Firmament

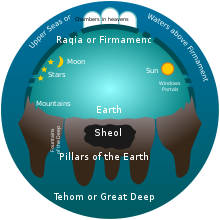

In ancient near eastern cosmology, the firmament means a celestial barrier that separates the heavenly waters above from the Earth below.

[1] In biblical cosmology, the firmament (Hebrew: רָקִ֫יעַ rāqīaʿ) is the vast solid dome created by God during the Genesis creation narrative to separate the primal sea into upper and lower portions so that the dry land could appear.

[2][3] The concept was adopted into the subsequent Classical and Medieval models of heavenly spheres, but was dropped with advances in astronomy in the 16th and 17th centuries.

The same word is found in French and German Bible translations, all from Latin firmamentum (a firm object), used in the Vulgate (4th century).

[5][6] The Hebrew lexicographers Brown, Driver and Briggs gloss the noun with "extended surface, (solid) expanse (as if beaten out)" and distinguish two main uses: 1.

Between these two main sources, there is a fundamental agreement in the cosmological models pronounced: this included a flat and likely disk-shaped world with a solid firmament.

[13][14] In Egyptian texts particularly, these gates also served as conduits between the earthly and heavenly realms for which righteous people could ascend.

[19] The fourth model was a flat (or slightly convex) celestial plane which, depending on the text, was thought to be supported in various ways: by pillars, staves, scepters, or mountains at the extreme ends of the Earth.

[27] In the Hexaemeron of Basil of Caesarea the firmament is depicted as spherical or domed with a flat underside that formed a pocket or membrane in which the waters were held.

In De Genesi ad litteram (perhaps his least studied work) Augustine wrote: "only God knows how and why [the waters] are there, but we cannot deny the authority of Holy Scripture which is greater than our understanding".

[36] A distinctive collection of ideas about the cosmos were drawn up and recorded in the rabbinic literature, though the conception is rooted deeply in the tradition of near eastern cosmology recorded in Hebrew, Akkadian, and Sumerian sources, combined with some additional influences in the newer Greek ideas about the structure of the cosmos and the heavens in particular.

[37] The rabbis viewed the heavens to be a solid object spread over the Earth, which was described with the biblical Hebrew word for the firmament, raki’a.

This is somewhat similar to a view attributed to Anaximander, whereby the firmament is made of a mixture of hot and cold (or fire and moisture).

[41] A range of additional discussions in rabbinic texts surrounding the firmament included those on the upper waters,[42] the movements of the heavenly bodies and the phenomena of precipitation,[43] and more.

[46] In the Testament of Solomon, the heavens are conceived in a tripartite structure and demons are portrayed as being capable of flying up to and past the firmament in order to eavesdrop on the decisions of God.

[53] In addition, there are seven heavens or firmaments[54][55] and they were made from smoke during the creation week, resembling the view of Basil of Caesarea.

[56] The model established by Aristotle became the dominant model in the Classical and Medieval world-view, and even when Copernicus placed the Sun at the center of the system he included an outer sphere that held the stars (and by having the earth rotate daily on its axis it allowed the firmament to be completely stationary).

Tycho Brahe's studies of the nova of 1572 and the Comet of 1577 were the first major challenges to the idea that orbs existed as solid, incorruptible, material objects,[57] and in 1584 Giordano Bruno proposed a cosmology without a firmament: an infinite universe in which the stars are actually suns with their own planetary systems.

[58] After Galileo began using a telescope to examine the sky it became harder to argue that the heavens were perfect, as Aristotelian philosophy suggested, and by 1630 the concept of solid orbs was no longer dominant.