Classical radicalism

During the 19th century in the United Kingdom, continental Europe and Latin America, the term radical came to denote a progressive liberal ideology inspired by the French Revolution.

In 19th-century France, radicalism was originally the extreme left of the day, in contrast to the social-conservative liberalism of Moderate Republicans and Orléanist monarchists and the anti-parliamentarianism of the Legitimists and Bonapartists.

[10] Victorian era Britain possessed both trends: In England the Radicals were simply the left wing of the Liberal coalition, though they often rebelled when the coalition's socially conservative Whigs resisted democratic reforms, whereas in Ireland Radicals lost faith in the ability of parliamentary gradualism to deliver egalitarian and democratic reform and, breaking away from the main body of liberals, pursued a radical-democratic parliamentary republic through separatism and insurrection.

By the middle of the century, parliamentary Radicals joined with others in the Parliament of the United Kingdom to form the Liberal Party, eventually achieving reform of the electoral system.

Candidates for the House of Commons stood as Whigs or Tories, but once elected formed shifting coalitions of interests rather than splitting along party lines.

At general elections, the vote was restricted to property owners in constituencies which were out of date and did not reflect the growing importance of manufacturing towns or shifts of population, so that in many rotten borough seats could be bought or were controlled by rich landowners while major cities remained unrepresented.

The "Middlesex radicals" were led by the politician John Wilkes, an opponent of war with the colonies who started his weekly publication The North Briton in 1764 and within two years had been charged with seditious libel and expelled from the House of Commons.

Middlesex and Westminster were among the few parliamentary constituencies with a large and socially diverse electorate including many artisans as well as the middle class and aristocracy and along with the county association of Yorkshire led by the Reverend Christopher Wyvill were at the forefront of reform activity.

Major John Cartwright also supported the colonists, even as the American Revolutionary War began and in 1776 earned the title of the "Father of Reform" when he published his pamphlet Take Your Choice!

In 1780, a draft programme of reform was drawn up by Charles James Fox and Thomas Brand Hollis and put forward by a sub-committee of the electors of Westminster.

In November 1783, he took his opportunity and used his influence in the House of Lords to defeat a Bill to reform the British East India Company, dismissed the government and appointed William Pitt the Younger as his Prime Minister.

Proposals Pitt made in April 1785 to redistribute seats from the "rotten boroughs" to London and the counties were defeated in the House of Commons by 248 votes to 174.

Dismayed by the inability of British parliamentarianism to introduce the root-and-branch democratic reforms desired, Irish Radicals channelled their movement into a republican form of nationalism that would provide equality as well as liberty.

Popular Radicals were quick to go further than Paine, with Newcastle schoolmaster Thomas Spence demanding land nationalisation to redistribute wealth in a penny periodical he called Pig's Meat in a reference to Burke's phrase "swinish multitude".

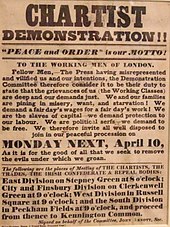

Radical organisations sprang up, such as the London Corresponding Society of artisans formed in January 1792 under the leadership of the shoemaker Thomas Hardy to call for the vote.

They issued a manifesto demanding universal male suffrage with annual elections and expressing their support for the principles of the French Revolution.

The numbers involved in these movements were small and most wanted reform rather than revolution, but for the first time working men were organising for political change.

The publications of William Cobbett were influential and at political meetings speakers like Henry Hunt complained that only three men in a hundred had the vote.

Writers like the radicals William Hone and Thomas Jonathan Wooler spread dissent with publications such as The Black Dwarf in defiance of a series of government acts to curb circulation of political literature.

In Scotland, agitation over three years culminated in an attempted general strike and abortive workers' uprising crushed by government troops in the "Radical War" of 1820.

Despite initial disagreements, after their failure their cause was taken up by the middle class Anti-Corn Law League founded by Richard Cobden and John Bright in 1839 to oppose duties on imported grain which raised the price of food and so helped landowners at the expense of ordinary people.

The Tories under Lord Derby and Benjamin Disraeli took office and the new government decided to "dish the Whigs" and "take a leap in the dark" to take the credit for the reform.

As a minority government, they had to accept radical amendments and Disraeli's Reform Act 1867 almost doubled the electorate, giving the vote even to working men.

The monarch enjoyed broad personal powers, his ministers were irresponsible before parliament; the separation of powers was minimal; freedom of press and association were limited; the principle of universal suffrage was undermined by the fact that the largely Catholic south, despite possessing two-thirds of the population, received as many seats to the Estates-General (parliament) as the smaller Protestant north; and the Dutch authorities were suspected of forcing Protestantism onto Catholics.

Those who remained intransigent in believing that the French Revolution needed to be completed through a republican regime based on parliamentary democracy and universal suffrage therefore tended to call themselves "Radicals" – a term meaning 'Purists'.

This experience would mark French Radicalism for the next century, prompting permanent vigilance against all those who – from Marshall Mac-Mahon to General De Gaulle – were suspected of seeking to overthrow the constitutional, parliamentary regime.

The first half of the Third Republic saw several events that caused them to fear a far-right takeover of parliament that might end democracy, as Louis-Napoléon had: Marshall Mac-Mahon's self-coup in 1876, the General Boulanger crisis in the 1880s, the Dreyfus Affair in the 1890s.

Ultimately the installation of the Fifth Republic in 1958, and the subsequent emergence of a two-party system based on the Socialist and Gaullist movements, destroyed the niche for an autonomous Radical party.

Typical of these classical Radicals are 19th century such as the United Irishmen in the 1790s, Young Irelanders in the 1840s, Fenian Brotherhood in the 1880s, as well as Sinn Féin, and Fianna Fáil in the 1920s.

Later political expressions of classical Radicalism centered around the Populist Party, composed of rural western and southern farmers who were proponents of policies such as railroad nationalization, free silver, expansion of voting rights and labor reform.