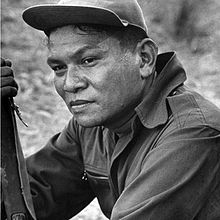

Ramon Magsaysay

An automobile mechanic by profession, Magsaysay was appointed military governor of Zambales after his outstanding service as a guerrilla leader during the Pacific War.

He then served two terms as Liberal Party congressman for Zambales's at-large district before being appointed Secretary of National Defense by President Elpidio Quirino.

For three years, Magsaysay operated under Col. Frank Merrill's famed guerrilla outfit and saw action at Sawang, San Marcelino, Zambales, first as a supply officer codenamed Chow and later as commander of a 10,000-strong force.

[5] Magsaysay was among those instrumental in clearing the Zambales coast of the Japanese prior to the landing of American forces together with the Philippine Commonwealth troops on January 29, 1945.

This success was due in part to the unconventional methods he took up from a former advertising expert and CIA agent, Colonel Edward Lansdale.

In the counterinsurgency the two utilized deployed soldiers distributing relief goods and other forms of aid to outlying, provincial communities.

Prior to Magsaysay's appointment as Defense Secretary, rural citizens perceived the Philippine Army with apathy and distrust.

He visited New York, Washington, D.C. (with a medical check-up at Walter Reed Hospital) and Mexico City, where he spoke at the Annual Convention of Lions International.

When news reached Magsaysay that his political ally Moises Padilla was being tortured by men of provincial governor Rafael Lacson, he rushed to Negros Occidental, but was too late.

He was then informed that Padilla's body was drenched in blood, pierced by fourteen bullets, and was positioned on a police bench in the town plaza.

[12] Magsaysay himself carried Padilla's corpse with his bare hands and delivered it to the morgue, and the next day, news clips showed pictures of him doing so.

Headed by soft-spoken, but active and tireless, Manuel Manahan, this committee would come to hear nearly 60,000 complaints in a year, of which more than 30,000 would be settled by direct action and a little more than 25,000 would be referred to government agencies for appropriate follow-up.

This new entity, composed of youthful personnel, all loyal to the President, proved to be a highly successful morale booster restoring the people's confidence in their own government.

[2] To amplify and stabilize the functions of the Economic Development Corps (EDCOR), President Magsaysay worked[2] for the establishment of the National Resettlement and Rehabilitation Administration (NARRA).

[2] Finally, vast irrigation projects, as well as enhancement of the Ambuklao Power plant and other similar ones, went a long way towards bringing to reality the rural improvement program advocated by President Magsaysay.

Force X employed psychological warfare through combat intelligence and infiltration that relied on secrecy in planning, training, and execution of attack.

The possibility that a communist state can influence or cause other countries to adopt the same system of government is called the domino theory.

[26] The SEATO agreement have proved to be unpopular among the Philippines' Asian neighbors, having its original members were the U.S., France, the U.K., Australia, Pakistan and New Zealand, with the U.S. as its driving force.

[27]: 91-94 Taking the advantage of the presence of U.S. Secretary John Foster Dulles in Manila to attend the SEATO Conference, the Philippine government took steps to broach with him the establishment of a Joint Defense Council.

The culmination of a series of meetings to promote Afro-Asian economic and cultural cooperation and to oppose colonialism or neocolonialism by either the United States or the Soviet Union in the Cold War, or any other imperialistic nations, the Asian–African Conference was held in Bandung, Indonesia in April 1955, upon invitation extended by the Prime Ministers of India, Pakistan, Burma, Ceylon, and Indonesia.

[2] At the very outset indications were to the effect that the conference would promote the cause of neutralism as a third position in the current Cold War between the capitalist bloc and the communist group.

Ambassador Rómulo delivered a stinging, eloquent retort that prompted Prime Minister Nehru to publicly apologize to the Philippine delegation.

Instead, participating countries viewed that colonialism, racialism, cultural suppression, discrimination, and nuclear weapons as regional threats.

Solutions offered by the conference for these threats were less ideological, which namely includes:[27]: 93 (1) respect for human rights; (2) respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity of all nations; (3) recognition of the equality of all races and of all nations; (4) non-interference in the internal affairs of another country; (5) respect for the right of each nation to defend itself singly or collectively, in accordance with the UN Charter; (6) refraining from acts of threats or aggression or the use of force against another country; (7) promotion of mutual interests and cooperation; and (8) respect for justice and international obligations.Following the reservations made by Ambassador Rómulo, on the Philippines' behalf, upon signing the Japanese Peace Treaty in San Francisco on September 8, 1951, for several years of series of negotiations were conducted by the Philippine government and that of Japan.

In the face of adamant claims of the Japanese government that it found impossible to meet the demand for the payment of eight billion dollars by the way of reparations, President Magsaysay, during a so-called "cooling off"[2] period, sent a Philippine Reparations Survey Committee, headed by Finance Secretary Jaime Hernandez, to Japan for an "on the spot" study of that country's possibilities.

[2] When the Committee reported that Japan was in a position to pay, Ambassador Felino Neri, appointed chief negotiator, went to Tokyo.

[2] On August 12, 1955, President Magsaysay informed the Japanese government, through Prime Minister Ichiro Hatoyama, that the Philippines accepted the Neri-Takazaki agreement.

The official Reparations agreement between the two government was finally signed at Malacañang Palace on May 9, 1956, thus bringing to a rather satisfactory conclusion this long drawn controversy between the two countries.

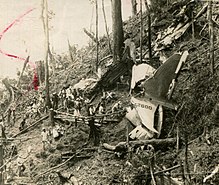

After his death, vice-president Carlos P. Garcia was inducted into the presidency on March 18, 1957, to complete the last eight months of Magsaysay's term.

Trade and industry flourished, the Philippine military was at its prime, and the country gained international recognition in sports, culture, and foreign affairs.