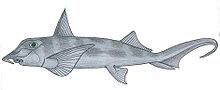

Chimaera

[4] The gill arches are condensed into a pouch-like bundle covered by a sheet of skin (an operculum), with a single gill-opening in front of the pectoral fins.

They together form a protruding, beak-like crushing and grinding mechanism, comparable to the incisor teeth of rodents and lagomorphs (hence the name "rabbit fish").

Most of each plate is formed by relatively soft osteodentin, but the active edges are supplemented by a unique hypermineralized tissue called pleromin.

Pleromin is an extremely hard enamel-like tissue, arranged into sheets or beaded rods, but it is deposited by mesenchyme-derived cells similar to those that form bone.

Exceptions include the members of the genus Callorhinchus, the rabbit fish and the spotted ratfish, which locally or periodically can be found at shallower depths.

The prepelvic tentacula are serrated hooked plates normally hidden in pouches in front of the pelvic fins, and they anchor the male to the female.

Lastly, the pelvic claspers (sexual organs shared by sharks) are fused together by a cartilaginous sheathe before splitting into a pair of flattened lobes at their tip.

Modern quotas have helped to moderate collection of these species to a sustainable level, though Callorhinchus milii (the Australian ghostshark) experienced severe overfishing in the 20th century before protections were enacted.

Neoharriotta pinnata (sicklefin chimaera) is targeted along the coast of India for its liver oil, and a recent decline of catch rates may indicate a population crash.

[13] Another threat is habitat destruction of coastal nurseries (by urban development) or deepwater reefs (by deep sea mining and trawling).

Near-shore species such as Callorhinchus milii are vulnerable to the effects of climate change: stronger storms and warmer seawater are predicted to increase egg mortality by disrupting the stable environments necessary to complete incubation.

A renewed effort to explore deep water and to undertake taxonomic analysis of specimens in museum collections led to a boom during the first decade of the 21st century in the number of new species identified.

[19] Modern chimaeras reached their highest ecological diversity during the mid-Cretaceous (Albian to Cenomanian), when they acquired a variety of different dentition types.

However, more recent studies indicate that chimaeras were likely a shallow-water group for most of their existence, and only colonized the deep ocean in the aftermath of the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event.