Reconstructions of Old Chinese

Although Old Chinese is known from written records beginning around 1200 BC, the logographic script provides much more indirect and partial information about the pronunciation of the language than alphabetic systems used elsewhere.

Several authors have produced reconstructions of Old Chinese phonology, beginning with the Swedish sinologist Bernhard Karlgren in the 1940s and continuing to the present day.

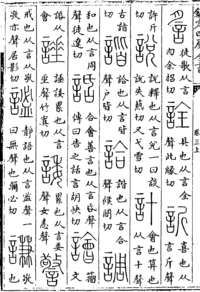

In his Qièyùn kǎo (1842), the Cantonese scholar Chen Li performed a systematic analysis of a later redaction of the Qieyun, identifying its initial and final categories, though not the sounds they represented.

Scholars have attempted to determine the phonetic content of the various distinctions by comparing them with rhyme tables from the Song dynasty, pronunciations in modern varieties and loans in Korean, Japanese and Vietnamese (the Sinoxenic materials), but many details regarding the finals are still disputed.

According to its preface, the Qieyun did not reflect a single contemporary dialect, but incorporated distinctions made in different parts of China at the time (a diasystem).

[3][4] The fact that the Qieyun system contains more distinctions than any single contemporary form of speech means that it retains additional information about the history of the language.

[5] For example, it includes 37 initials, but in the early 20th century Huang Kan observed that only 19 of them occurred with a wide range of finals, implying that the others were in some sense secondary developments.

[11] Earlier characters from oracle bones and Zhou bronze inscriptions often reveal relationships that were obscured in later forms.

This was attributed to lax rhyming practice of early poets until the late-Ming dynasty scholar Chen Di argued that a former consistency had been obscured by sound change.

[16][17] These were used in all reconstructions up to the 1980s, when Zhengzhang Shangfang, Sergei Starostin and William Baxter independently proposed a more radical splitting into more than 50 rhyme groups.

For example, the following dental initials have been identified in reconstructed proto-Min:[21][22] Other points of articulation show similar distinctions within stops and nasals.

Of particular importance are the many Buddhist transcriptions of the Eastern Han period, because the native pronunciation of the source languages, such as Sanskrit and Pali, is known in detail.

[26] By studying such glosses, the Qing philologist Qian Daxin discovered that the labio-dental and retroflex stop initials identified in the rhyme table tradition were not present in the Han period.

The earliest borrowings in both directions provide further evidence of Old Chinese sounds, though complicated by uncertainty about the reconstruction of early forms of those languages.

He also proposed a series of unaspirated voiced initials to account for other correspondences, but later workers have discarded these in favour of alternative explanations.

[47] Wang Li made extensive studies of Shijing rhymes and produced a reconstruction that, with minor variations, is still in wide use in China.

[59] In a pair of papers published in 1960, the Russian linguist Sergei Yakhontov proposed two revisions to the structure of Old Chinese that are now widely accepted.

[75] Pulleyblank also proposed an Old Chinese labial fricative *v for the few words where Karlgren had *b, as well as a voiceless counterpart *f.[76] Unlike the above ideas, these have not been adopted by later workers.

[84] The Chinese linguist Li Fang-Kuei published an important new reconstruction in 1971, synthesizing proposals of Yakhontov and Pulleyblank with ideas of his own.

Baxter did not produce a dictionary of reconstructions, but the book contains a large number of examples, including all the words occurring in rhymes in the Shijing, and his methods are described in great detail.

[87] Other additions were *z, with a limited distribution,[96] and voiceless and voiced palatals *hj and *j, which he described as "especially tentative, being based largely on scanty graphic evidence".

The evidence is limited, and consists mainly of contacts between rising tone syllables and -k finals, which could alternatively be explained as phonetic similarity.

[117] They used additional evidence, including word relationships deduced from these morphology theories, Norman's reconstruction of Proto-Min, divergent Chinese varieties such as Waxiang, early loans to other languages, and character forms in recently unearthed documents.

[124] They propose uvular initials as a second source of the Middle Chinese palatal initial in addition to *l, so that series linking Middle Chinese y- with velars or laryngeals instead of dentals are reconstructed as uvulars rather than laterals, for example[124] Baxter and Sagart concede that it is typologically unusual for a language to have as many pharyngealized consonants as nonpharyngealized ones, and suggest that this situation may have been short-lived.

[129] Rarely, the minor syllables received a separate character, explaining a few puzzling examples of 不 *pə- and 無 *mə- used in non-negative sentences.

For example, they propose nasal prefixes *N- (detransitiviser) and *m- (agentive, among other functions) as a source of the initial voicing alterations in Middle Chinese; both also have cognates in Tibeto-Burman.

Karlgren first stated the principle that words written with the same phonetic component had initials with a common point of articulation in Old Chinese.

Li Rong, in a systematic comparison of the rhyme tables with a recently discovered early edition of the Qieyun, identified seven classes of finals.

This segment also accounts for phonetic series contacts between stops and l-, retroflex initials and (in some later work) the chongniu distinction.

[203] Some words in the Shijing 質 zhì and 物 wù rhyme groups have Middle Chinese reflexes in the departing tone, but otherwise parallel to those with dental finals.