Ramsey's theorem

In combinatorics, Ramsey's theorem, in one of its graph-theoretic forms, states that one will find monochromatic cliques in any edge labelling (with colours) of a sufficiently large complete graph.

The task of proving that R(3, 3) ≤ 6 was one of the problems of William Lowell Putnam Mathematical Competition in 1953, as well as in the Hungarian Math Olympiad in 1947.

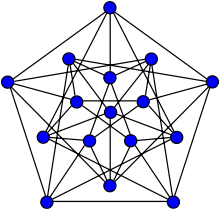

Since every vertex, except for v itself, is in one of the red, green or blue neighbourhoods of v, the entire complete graph can have at most 1 + 5 + 5 + 5 = 16 vertices.

Assume without loss of generality that d1 is even, and that M and N are the vertices incident to vertex 1 in the blue and red subgraphs, respectively.

Erdős asks us to imagine an alien force, vastly more powerful than us, landing on Earth and demanding the value of R(5, 5) or they will destroy our planet.

[9] The exact value of R(5, 5) is unknown, although it is known to lie between 43 (Geoffrey Exoo (1989)[10]) and 46 (Angeltveit and McKay (2024)[11]), inclusive.

The best known lower and upper bounds for diagonal Ramsey numbers are due to Spencer and Conlon, respectively; a 2023 preprint by Campos, Griffiths, Morris and Sahasrabudhe claims to have made exponential progress using an algorithmic construction relying on a graph structure called a "book",[17][18] improving the upper bound to with

For the off-diagonal Ramsey numbers R(3, t), it is known that they are of order t2/log t; this may be stated equivalently as saying that the smallest possible independence number in an n-vertex triangle-free graph is The upper bound for R(3, t) is given by Ajtai, Komlós, and Szemerédi,[20] the lower bound was obtained originally by Kim,[21] and the implicit constant was improved independently by Fiz Pontiveros, Griffiths and Morris,[22] and Bohman and Keevash,[23] by analysing the triangle-free process.

up to logarithmic factors, and settling a question of Erdős, who offered 250 dollars for a proof that the lower limit has form

[29] This verification was achieved using a combination of Boolean satisfiability (SAT) solving and computer algebra systems (CAS).

was completed in approximately 8 hours of wall clock time, producing a total proof size of 5.8 GiB.

was significantly more computationally intensive, requiring 26 hours of wall clock time and generating 289 GiB of proof data.

[31] The original proof, developed by McKay and Radziszowski in 1995, combined high-level mathematical arguments with computational steps and used multiple independent implementations to reduce the possibility of programming errors.

This new formal proof was carried out using the HOL4 interactive theorem prover, limiting the potential for errors to the HOL4 kernel.

Rather than directly verifying the original algorithms, the authors utilized HOL4's interface to the MiniSat SAT solver to formally prove key gluing lemmas.

The qualitative statement of the theorem in the next section was first proven independently by Erdős, Hajnal and Pósa, Deuber and Rödl in the 1970s.

[32][33][34] However, the original proofs gave terrible bounds (e.g. towers of twos) on the induced Ramsey numbers.

In 1974, Paul Erdős conjectured that there exists a constant c such that every graph H on k vertices satisfies rind(H) ≤ 2ck.

[35] If this conjecture is true, it would be optimal up to the constant c because the complete graph achieves a lower bound of this form (in fact, it's the same as Ramsey numbers).

It was not until 1998 when a major breakthrough was achieved by Kohayakawa, Prömel and Rödl, who proved the first almost-exponential bound of rind(H) ≤ 2ck(log k)2 for some constant c. Their approach was to consider a suitable random graph constructed on projective planes and show that it has the desired properties with nonzero probability.

In 2008, Fox and Sudakov provided an explicit construction for induced Ramsey numbers with the same bound.

Currently, Erdős's conjecture that rind(H) ≤ 2ck remains open and is one of the important problems in extremal graph theory.

Note that this is in contrast to the usual Ramsey numbers, where the Burr–Erdős conjecture (now proven) tells us that r(H) is linear (since trees are 1-degenerate).

This result was first proven by Łuczak and Rödl in 1996, with d(Δ) growing as a tower of twos with height O(Δ2).

In 2013, Conlon, Fox and Zhao showed using a counting lemma for sparse pseudorandom graphs that rind(H) ≤ cn2Δ+8, where the exponent is best possible up to constant factors.

The current best known bound is due to Fox and Sudakov, which achieves rind(H;q) ≤ 2ck3, where k is the number of vertices of H and c is a constant depending only on q.

Using the hypergraph container method, Conlon, Dellamonica, La Fleur, Rödl and Schacht were able to show that for d ≥ 3, q ≥ 2, rind(H;q) ≤ td(ck) for some constant c depending on only d and q.

[46] It is possible to deduce the finite Ramsey theorem from the infinite version by a proof by contradiction.

[49] It is also possible to define Ramsey numbers for directed graphs; these were introduced by P. Erdős and L. Moser (1964).

for all finite n and k. Wacław Sierpiński showed that the Ramsey theorem does not extend to graphs of size

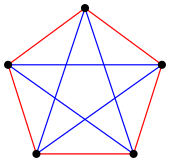

Due to the pigeonhole principle, there are at least 3 edges of the same colour (dashed purple) from an arbitrary vertex v . Calling 3 of the vertices terminating these edges x , y and z , if the edge xy , yz or zx (solid black) had this colour, it would complete the triangle with v . But if not, each must be oppositely coloured, completing triangle xyz of that colour.