Red Summer

The Red Summer was a period in mid-1919 during which white supremacist terrorism and racial riots occurred in more than three dozen cities across the United States, and in one rural county in Arkansas.

The term "Red Summer" was coined by civil rights activist and author James Weldon Johnson, who had been employed as a field secretary by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) since 1916.

The riots and killings were extensively documented by the press, which, along with the federal government, feared socialist and communist influence on the black civil rights movement of the time following the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia.

With the mobilization of troops for World War I, and with immigration from Europe cut off, the industrial cities of the American Northeast and Midwest experienced severe labor shortages.

[5] By 1919, an estimated 500,000 African Americans had emigrated from the Southern United States to the industrial cities of the Northeast and Midwest in the first wave of the Great Migration (which continued until 1940).

Authorities viewed with alarm African-Americans' advocacy of racial equality and labor rights, and incidents involving the deaths of whites furthered fears.

[4] In a private conversation in March 1919, President Woodrow Wilson said that "the American Negro returning from abroad would be our greatest medium in conveying Bolshevism to America.

Du Bois, an official of the NAACP and editor of its monthly magazine, saw an opportunity:[12]By the God of Heaven, we are cowards and jackasses if now that the war is over, we do not marshal every ounce of our brain and brawn to fight a sterner, longer, more unbending battle against the forces of hell in our own land.In the autumn of 1919, following the violence-filled summer, George Edmund Haynes reported on the events as a prelude to an investigation by the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary.

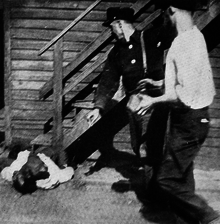

[1] In addition, Haynes reported that between January 1 and September 14, 1919, white mobs lynched at least 43 African Americans, with 16 hanged and others shot; and another 8 men were burned at the stake.

We return fighting.The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People respectfully enquires how long the Federal Government under your administration intends to tolerate anarchy in the United States?

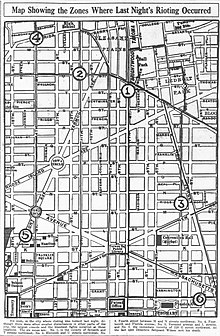

Meanwhile, the four white-owned local papers, including the Washington Post, "ginned up...weeks of hysteria",[17] fanning the violence with incendiary headlines, calling in at least one instance for a mobilization of a "clean-up" operation.

[20] The NAACP sent a telegram of protest to President Woodrow Wilson:[21] [T]he shame put upon the country by the mobs, including United States soldiers, sailors, and marines, which have assaulted innocent and unoffending negroes in the national capital.

Crowds are reported ...to have directed attacks against any passing negro.… The effect of such riots in the national capital upon race antagonism will be to increase bitterness and danger of outbreaks elsewhere.

Chicago police refused to take action against the attackers, and young black men responded with violence, which lasted for 13 days, with the white mobs led by the ethnic Irish.

Their telegram read: "The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People respectfully enquires how long the Federal Government under your administration intends to tolerate anarchy in the United States?

Once the mayor and governor appealed for help, the federal government sent U.S. Army troops from nearby forts, who were commanded by Major General Leonard Wood, a friend of Theodore Roosevelt, and a leading candidate for the Republican nomination for president in 1920.

"[31] The report generated such headlines as the following in the Dallas Morning News: "Negroes Seized in Arkansas Riots Confess to Widespread Plot; Planned Massacre of Whites Today."

The fact that white men had also been lynched in the North, he argued, demonstrated the national nature of the overall problem: "It is idle to suppose that murder can be confined to one section of the country or to one race.

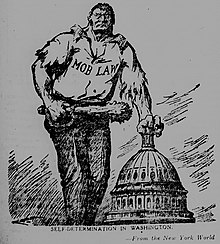

Disregard of law and legal process will inevitably lead to more and more frequent clashes and bloody encounters between white men and negroes and a condition of potential race war in many cities of the United States.

Unchecked mob violence creates hatred and intolerance, making impossible free and dispassionate discussion not only of race problems, but questions on which races and sections differ.The Joint Legislative Committee to Investigate Seditious Activities, popularly known as the Lusk Committee, was formed in 1919 by the New York State Legislature to investigate individuals and organizations in New York State suspected of sedition.

The committee was chaired by freshman State Senator Clayton R. Lusk of Cortland County, who had a background in business and conservative political values, referring to radicals as "alien enemies.

"[45] He supported that claim with copies of Negro publications that called for alliances with leftist groups, praised the Soviet regime, and contrasted the courage of jailed socialist Eugene V. Debs with the "school boy rhetoric" of traditional black leaders.

The Times characterized the publications as "vicious and apparently well financed," mentioned "certain factions of the radical Socialist elements," and reported it all under the headline: "Reds Try to Stir Negroes to Revolt".

But then the reign of mob law to which he has so long lived in terror and the injustices to which he has had to submit have made him sensitive and impatient.The connection between black people and Bolshevism was widely repeated.

The Times saw "bloodshed on a scale amounting to local insurrection" as evidence of "a new negro problem" because of "influences that are now working to drive a wedge of bitterness and hatred between the two races.

When the Times endorsed Haynes' call for a bi-racial conference to establish "some plan to guarantee greater protection, justice, and opportunity to Negroes that will gain the support of law-abiding citizens of both races", it endorsed discussion with "those negro leaders who are opposed to militant methods.In mid-October government sources provided the Times with evidence of Bolshevist propaganda appealing to America's black communities.

This account set Red propaganda in the black community into a broader context, since it was "paralleling the agitation that is being carried on in industrial centres of the North and West, where there are many alien laborers".

[49] The Times described newspapers, magazines, and "so-called 'negro betterment' organizations" as the way propaganda about the "doctrines of Lenin and Trotzky" was distributed to black people.

"[50] The next day's report added detail: "Additional evidence has been obtained of the activities of propagandists among the negroes, and it is thought that a plot existed for a general uprising against the whites."

"[52] During the Chicago racial violence against people of color the press was incorrectly told by Department of Justice officials that the IWW, socialists, and Bolsheviks were "spreading propaganda to breed race hatred".