Red-figure pottery

The outlines of the intended figures were drawn either with a blunt scraper, leaving a slight groove, or with charcoal, which would disappear entirely during firing.

The ongoing trend to depict heroes and deities naked and of youthful age also made it harder to distinguish the sexes through garments or hairstyles.

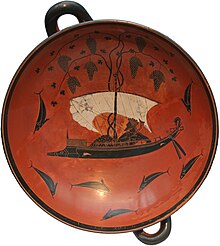

[1] Black-figure vase painting had been developed in Corinth in the 7th century BC and quickly became the dominant style of pottery decoration throughout the Greek world and beyond.

Attic artists developed the style to an unprecedented quality, reaching the apex of their creative possibilities in the second third of the 6th century BC.

Although there is no indication that the painters understood themselves as a group in the way that modern scholarship does, there were some connections and mutual influences, perhaps in an atmosphere of friendly competition and encouragement.

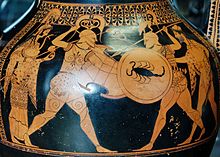

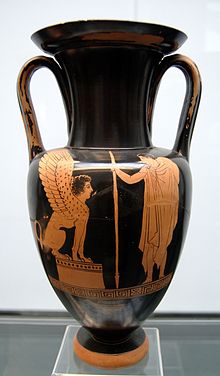

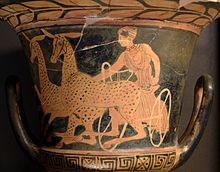

[3] One of the key features of this most successful Attic vase painting style is the mastery of perspective foreshortening, allowing a much more naturalistic depiction of figures and actions.

Since Greek wall painting is almost entirely lost today, its reflection on vases constitutes one of the few, albeit modest, sources of information on that genre of art.

Over time, there is a marked "softening": The male body, heretofore defined by the depiction of muscles, gradually lost that key feature.

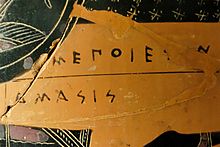

In contrast, the signature of the potter, ἐποίησεν (epoíesen, has made) has survived on more than twice as many, namely about 100, pots (both numbers refer to the totality of Attic figural vase painting).

A changing, apparently increasingly negative, attitude to artisans led to a reduction of signatures, starting during the Classical period at the latest.

This division of labor appears to have developed along with the introduction of red-figure painting, since many potter-painters are known from the black-figure period (including Exekias, Nearchos and perhaps the Amasis Painter).

The increased demand for exports would have led to new structures of production, encouraging specialisation and division of labor, leading to a sometimes ambiguous distinction between painter and potter.

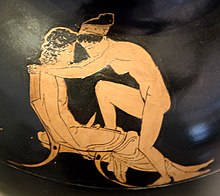

Do the frequent depictions of the symposium, a definite upper-class activity, reflect the painters' personal experience, their aspirations to attend such events, or simply the demands of the market?

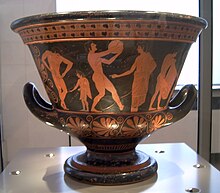

[10] A large proportion of the painted vases produced, such as psykter, krater, kalpis, stamnos, as well as kylikes and kantharoi, were made and bought to be used at symposia.

It is normally assumed that the lower social classes tended to use simple undecorated coarse wares, massive quantities of which are found in excavations.

[12] Nonetheless, multiple finds of red-figure vases, usually not of the highest quality, found in settlements, prove that such vessels were used in daily life.

It is hardly surprising that many workshops appear to have aimed their production at export markets, for example by producing vessel shapes that were more popular in the target region than in Athens.

The 4th century BC demise of Attic vase painting tellingly coincides with the very period when the Etruscans, probably the main western export market, came under increasing pressure from South Italian Greeks and the Romans.

Buyers from other cultural backgrounds, such as Etruscans or later customers in the Iberian Peninsula, would have found such depiction incomprehensible or uninteresting.

[14] At least from a modern point of view, the Southern Italian red-figure vase paintings represent the only region of production that reaches Attic standards of artistic quality.

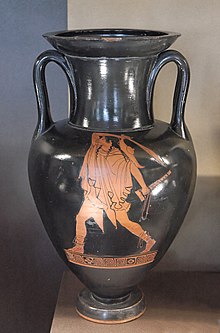

[17] The artists using the ornate style tended to favour large vessels, like volute kraters, amphorae, loutrophoroi and hydriai.

Their work is characterised by a preference for satyr figures with thyrsos, depictions of heads (normally below the handles of hydriai), decorative borders of garments, and the frequent use of additional white, red and yellow.

His successors were not fully able to maintain his quality, leading to a rapid demise, terminating with the end of Campanian vase painting around 300 BC.

[24] The themes depicted often belong to the Dionysiac cycle: thiasos and symposium scenes, satyrs, maenads, Silenos, Orestes, Electra, the gods Aphrodite and Eros, Apollo, Athena and Hermes.

At the same time, an influence by the Campanian Caivano Painter becomes notable, garments falling in a linear fashion and contourless female figures followed.

In terms of style, themes, ornamentation and vase shapes, the workshops were strongly influenced by the Attic tradition, especially by the Late Classical Meidias Painter.

The few exceptions include some workshops in Boeotia (Painter of the Great Athens Kantharos), Chalkidike, Elis, Eretria, Corinth and Laconia.

A rare pre-Classicist exception is a book of watercolours depicting figural vases, which was produced for Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc.

Famous scholars who continued the study of Attic red-figure after Beazley include John Boardman, Erika Simon and Dietrich von Bothmer.

[35] For the study of South Italian case painting, Arthur Dale Trendall's work has a similar significance to that of Beazley for Attica.