Railway gun

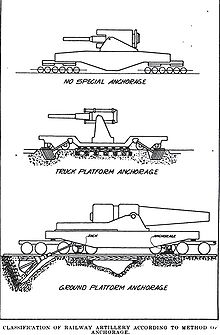

With few exceptions these types of mounts require some number of outriggers, stabilisers, or earth anchors to keep them in place against the recoil forces and are generally more suitable for smaller guns.

It is returned to battery, or the firing position, by either helical springs or by air in a pneumatic recuperator cylinder that is compressed by the force of recoil.

This is the most common method used for lighter railway guns and for virtually all field artillery designed after the French introduced their Canon de 75 modèle 1897.

Return to battery is effected either by gravity, through the use of inclined rails, which the gun and carriage have run up, by springs, or even by rubber bands, on some improvised mounts.

The American post–World War I assessment of railway artillery praised its ruggedness, ease of manufacture and convenience in service, but acknowledged its unsuitability for smaller guns, due to excessive time of operation and lack of traverse, and that it was not suitable for the largest howitzers firing at high angles because of the enormous trunnion forces.

[3] The great advantage of this method is that it requires minimal preparation and can fire from any suitable section of curved track.

The horizontal component would be alleviated by either sliding recoil or rail clamps, guys or struts to secure the mount in place.

[6][7] The first railway gun used in combat was a banded 32-pounder Brooke naval rifle mounted on a flat car and shielded by a sloping casemate of railroad iron.

On 29 June 1862, Robert E. Lee had the gun pushed by a locomotive over the Richmond and York River line (later part of the Southern Railway) and used at the Battle of Savage's Station to interfere with General George McClellan's plans for siege operations against Richmond during the Union advance up the peninsula.

[10] A flatcar strengthened by additional beams covered by iron plate was able to resist recoil damage from a full charge.

The Dictator was then fired from a section of the Petersburg and City Point Railroad where moving the strengthened flatcar along a curve in the track trained the gun on different targets along the Confederate lines.

The Dictator silenced the Confederate guns on Chesterfield Heights to prevent them from enfilading the right end of the Union line.

The French arms maker Schneider offered a number of models in the late 1880s and produced a 120 mm (4.7 in) gun intended for coastal defense, selling some to the Danish government in the 1890s.

They also designed a 200 mm (7.9 in) model the Obusier de 200 "Pérou" sur affût-truck TAZ Schneider for Peru in 1910, but they were never delivered.

[13] The United Kingdom mounted a few 4.7 in (120 mm) guns on railway cars which saw action during the Siege and Relief of Ladysmith during the Second Boer War.

[14] A 9.2 inch gun was taken from the Cape Town coast defences and mounted on a rail car to support the British assault on Boer defenses at Belfast, north-east of Johannesburg, but the battle ended before it could get into action.

[18] Baldwin Locomotive Works delivered five 14"/50 caliber railway guns on trains for the United States Navy during April and May 1918.

[20] After delivery by ship, these trains were assembled in St. Nazaire in August[21] and fired a total of 782 shells during 25 days on the Western Front at ranges between 27 and 36 kilometres (30,000 and 39,000 yd).

The railway carriages could elevate the guns to 43 degrees, but elevations over 15 degrees required excavation of a pit with room for the gun to recoil and structural steel shoring foundations to prevent caving of the pit sides from recoil forces absorbed by the surrounding soil.

Some were later stationed through World War II in special coast defense installations at San Pedro, California, (near Los Angeles) and in the Panama Canal Zone where they could be shifted from one ocean to the other in less than a day.

Improved carriages were designed to allow their transportation to several fixed firing emplacements including concrete foundations where the railway trucks were withdrawn so the gun could be rapidly traversed (swiveled horizontally) to engage moving ship targets.

[24] After the American entry into World War I on 6 April 1917, the U.S. Army recognized the need to adopt railway artillery for use on the Western Front.

Due to low production and shipping priorities, the Army's railway gun contribution on the Western Front consisted of four U.S. Coast Artillery regiments armed with French-made weapons.

To shorten a long story, none of these weapons were shipped to France except three 8-inch guns, as few of any type were completed before the Armistice.

[18] Both Nazi Germany and Great Britain deployed railway guns that were capable of firing across the English Channel in the areas around Dover and Calais.

The 18-inch howitzer "Boche Buster" was sited on the Elham Valley Railway, between Bridge, Kent, and Lyminge, and was intended for coastal defense against invasion.