Ralph L. Brinster

Ralph Lawrence Brinster[2] (born March 10, 1932) is an American geneticist, National Medal of Science laureate, and Richard King Mellon Professor of Reproductive Physiology at the School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania.

[4][5][6] He is known throughout the scientific community for his revolutionary research in early embryo development, embryonic-cell differentiation, mechanisms of gene control, and stem cell biology.

Germline cells are at the foundation of species continuity and are responsible for propagation of individuals of varying genetic content that is critical for evolutionary competition.

Purposeful germline modification by man began about 10,000 years ago in the fertile crescent of southwest Asia with domestication of plants and animals, giving rise to agriculture and modern civilization.

The initial concept of domesticating wild species may be viewed as the first of four critical advances in man’s intervention in evolutionary germline modification and is considered by many as representing the beginning of modern human history.

The subsequent realization that selecting and breeding desirable phenotypes would lead to valuable alterations in domesticated species symbolizes the second advance.

The identification and characterization of hereditary elements, which began with the studies of Mendel and continues today with the sequencing of genomes, represents the third significant development.

Thus, the generation of transgenic animals is an extraordinary, creative development in man’s historical interaction with other species and of enormous importance in biology and medicine (see NICHD 2003 Hall of Honor and 2012 Colloquium External links below).

[5][6] His research has provided the experimental foundation for progress in germline genetic modification in a range of species, which has generated a revolution in biology, medicine, and agriculture.

[10][9] Brinster used the foundation of his culture and manipulation strategies to study techniques to alter the genetic makeup of developing embryos and their germ cells.

In the early 1970s, he injected stem cells into embryos (blastocysts) in a series of imaginative experiments which were of enormous importance and changed the way scientists thought about the possibility of modifying genes in the germline.

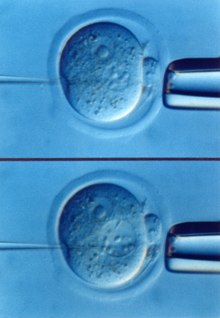

[4][6][14][15] Direct injection of fertilized mouse eggs, pioneered by Brinster, was the first approach to achieve routine experimental germline modification and served as the basis for all subsequent techniques (Fig.

[14][15][16] Transgenic mice are now used every day in thousands of laboratories around the world to investigate everything from cancer biology and cardiovascular disease to hair loss and abnormal behavior.

Their experiments, for the first time, showed that new genes could be introduced into the mammalian germline with the potential to increase disease resistance, enhance growth, and produce vital proteins like blood-clotting factors needed by hemophiliacs.

Perhaps their best known experiment was in generating the “Giant/Super Mouse”, which catalyzed interest within the scientific community and in the general public about the enormous potential of the transgenic technology being developed and is credited with the initiation of the genetic revolution in biology, medicine and agriculture (Fig.

The egg culture and injection techniques developed by Brinster serve as the basis for the CRISPR/Cas9 system of genetic modification currently used for all types of gene changes in all species.

In short, Brinster's egg injection technique was the first used to produce transgenic animals and is now the major method for making all genetic alterations in all species.

[21] Currently, scientists are extending spermatogonial stem cell culture and transplantation to prepubertal boys being treated for cancer to preserve their fertility (Fig.

"In 2003, Brinster was awarded the Wolf Prize in Medicine and was cited for “development of procedures to manipulate mouse ova and embryos, which has enabled transgenesis and its applications in mice.

Most recently, Brinster was awarded the 2010 National Medal of Science, the highest accolade bestowed by the United States government on scientists and engineers, from President Barack Obama for his seminal contributions to germline genetic modification.

Since the award was established in 1962, Brinster was the first veterinarian in the United States and the eighth scientist from the University of Pennsylvania to win the National Medal of Science.

The widely acclaimed Zadie Smith novel "White Teeth" features prominently a genetically modified mouse "Futuremouse", based loosely on the transgenic experiments of Palmiter and Brinster in the 1980s.