Mental chronometry

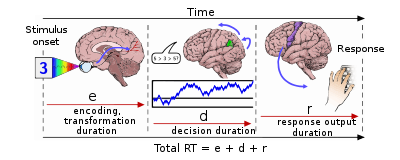

[5] Conclusions about information processing drawn from RT are often made with consideration of task experimental design, limitations in measurement technology, and mathematical modeling.

In 1820, German astronomer Friedrich Bessel applied himself to the problem of accuracy in recording stellar transits, which was typically done by using the ticking of a metronome to estimate the time at which a star passed the hairline of a telescope.

[3] Welford (1980) notes that the historical study of human reaction times were broadly concerned with five distinct classes of research problems, some of which evolved into paradigms that are still in use today.

In general, the variation in reaction times produced by manipulating sensory factors is likely more a result of differences in peripheral mechanisms than of central processes.

One of the first observations of this phenomenon comes from the research of Carl Hovland, who demonstrated with a series of candles placed at different focal distances that the effects of stimulus intensity on RT depended on previous level of adaptation.

This finding was further supported by subsequent work in the mid-1900s showing that responses were less variable when stimuli were presented near the top or bottom points of the tremor cycle.

[8] As with many sensory manipulations, such physiological response characteristics as predictors of RT operate largely outside of central processing, which differentiates these effects from those of preparation, discussed below.

Another observation first made by early chronometric research was that a "warning" sign preceding the appearance of a stimulus typically resulted in shorter reaction times.

[26][27] Whether held constant or variable, foreperiods of less than 300 ms may produce delayed RTs because processing of the warning may not have had time to complete before the stimulus arrives.

This type of delay has significant implications for the question of serially-organized central processing, a complex topic that has received much empirical attention in the century following this foundational work.

[3] The interest in the content of consciousness that typified early studies of Wundt and other structuralist psychologists largely fell out of favor with the advent of behaviorism in the 1920s.

For example, Wundt and his associate Oswald Külpe often studied reaction time by asking participants to describe the conscious process that occurred during performance on such tasks.

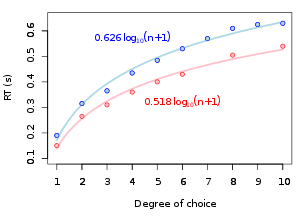

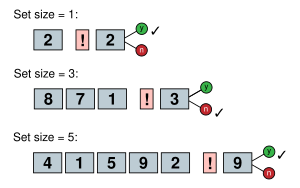

Hick showed that the individual's RT increased by a constant amount as a function of available choices, or the "uncertainty" involved in which reaction stimulus would appear next.

[3] Hick's law has interesting modern applications in marketing, where restaurant menus and web interfaces (among other things) take advantage of its principles in striving to achieve speed and ease of use for the consumer.

[42] Modern chronometric research typically uses variations on one or more of the following broad categories of reaction time task paradigms, which need not be mutually exclusive in all cases.

[49] Response criteria can also be in the form of vocalizations, such as the original version of the Stroop task, where participants are instructed to read the names of words printed in colored ink from lists.

[53] Although psycho(physio)logists have been using electroencephalographic measurements for decades, the images obtained with PET have attracted great interest from other branches of neuroscience, popularizing mental chronometry among a wider range of scientists in recent years.

The way that mental chronometry is utilized is by performing RT based tasks which show through neuroimaging the parts of the brain which are involved in the cognitive process.

[53] With the invention of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), techniques were used to measure activity through electrical event-related potentials in a study when subjects were asked to identify if a digit that was presented was above or below five.

[2] This approach to the study of mental chronometry is typically aimed at testing theory-driven hypotheses intended to explain observed relationships between measured RT and some experimentally manipulated variable of interest, which often make precisely formulated mathematical predictions.

[3] The experimental approach to mental chronometry has been used to investigate a variety of cognitive systems and functions that are common to all humans, including memory, language processing and production, attention, and aspects of visual and auditory perception.

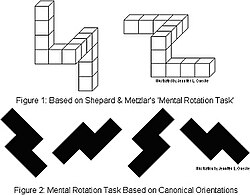

[64][65] In the late 1960s, Michael Posner developed a series of letter-matching studies to measure the mental processing time of several tasks associated with recognition of a pair of letters.

This is likely due to the fact that the majority of samples studied had been selected from universities and had unusually high mental ability scores relative to the general population.

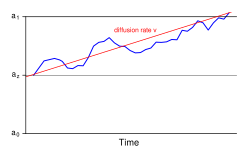

[84] Other ERP studies have found consilience with the interpretation of the g-RT relationship residing chiefly in the "decision" component of a task, wherein most of the g-related brain activity occurs following stimulation evaluation but before motor response,[85] while components involved in sensory processing change little across differences in g.[86] Although a unified theory of reaction time and intelligence has yet to achieve consensus among psychologists, diffusion modeling provides one promising theoretical model.

Under the diffusion model, this evidence accumulates by undertaking a continuous random walk between two boundaries that represent each response choice in the task.

This blend of technical vocabulary with practical examples allows the reader to gain a deeper understanding of how the diffusion model works in relation to cognitive studies.

Performance on simple and choice reaction time tasks is associated with a variety of health-related outcomes, including general, objective health composites[100] as well as specific measures like cardiorespiratory integrity.

[102] These studies generally find that faster and more accurate responses to reaction time tasks are associated with better health outcomes and longer lifespan.

While many of these studies suffer from low sample sizes (generally fewer than 200 individuals), their results are summarized below in brief along with the authors' proposed biologically plausible mechanisms.

The effect of preprocessing weakens inferences scientific evidence, it can be seen as different but rational, leading to conflicting results, false positives and negatives.