Rado graph

The names of this graph honor Richard Rado, Paul Erdős, and Alfréd Rényi, mathematicians who studied it in the early 1960s; it appears even earlier in the work of Wilhelm Ackermann (1937).

The Rado graph can also be constructed non-randomly, by symmetrizing the membership relation of the hereditarily finite sets, by applying the BIT predicate to the binary representations of the natural numbers, or as an infinite Paley graph that has edges connecting pairs of prime numbers congruent to 1 mod 4 that are quadratic residues modulo each other.

The Rado graph is uniquely defined, among countable graphs, by an extension property that guarantees the correctness of this algorithm: no matter which vertices have already been chosen to form part of the induced subgraph, and no matter what pattern of adjacencies is needed to extend the subgraph by one more vertex, there will always exist another vertex with that pattern of adjacencies that the greedy algorithm can choose.

The Rado graph was first constructed by Ackermann (1937) in two ways, with vertices either the hereditarily finite sets or the natural numbers.

They proved that it has infinitely many automorphisms, and their argument also shows that it is unique though they did not mention this explicitly.

[4] In one of Ackermann's original 1937 constructions, the vertices of the Rado graph are indexed by the hereditarily finite sets, and there is an edge between two vertices exactly when one of the corresponding finite sets is a member of the other.

A similar construction can be based on Skolem's paradox, the fact that there exists a countable model for the first-order theory of sets.

[6] Another construction of the Rado graph shows that it is an infinite circulant graph, with the integers as its vertices and with an edge between each two integers whose distance (the absolute value of their difference) belongs to a particular set

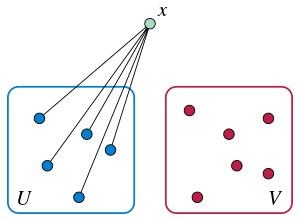

[9] The Rado graph satisfies the following extension property: for every two disjoint finite sets of vertices

, by the Chinese remainder theorem, the numbers that are quadratic residues modulo every prime in

form a periodic sequence, so by Dirichlet's theorem on primes in arithmetic progressions this number-theoretic graph has the extension property.

[6] The extension property can be used to build up isomorphic copies of any finite or countably infinite graph

[11] This method forms the basis for a proof by induction, with the 0-vertex subgraph as its base case, that every finite or countably infinite graph is an induced subgraph of the Rado graph.

Then, by applying the extension property twice, one can find isomorphic induced subgraphs

By repeating this process, one may build up a sequence of isomorphisms between induced subgraphs that eventually includes every vertex in

[14] The statement about pointwise stabilizers is called the small index property,[14] and proving it required showing that for every finite graph

[16] The construction of the Rado graph as an infinite circulant graph shows that its symmetry group includes automorphisms that generate a transitive infinite cyclic group.

The difference set of this construction (the set of distances in the integers between adjacent vertices) can be constrained to include the difference 1, without affecting the correctness of this construction, from which it follows that the Rado graph contains an infinite Hamiltonian path whose symmetries are a subgroup of the symmetries of the whole graph.

is formed from the Rado graph by deleting any finite number of edges or vertices, or adding a finite number of edges, the change does not affect the extension property of the graph.

Cameron (2001) gives the following short proof: if none of the parts induces a subgraph isomorphic to the Rado graph, they all fail to have the extension property, and one can find pairs of sets

The first-order language of graphs is the collection of well-formed sentences in mathematical logic formed from variables representing the vertices of graphs, universal and existential quantifiers, logical connectives, and predicates for equality and adjacency of vertices.

For instance, the condition that a graph does not have any isolated vertices may be expressed by the sentence

[24] The extension property of the Rado graph may be expressed by a collection of first-order sentences

labeled vertices, then the probability that such a sentence will be true for the chosen graph approaches one in the limit as

Because of this 0-1 law, it is possible to test whether any particular first-order sentence is modeled by the Rado graph in a finite amount of time, by choosing a large enough value of

It is unlikely that determining whether the Rado graph models a given sentence can be done more quickly than exponential time, as the problem is PSPACE-complete.

[31] Given that it is also in a finite relational language, ultrahomogeneity is equivalent to its theory having quantifier elimination and being ω-categorical.

[17] The Rado graph, the Henson graphs and their complements, disjoint unions of countably infinite cliques and their complements, and infinite disjoint unions of isomorphic finite cliques and their complements are the only possible countably infinite homogeneous graphs.

Truss (1985) investigates the automorphism groups of this more general family of graphs.

many vertices and shows that even in the absence of CH, there may exist a universal graph of size