Reflecting instrument

Those that considered the problem realized that the use of specula (mirrors in modern parlance) could permit two objects to be observed in a single view.

What followed is a series of inventions and improvements that refined the instrument to the point that its accuracy exceeded that which was required for determining longitude.

Some of the early reflecting instruments were proposed by scientists such as Robert Hooke and Isaac Newton.

Invented in 1660 by the Dutch Joost van Breen, the spiegelboog (mirror-bow) was a reflecting cross staff.

This instrument appears to have been used for approximately 100 years, mainly in the Zeeland Chamber of the VOC (The Dutch East India Company).

[2] This instrument was first described in 1666 and a working model was presented by Hooke at a meeting of the Royal Society some time later.

Aligning the two objects together in the telescopes view resulted in the angular distance between them to be represented on the graduated chord.

While Hooke's instrument was novel and attracted some attention at the time, there is no evidence that it was subjected to any tests at sea.

The mirror is mounted on the staff (DF) of the radio latino portion of the instrument and rotates with it.

The celestial object's elevation angle could have been determined by reading from graduations on the staff at the slider, however, that's not how Halley designed the instrument.

[3] However, Halley did discuss Newton's design with members of the Royal Society when Hadley presented his reflecting quadrant in 1731.

[2] As a result of this inadvertent secrecy, Newton's invention played little role in the development of reflecting instruments.

What is remarkable about the octant is the number of persons who independently invented the device in a short period of time.

Caleb Smith, an English insurance broker with a strong interest in astronomy, had created an octant in 1734.

However, the other design elements of Smith's instrument made it inferior to Hadley's octant and it was not used significantly.

Fouchy did not know of the developments in England at the time, since communications between the two country's instrument makers was limited and the publications of the Royal Society, particularly the Philosophical Transactions, were not being distributed in France.

Admiral John Campbell, having used Hadley's octant in sea trials of the method of lunar distances, found that it was wanting.

The 90° angle subtended by the arc of the instrument was insufficient to measure some of the angular distances required for the method.

The octant, while occasionally constructed entirely of brass, remained primarily a wooden-framed instrument.

This had a drawback in making the instrument heavier, which could influence the accuracy due to hand-shaking as the navigator worked against its weight.

An earlier version had a second frame that only covered the upper part of the instrument, securing the mirrors and telescope.

Troughton knew William Hyde Wollaston through the Royal Society and this gave him access to the precious metal.

[8] Instruments from Troughton's company that used platinum can be easily identified by the word Platina engraved on the frame.

The reflecting circle was invented by the German geometer and astronomer Tobias Mayer in 1752,[6] with details published in 1767.

Mayer presented a detailed description of this instrument to the Board of Longitude and John Bird used the information to construct one sixteen inches in diameter for evaluation by the Royal Navy.

It was notable as being the equal of the great theodolite created by the renowned instrument maker, Jesse Ramsden.

He made a design with two concentric circles and a vernier scale and recommended averaging three sequential readings to reduce the error.

A disadvantage of reflecting instruments in surveying applications is that optics dictate that the mirror and index arm rotate through half the angular separation of the two objects.

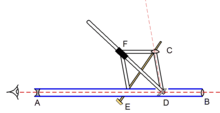

He used a sector as the basis of his instrument and placed the horizon glass at one tip and the index mirror near the hinge connecting the two rulers.

The two revolving elements were linked mechanically and the barrel supporting the mirror was twice the diameter of the hinge to give the required angular ratio.

The index with telescope mounted is shown in black, the radius arm with the mirror (grey) attached in blue and the chord in green on white. The lines of sight are represented by the red dashed line.