Red Scare

A Red Scare is a form of moral panic provoked by fear of the rise, supposed or real, of left-wing ideologies in a society, especially communism and socialism.

The Second Red Scare, which occurred immediately after World War II, was preoccupied with the perception that national or foreign communists were infiltrating or subverting American society and the federal government.

Following the end of the Cold War, unearthed documents revealed substantial Soviet spy activity in the United States, although many of the agents were never properly identified by Senator Joseph McCarthy.

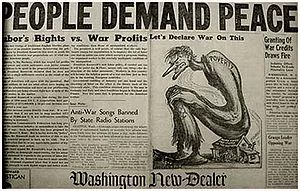

[3] News media exacerbated such fears, channeling them into anti-foreign sentiment due to the lively debate among recent immigrants from Europe regarding various forms of anarchism as possible solutions to widespread poverty.

The IWW and those sympathetic to workers claimed that the press "misrepresented legitimate labor strikes" as "crimes against society", "conspiracies against the government", and "plots to establish communism".

[5] Opponents of labor viewed strikes as an extension of the radical, anarchist foundations of the IWW, which contends that all workers should be united as a social class and that capitalism and the wage system should be abolished.

[6] In June 1917, as a response to World War I, Congress passed the Espionage Act to prevent any information relating to national defense from being used to harm the United States or to aid her enemies.

[7] In April 1919, authorities discovered a plot for mailing 36 bombs to prominent members of the U.S. political and economic establishment: J. P. Morgan Jr., John D. Rockefeller, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, U.S. Attorney General Alexander Mitchell Palmer, and immigration officials.

[9] In 1918, before the bombings, President Woodrow Wilson had pressured Congress to legislate the anti-anarchist Sedition Act of 1918 to protect wartime morale by deporting putatively undesirable political people.

Law professor David D. Cole reports that President Wilson's "federal government consistently targeted alien radicals, deporting them... for their speech or associations, making little effort to distinguish terrorists from ideological dissidents".

[8] President Wilson used the Sedition Act of 1918 to limit the exercise of free speech by criminalizing language deemed disloyal to the United States government.

[14] Passage of these laws, in turn, provoked aggressive police investigation of the accused persons, their jailing, and deportation for being suspected of being either communist or left-wing.

The events of the late 1940s, the early 1950s—the trial of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg (1953), the trial of Alger Hiss, the Iron Curtain (1945–1991) around Eastern Europe, and the Soviet Union's first nuclear weapon test in 1949 (RDS-1)—surprised the American public, influencing popular opinion about U.S. national security, which, in turn, was connected to the fear that the Soviet Union would drop nuclear bombs on the United States, and fear of the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA).

[20] At times, countersubversive anticommunists accused liberals of being "equally destructive" as Communists due to an alleged lack of religious values or supposed "red web" infiltration into the New Deal.

[25] In 1940, soon after World War II began in Europe, the U.S. Congress legislated the Alien Registration Act (also known as the Smith Act, 18 USC § 2385) making it a crime to "knowingly or willfully advocate, abet, advise or teach the duty, necessity, desirability or propriety of overthrowing the Government of the United States or of any State by force or violence, or for anyone to organize any association which teaches, advises or encourages such an overthrow, or for anyone to become a member of or to affiliate with any such association"—and required Federal registration of all foreign nationals.

Although principally deployed against communists, the Smith Act was also used against right-wing political threats such as the German-American Bund, and the perceived racial disloyalty of the Japanese-American population (cf.

After the Soviet Union signed the non-aggression Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany on August 23, 1939, negative attitudes towards communists in the United States were on the rise.

[29] On November 30, when Soviet Union attacked Finland and after forced mutual assistance pacts from Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, the Communist Party considered Russian security sufficient justification to support the actions.

[32] The CPUSA also dropped its boycott of Nazi goods, spread the slogans "The Yanks Are Not Coming" and "Hands Off", set up a "perpetual peace vigil" across the street from the White House and announced that Roosevelt was the head of the "war party of the American bourgeoisie".

Critics of the HUAC claim their tactics were an abuse of government power and resulted in a witch hunt that disregarded citizens’ rights and ruined their careers and reputations.

Critics claim the internal witch hunt was a use for personal gain to spread influence for government officials by intensifying the fear of Communists infiltrating the country.

President Truman declared the act a "mockery of the Bill of Rights" and a "long step toward totalitarianism" because it represented a government restriction on the freedom of opinion.

Simultaneously, some American politicians saw the prospect of American-educated Chinese students bringing their knowledge back to "Red China" as an unacceptable threat to American national security, and laws such as the China Aid Act of 1950 and the Refugee Relief Act of 1953 gave significant assistance to Chinese students who wished to settle in the United States.

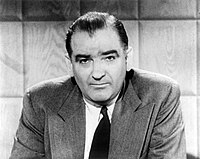

"[41] In 1954, after accusing the army, including war heroes, Senator Joseph McCarthy lost credibility in the eyes of the American public and the Army-McCarthy Hearings were held in the summer of 1954.

[38] After the Senate formally censured McCarthy,[42] his political standing and power were significantly diminished, and much of the tension surrounding the idea of a possible communist takeover died down.

From 1955 through 1959, the Supreme Court made several decisions which restricted the ways in which the government could enforce its anti-communist policies, some of which included limiting the federal loyalty program to only those who had access to sensitive information, allowing defendants to face their accusers, reducing the strength of congressional investigation committees, and weakening the Smith Act.

[44][45] Over 300 American communists, whether they knew it or not, including government officials and technicians that helped in developing the atom bomb, were found to have engaged in espionage.

[49] The CPDC has been criticized as promoting a revival of Red Scare politics in the United States, and for its ties to conspiracy theorist Frank Gaffney and conservative activist Steve Bannon.