Rashid al-Din Hamadani

He was commissioned by Ghazan to write the Jāmiʿ al-Tawārīkh, now considered the most important single source for the history of the Ilkhanate period and the Mongol Empire.

[2] Historian Morris Rossabi calls Rashid al-Din "arguably the most distinguished figure in Persia during Mongolian rule".

He served as vizier and physician under the Ilkhans Ghazan and Öljaitü before falling to court intrigues during the reign of Abu Sa'id Bahadur Khan, whose ministers had him killed at the age of seventy.

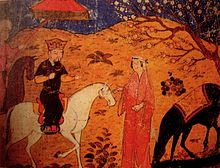

Portions of the Jāmiʿ al-Tawārīkh survive in lavishly illustrated manuscripts, believed to have been produced during Rashid's lifetime and perhaps under his direct supervision at the Rab'-e Rashidi workshop.

[6] The most important historiographic legacy of the Jāmiʿ al-Tawārīkh may be its documentation of the cultural mixing and ensuing dynamism that led to the greatness of the subsequent Timurid, Safavid Iran, Qajar, and Ottoman Empires, many aspects of which were transmitted to Europe and influenced the Renaissance.

The text describes the different peoples with whom the Mongols came into contact and is one of the first attempts to transcend a single cultural perspective and to treat history on a universal scale.

One of the volumes of the Jāmiʿ al-Tawārīkh deals with an extensive History of the Franks (1305/1306), possibly based on information from Europeans working under the Ilkhanids such as Isol the Pisan or the Dominican friars, which is a generally consistent description with many details on Europe's political organization, the use of mappae mundi by Italian mariners and regnal chronologies derived from the chronicle of Martin of Opava (d.

In order to facilitate this, he set aside a fund to pay for the annual transcription of two complete manuscripts of his works, one in Arabic and one in Persian.

The printing process used at the workshop has been described by Rashid al-Din, and bears very strong resemblance to the processes used in the large printing ventures in China under Feng Dao (932–953): [W]hen any book was desired, a copy was made by a skillful calligrapher on tablets and carefully corrected by proof-readers whose names were inscribed on the back of the tablets.

When completed, the tablets were placed in sealed bags to be kept by reliable persons, and if anyone wanted a copy of the book, he paid the charges fixed by the government.

Abu al-Qasim Kashani (d. 1324), who wrote the most important extant contemporary source on Öljaitü, maintained that he himself was the true author of the Jāmiʿ al-Tawārīkh, "for which Rashid al-Din had stolen not only the credit but also the very considerable financial rewards.

"[2] According to Encyclopædia Iranica, "While there is little reason to doubt Rashid al-Din’s overall authorship of the Jāmiʿ al-Tawārīkh, the work has generally been considered a collective effort, partly carried out by research assistants.

His letters intensely criticize the sub-national Mongol amirs (whom he referred to as "Turks"), who made the centralized administration of the Ilkhan difficult.