Redstone Coke Oven Historic District

Their support steel was removed during the scrap metal drives of World War II, and later they were used as living space by hippies who moved into Redstone.

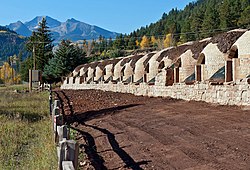

[6] Most of the structures are freestanding beehive ovens made of stone, their rounded tops covered with hardened brown earth.

A set in the middle, just north of the parking area and entrance, is within a stone retaining wall added in the mid-20th century (due to this, neither it nor the ovens it protects are considered to be contributing to the historic district[7]).

[4] The isolation of the Crystal Valley allowed the native Ute people to avoid contact with European colonists until they encountered the Spanish in the late 18th century.

The Astor family began supporting the latter during the next decade, and John C. Frémont led the first American expedition to the valley in 1843, returning two years later.

After the American Civil War, the federal government concluded treaties with the Utes and otherwise began to encourage settlement in the region, that its rich mineral resources might be exploited.

The surveys of Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden in 1873 gave names to many other mountains and streams in the region and suggested the Crystal Valley might well be rich in coal.

[8] Silver and lead strikes led to the establishment of now-abandoned settlements like Crystal and Schofield further up the valley, along the river's upper forks in what is now Gunnison County.

The Panic of 1893 delayed those plans, due to the failure of many of the state's banks and the ensuing difficulty in finding financing, to the end of the decade.

[8] The large work force was often restive, and their strikes hobbled CF&I at a time when it was making major investments in its Pueblo steel plant.

In 1953, some of the ovens near the center of the group were stabilized with a stone retaining wall,[7] when another company, Mid-Continent, began working the coal seams in the creek valley again.

As part of the division of its assets, it was proposed that a convenience store and gas station be built in the middle of the ovens, since the only one that had been on the 60-mile (100 km) stretch of Highway 133 between Carbondale and Paonia had closed.

[4] Residents, led by a member of the local historical society who called the ovens "the soul of Redstone", began working to save them.

Initially, a state grant would have covered the cost, but it would have required an expansion of the historic district, which the landowner did not want, as they would not be able to further develop the site if the deal collapsed.

It made up the difference between the $290,000 purchase price and the original state grant, and the 14 acres (5.7 ha)[4] including the ovens was finally protected.

The plan by the Aspen landscape architecture firm Bluegreen called for rebuilding part of the original wharf used to load and unload the ovens from adjacent railcars.

[4][7] Workers have found some relics of possible archeological interest inside the ovens, such as a pickaxe blade, though it is not known whether they came from the original mining era or the hippie years.