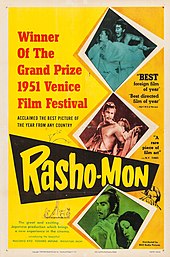

Rashomon

Starring Toshiro Mifune, Machiko Kyō, Masayuki Mori, and Takashi Shimura, it follows various people who describe how a samurai was murdered in a forest.

Every element is largely identical, from the murdered samurai speaking through a Shinto psychic to the bandit in the forest, the monk, the assault of the wife, and the dishonest retelling of the events in which everyone shows their ideal self by lying.

When creating the film's visual style, Kurosawa and cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa experimented with various methods such as pointing the camera at the sun, which was considered taboo.

Rashomon premiered at the Imperial Theatre on August 25, 1950, and was distributed throughout Japan the following day, to moderate commercial success, becoming Daiei's fourth highest-grossing film of 1950.

It pioneered the Rashomon effect, a plot device that involves various characters providing subjective, alternative, and contradictory versions of the same incident.

In Heian-era Kyoto, a woodcutter and a priest, taking shelter from a downpour under the Rashōmon city gate, recount a story of a recent assault and murder.

[10] Reports on the budget in Western currency vary: The Guinness Book of Movie Facts and Feats cited it as $40,000,[11] The New York Times and Stuart Galbraith IV noted a reputed $140,000 figure,[12][13] and a handful of other sources have claimed that it cost as high as $250,000.

He added that it "seems highly unlikely given that the 125 million yen, approximately $350,000, that Kurosawa subsequently spent on Seven Samurai four years later made this film by far the most expensive domestic production up to this point".

The pair regularly commenced writing their respective films at 9:00 a.m. and would give feedback on each other's work after each completed roughly twenty pages.

[6] Kurosawa had initially wanted the cast of eight to consist entirely of previous collaborators, specifically counseling Toshiro Mifune and Takashi Shimura.

He also suggested that Setsuko Hara—who had played the lead in No Regrets for Our Youth (1946)—portray the wife, but she was not cast since her brother-in-law, filmmaker Hisatora Kumagai, was against it; Hara would subsequently appear in Kurosawa's next film, The Idiot (1951).

[16] The cinematographer, Kazuo Miyagawa, contributed numerous ideas, technical skill and expertise in support for what would be an experimental and influential approach to cinematography.

[citation needed] Professor Keiko I. McDonald opposes Sato's idea in her essay "The Dialectic of Light and Darkness in Kurosawa's Rashomon."

Due to its emphasis on the subjectivity of truth and the uncertainty of factual accuracy, Rashomon has been read by some as an allegory of the defeat of Japan at the end of World War II.

Moreover, Kurosawa and other filmmakers were not allowed to make jidaigeki during the early part of the occupation, so setting a film in the distant past was a way to reassert domestic control over cinema.

It was an instant box office success, leading several theaters to continue to play it for two or three weeks rather than a Japanese film's regular one-week theatrical run.

Japanese film companies had no interest in international festivals and were reluctant to submit the movie because paying for printing and creating subtitles was considered a waste of money.

But once it had been screened, Rashomon drew an overwhelmingly positive response from festival audiences, praising its originality and techniques while making many question the nature of truth.

[41] The Criterion Collection later issued a Blu-ray and DVD edition of the film based on the 2008 restoration, accompanied by a number of additional features.

[48][49] Ed Sullivan gave the film a positive review in Hollywood Citizen-News, calling it "an exciting evening, because the direction, the photography and the performances will jar open your eyes."

He praised Akutagawa's original plot, Kurosawa's impactful direction and screenplay, Mifune's "magnificent" villainous performance, and Miyagawa's "spellbinding" cinematography that achieves "visual dimensions that I've never seen in Hollywood photography" such as being "shot through a relentless rainstorm that heightens the mood of the somber drama.

[4][53][54] Assistant director Tokuzō Tanaka said that Nagata broke the abrupt few minutes of silence following its preview screening at the company's headquarters in Kyōbashi by saying "I don't really get it, but it's a noble photograph".

He reflected being disgusted by the company's president taking credit for the film's achievements: "Watching that television interview, I had the feeling that I was back in the world of Rashomon all over again.

[47] Among these were Kōzaburō Yoshimura's The Tale of Genji (1951), Teinosuke Kinugasa's Dedication of the Great Buddha (1952) and Gate of Hell (1953), Kenji Mizoguchi's Ugetsu (1953), and Keigo Kimura's The Princess Sen (1954), all of which received screenings overseas.

[63][64][f] Based on another story by Akutagawa, composed by Hayasaka, and starring Kyō, Mori, Shimura, Katō, and Honma, the film has been described as an inferior imitator of Rashomon and has since faded into obscurity.

[65][47] Mifune was also initially going to appear in Beauty and the Thief as suggested by a photograph of him taken by Werner Bischof during production in 1951 when the film was allegedly titled "Hokkaido".

[40] It has since been cited as an inspiration for numerous films from around the world, including Andha Naal (1954),[68] Valerie (1957),[69] Last Year at Marienbad (1961),[70] Yavanika (1982),[71] Quentin Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs (1992)[72] and Pulp Fiction (1994),[7] The Usual Suspects (1995),[7] Courage Under Fire (1996),[73] Tape (2001),[7] Hero (2002),[7] and Fast X (2023).

For example, the way Kurosawa uses his camera...takes this fascinating meditation on human nature closer to the style of silent film than almost anything made after the introduction of sound.

[78][79] Examples include: In the years following its release, several publications have named Rashomon one of the greatest films of all time, and it is also cited in the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die.

The website's consensus reads: "One of legendary director Akira Kurosawa's most acclaimed films, Rashomon features an innovative narrative structure, brilliant acting, and a thoughtful exploration of reality versus perception.