand it today came about during the historical process of exploration and conquest which brought Europeans into contact with groups from different continents, and of the ideology of classification and typology found in the natural sciences.

The 1735 classification of Carl Linnaeus, inventor of zoological taxonomy, divided the human species Homo sapiens into continental varieties of europaeus, asiaticus, americanus, and afer, each associated with a different humour: sanguine, melancholic, choleric, and phlegmatic, respectively.

[64] In the last two decades of the 18th century, the theory of polygenism, the belief that different races had evolved separately in each continent and shared no common ancestor,[65] was advocated in England by historian Edward Long and anatomist Charles White, in Germany by ethnographers Christoph Meiners and Georg Forster, and in France by Julien-Joseph Virey.

Virtually all physical anthropologists agree that Archaic Homo sapiens (A group including the possible species H. heidelbergensis, H. rhodesiensis, and H. neanderthalensis) evolved out of African H. erectus (sensu lato) or H.

[70][verification needed] In the early 20th century, many anthropologists taught that race was an entirely biological phenomenon and that this was core to a person's behavior and identity, a position commonly called racial essentialism.

[73] New studies of culture and the fledgling field of population genetics undermined the scientific standing of racial essentialism, leading race anthropologists to revise their conclusions about the sources of phenotypic variation.

Wright argued: "It does not require a trained anthropologist to classify an array of Englishmen, West Africans, and Chinese with 100% accuracy by features, skin color, and type of hair despite so much variability within each of these groups that every individual can easily be distinguished from every other.

"[88] Evolutionary biologist Alan Templeton (2013) argued that multiple lines of evidence falsify the idea of a phylogenetic tree structure to human genetic diversity, and confirm the presence of gene flow among populations.

They argued that this a priori grouping limits and skews interpretations, obscures other lineage relationships, deemphasizes the impact of more immediate clinal environmental factors on genomic diversity, and can cloud our understanding of the true patterns of affinity.

From one end of this range to the other, there is no hint of a skin color boundary, and yet the spectrum runs from the lightest in the world at the northern edge to as dark as it is possible for humans to be at the equator.In part, this is due to isolation by distance.

[96] As the anthropologists Leonard Lieberman and Fatimah Linda Jackson observed, "Discordant patterns of heterogeneity falsify any description of a population as if it were genotypically or even phenotypically homogeneous".

[112][113] Joanna Mountain and Neil Risch cautioned that while genetic clusters may one day be shown to correspond to phenotypic variations between groups, such assumptions were premature as the relationship between genes and complex traits remains poorly understood.

She argues that it is actually just a "local category shaped by the U.S. context of its production, especially the forensic aim of being able to predict the race or ethnicity of an unknown suspect based on DNA found at the crime scene".

Serre & Pääbo (2004) argued for smooth, clinal genetic variation in ancestral populations even in regions previously considered racially homogeneous, with the apparent gaps turning out to be artifacts of sampling techniques.

Nonetheless, Rosenberg et al. (2005) stated that their findings "should not be taken as evidence of our support of any particular concept of biological race ... Genetic differences among human populations derive mainly from gradations in allele frequencies rather than from distinctive 'diagnostic' genotypes."

"[130] Anthropologist Stephan Palmié has argued that race "is not a thing but a social relation";[131] or, in the words of Katya Gibel Mevorach, "a metonym", "a human invention whose criteria for differentiation are neither universal nor fixed but have always been used to manage difference".

[152] Thus, the historical construction of race in Brazilian society dealt primarily with gradations between persons of majority European ancestry and little minority groups with otherwise lower quantity therefrom in recent times.

[166] Lieberman et al. in a 2004 study researched the acceptance of race as a concept among anthropologists in the United States, Canada, the Spanish speaking areas, Europe, Russia and China.

[168] A 1998 "Statement on 'Race'" composed by a select committee of anthropologists and issued by the executive board of the American Anthropological Association, which they argue "represents generally the contemporary thinking and scholarly positions of a majority of anthropologists", declares:[169] In the United States both scholars and the general public have been conditioned to viewing human races as natural and separate divisions within the human species based on visible physical differences.

The results were as follows: A line of research conducted by Cartmill (1998), however, seemed to limit the scope of Lieberman's finding that there was "a significant degree of change in the status of the race concept".

[174] According to the 2000 University of Wyoming edition of a popular physical anthropology textbook, forensic anthropologists are overwhelmingly in support of the idea of the basic biological reality of human races.

We realize that in the extremes of our transit – Moscow to Nairobi, perhaps – there is a major but gradual change in skin color from what we euphemistically call white to black, and that this is related to the latitudinal difference in the intensity of the ultraviolet component of sunlight.

The authors concluded, "The concept of race, masking the overwhelming genetic similarity of all peoples and the mosaic patterns of variation that do not correspond to racial divisions, is not only socially dysfunctional but is biologically indefensible as well (pp.

He wrote that "Based upon my findings I argue that the category of race only seemingly disappeared from scientific discourse after World War II and has had a fluctuating yet continuous use during the time span from 1946 to 2003, and has even become more pronounced from the early 1970s on".

"[3] The committee co-chair Charmaine D. Royal and Robert O. Keohane of Duke University agreed in the meeting: "Classifying people by race is a practice entangled with and rooted in racism.

Similarly, forensic anthropologists draw on highly heritable morphological features of human remains (e.g. cranial measurements) to aid in the identification of the body, including in terms of race.

[224] In 2010, philosopher Neven Sesardić argued that when several traits are analyzed at the same time, forensic anthropologists can classify a person's race with an accuracy of close to 100% based on only skeletal remains.

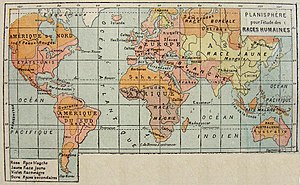

- Mongoloid race, shown in yellow and orange tones

- Caucasoid race, in light and medium grayish spring green - cyan tones

- Negroid race, in brown tones

- Dravidians and Sinhalese , in olive green and their classification is described as uncertain