Adaptive radiation

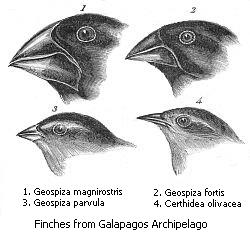

In evolutionary biology, adaptive radiation is a process in which organisms diversify rapidly from an ancestral species into a multitude of new forms, particularly when a change in the environment makes new resources available, alters biotic interactions or opens new environmental niches.

[1][2] Starting with a single ancestor, this process results in the speciation and phenotypic adaptation of an array of species exhibiting different morphological and physiological traits.

[4] Sources of ecological opportunity can be the loss of antagonists (competitors or predators), the evolution of a key innovation, or dispersal to a new environment.

have somewhat longer beaks than the ground finches that serve the dual purpose of allowing them to feed on Opuntia cactus nectar and pollen while these plants are flowering, but on seeds during the rest of the year.

[13][14][15] These lakes are believed to be home to about 2,000 different species of cichlid, spanning a wide range of ecological roles and morphological characteristics.

[14] The three species of Altolamprologus are also piscivores, but with laterally compressed bodies and thick scales enabling them to chase prey into thin cracks in rocks without damaging their skin.

[14] A number of Tanganyika's cichlids are shell-brooders, meaning that mating pairs lay and fertilize their eggs inside of empty shells on the lake bottom.

[14] A number of other highly specialized Tanganyika cichlids exist aside from these examples, including those adapted for life in open lake water up to 200m deep.

[15] Malawi's cichlids span a similarly range of feeding behaviors to those of Tanganyika, but also show signs of a much more recent origin.

However, a number of particularly divergent species are known from Malawi, including the piscivorous Nimbochromis livingtonii, which lies on its side in the substrate until small cichlids, perhaps drawn to its broken white patterning, come to inspect the predator - at which point they are swiftly eaten.

Victoria is famously home to many piscivorous cichlid species, some of which feed by sucking the contents out of mouthbrooding females' mouths.

[18] Victoria's cichlids constitute a far younger radiation than even that of Lake Malawi, with estimates of the age of the flock ranging from 200,000 years to as little as 14,000.

[13] Hawaii has served as the site of a number of adaptive radiation events, owing to its isolation, recent origin, and large land area.

[19] An entire clade of Hawaiian honeycreepers, the tribe Psittirostrini, is composed of thick-billed, mostly seed-eating birds, like the Laysan finch (Telespiza cantans).

The most famous example of adaptive radiation in plants is quite possibly the Hawaiian silverswords, named for alpine desert-dwelling Argyroxiphium species with long, silvery leaves that live for up to 20 years before growing a single flowering stalk and then dying.

[22] This means that the silverswords evolved on Hawaii's modern high islands, and descended from a single common ancestor that arrived on Kauai from western North America.

The Hawaiian lobelioids are significantly more speciose than the silverswords, perhaps because they have been present in Hawaii for so much longer: they descended from a single common ancestor who arrived in the archipelago up to 15 million years ago.

[25] On each of these islands, anoles have evolved with such a consistent set of morphological adaptations that each species can be assigned to one of six "ecomorphs": trunk–ground, trunk–crown, grass–bush, crown–giant, twig, and trunk.

Much like in the case of the cichlids of the three largest African Great Lakes, each of these islands is home to its own convergent Anolis adaptive radiation event.

The pseudoxyrhophiine snakes of Madagascar have evolved into fossorial, arboreal, terrestrial, and semi-aquatic forms that converge with the colubroid faunas in the rest of the world.