Noise (electronics)

While noise is generally unwanted, it can serve a useful purpose in some applications, such as random number generation or dither.

Thermal noise is approximately white, meaning that its power spectral density is nearly equal throughout the frequency spectrum.

Vacuum tubes exhibit shot noise because the electrons randomly leave the cathode and arrive at the anode (plate).

A tube may not exhibit the full shot noise effect: the presence of a space charge tends to smooth out the arrival times (and thus reduce the randomness of the current).

Pentodes and screen-grid tetrodes exhibit more noise than triodes because the cathode current splits randomly between the screen grid and the anode.

Shot noise has been demonstrated in mesoscopic resistors when the size of the resistive element becomes shorter than the electron–phonon scattering length.

Burst noise consists of sudden step-like transitions between two or more discrete voltage or current levels, as high as several hundred microvolts, at random and unpredictable times.

Thermal noise can be reduced by cooling of circuits - this is typically only employed in high accuracy high-value applications such as radio telescopes.

In a digital communications system, a certain Eb/N0 (normalized signal-to-noise ratio) would result in a certain bit error rate.

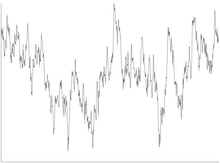

Noise is a random process, characterized by stochastic properties such as its variance, distribution, and spectral density.

The spectral distribution of noise can vary with frequency, so its power density is measured in watts per hertz (W/Hz).

Since the power in a resistive element is proportional to the square of the voltage across it, noise voltage (density) can be described by taking the square root of the noise power density, resulting in volts per root hertz (

Integrated circuit devices, such as operational amplifiers commonly quote equivalent input noise level in these terms (at room temperature).