Radio Act of 1912

The 1906 International Radiotelegraph Convention, held in Berlin, called for countries to license their stations, and although United States representatives had signed this agreement, initially the U.S. Senate did not ratify the treaty.

The issue gained importance twelve days later due to the sinking of the Titanic,[2] and the new law would also incorporate provisions of the London Convention signed on July 5, 1912, although the United States had not yet ratified the new treaty.

The Act was unusual in including numerous regulations within the text of the bill, in addition to providing a general regulatory framework.

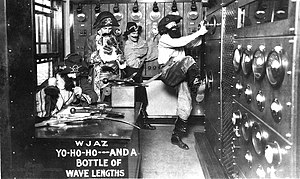

[8][9] Herbert Hoover became the Secretary of Commerce in March 1921, and thus assumed primary responsibility for shaping radio broadcasting during its earliest days, which was a difficult task in a fast-changing environment.

To aid decision-making, he sponsored a series of four national conferences from 1922 to 1925, where invited industry leaders participated in setting standards for radio in general.

The Department of Commerce planned to request a review by the Supreme Court, but the case was rendered moot when Intercity decided to shut down the New York City station.

[12] On April 16, 1926, Judge James H. Wilkerson's ruling stated that, under the 1912 Act, the Commerce Department in fact could not limit the number of broadcasting licenses issued, or designate station frequencies.