Raj of Sarawak

His nephew, Charles Brooke, succeeded James and normalised the situation by improving the economy, reducing government debt and establishing public infrastructure.

With proper economic planning and stability, Sarawak prospered and emerged as one of the world's major producers of black pepper, in addition to oil and the introduction of rubber plantations.

[13] By July 1839, he reached Singapore and came across some British sailors who had been shipwrecked and helped by Pengiran Raja Muda Hashim, the uncle of Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin II of Brunei.

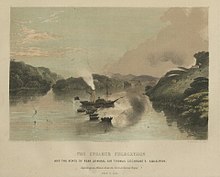

[9][19][20] He sailed to the western coast of the island the following month, and on 14 August 1839 berthed his schooner on the banks of the Sarawak River and met Hashim to deliver the message.

[18][21][22] Mahkota had earlier been dispatched by the Sultan to monopolise the antimony in the area; which as a result directly affected the income of the local Malays there amid growing frustration from the indigenous Land Dayak, who had been forced to work in the mines for about 10 years.

[23][24] It has also been alleged that the rebellion against Brunei was aided by the neighbouring Sultanate of Sambas and the government of the Dutch East Indies, who wanted to establish economic rights over the antimony.

[35] Brooke left the next day in the Royalist for Singapore, only to return to Sarawak in May 1841 with a second boat: the Swift, filled with British manufactured goods to trade with Muda Hashim.

[38] Brooke issued new laws for the territory banning slavery, headhunting and piracy;[39] and by July 1842, his appointment was confirmed by Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin II.

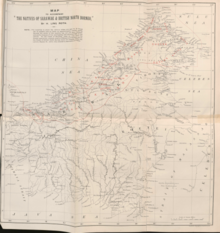

Keppel and Brooke's native forces once again overwhelmed all opposition in Patusan and the Undop, but were ambushed by the Sea Dayak on the river Skrang at Karangan Peris, resulting in the death of Datu Patinggi Ali.

Shortly after this punitive expedition Brooke heard that Mahkota, the former administrator of the Kuching area, had taken shelter at the Lingga, and managed to capture him and send him back to Brunei.

[48][49] Badruddin accused Yusof of being involved in the slave trade due to his close relations with a notable pirate leader –Sharif Usman– in Marudu Bay and the Sultanate of Sulu.

[48][49] Hashim managed to establish a rightful position in Brunei Town to become the next sultan after successfully defeating the pirates led by Yusof who fled to Kimanis in northern Borneo, where he was executed.

He prevailed on the Sultan to order the execution of Hashim,[49] whose presence had become unwelcome to the royal family, especially due to his close ties with Brooke that were favourable to English policy.

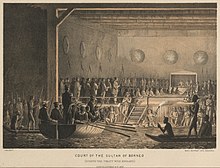

[54] On 6 July 1846, Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin II complained through a letter about the discourtesy of HMS Hazard and invited Cochrane to ascend the capital of Brunei with two boats.

[56] Through his confession, the Sultan recognised Brooke's authority over Sarawak and mining rights throughout the territory without requiring him to pay any tribute as well granting the island of Labuan to the British.

[56] Brooke departed Brunei and left Mumin in charge together with Mundy to keep the Sultan in line until the British government made a final decision to acquire the island.

[60] Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddin II died in 1852 and he was succeeded by Mumin, which already proved a success in Brooke's efforts to establish a pro-British government in Brunei.

[62][63] Three major rebellions led by Rentap (1853),[64] Liu Shan Bang (1857)[65][66] and Syarif Masahor (1860)[67] shook the Rajah's administration which, together with the stagnant economic conditions at the time, caused Brooke to be plagued by debt.

[77][78] Under Charles' administration, Sarawak's economy grew rapidly, especially later on with the discovery of oil, introduction of rubber, and the construction of public infrastructure as his main priorities to stabilise the economic situation and reduce government debts.

[91] As Sarawak had a significant number of oil refineries in Miri and Lutong, the British feared that these supplies would fall to Japanese control, and thus instructed the infantry to carry out a scorched earth policy.

Vyner returned to administer Sarawak but decided to cede it to the British government as a Crown colony on 1 July 1946 due to a lack of resources to finance reconstruction.

[104] A Resident's job was to establish law and order, convene courts to settle disputes, punish crimes, be accessible at all times to the natives, and "gain the confidence of the chiefs of the wilder tribes and to lead them to accept the Sarawak flag and the benefits of the Rajah's government".

The kingdom's authorities conducted repeated raids on Sea Dayak villages and, facing a major rebellion, ultimately forced them to practice horticulture and abandon headhunting.

In contrast to Dutch East Indies's forced cultivation system (cultuurstelsel), the indigenous people of Sarawak paid only a small amount of door tax and land rent.

[123] In 1869, by which time total trade had reached $3,262,500,[86] the Charles Brooke invited Chinese black pepper and gambier growers from Singapore to cultivate their crops in Sarawak.

[136] Land transport in Sarawak was poorly developed owing to the swampy environment around rivers downstream, while dense jungles presented significant challenges to road construction inland.

[139] Subsequent construction of a road running parallel to the railway led to substantial losses, however, and its operations were limited to transportation of rocks from Seventh Mile (now Kota Sentosa) to Kuching.

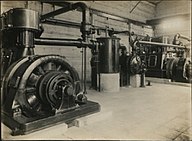

[138][140][141] In 1894, while plans for electric street lightning were being drawn up in Penang and Kuala Lumpur on the Malay Peninsula, Rajah Charles Brooke refused to adopt this new technology because of his dislike of "new-fangled things".

[152] In 1915, Dr Ledingham Christie, surgeon to Borneo Company Limited, conducted a study regarding latent dysentery and parasitism amongst the Malay population staying near the Sarawak River.

In 1902, another cholera pandemic occurred with 1,500 deaths, at a time when an expeditionary force was organised by the Brookes to punish the Dayaks living in the rural areas of the Simanggang District.