Reform Judaism

A highly liberal strand of Judaism, it is characterized by little stress on ritual and personal observance, regarding Jewish law as non-binding and the individual Jew as autonomous, and by a great openness to external influences and progressive values.

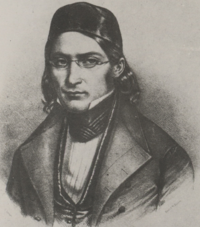

The origins of Reform Judaism lie in mid-19th-century Germany, where Rabbi Abraham Geiger and his associates formulated its early principles, attempting to harmonize Jewish tradition with modern sensibilities in the age of emancipation.

Critics, like Rabbi Dana Evan Kaplan, warned that Reform became more of a Jewish activities club, a means to demonstrate some affinity to one's heritage in which even rabbinical students do not have to believe in any specific theology or engage in any particular practice, rather than a defined belief system.

After critical research led him to regard scripture as a human creation, bearing the marks of historical circumstances, he abandoned the belief in the unbroken perpetuity of tradition derived from Sinai and gradually replaced it with the idea of progressive revelation.

No less importantly, it provided the clergy with a rationale for adapting, changing and excising traditional mores and bypassing the accepted conventions of Jewish Law, rooted in the orthodox concept of the explicit transmission of both scripture and its oral interpretation.

[4][14] In its early days, this notion was greatly influenced by the philosophy of German idealism, from which its founders drew much inspiration: belief in humanity marching toward a full understanding of itself and the divine, manifested in moral progress towards perfection.

However, while granting higher status to historical and traditional understanding, both insisted that "revelation is certainly not Law giving" and that it did not contain any "finished statements about God", but, rather, that human subjectivity shaped the unfathomable content of the Encounter and interpreted it under its own limitations.

The movement maintained the idea of the Chosen People of God, but recast it in a more universal fashion: it isolated and accentuated the notion (already present in traditional sources) that the mission of Israel was to spread among all nations and teach them divinely-inspired ethical monotheism, bringing them all closer to the Creator.

One extreme "Classical" promulgator of this approach, Rabbi David Einhorn, substituted the lamentation on the Ninth of Av for a celebration, regarding the destruction of Jerusalem as fulfilling God's scheme to bring his word, via his people, to all corners of the earth.

When secularist thinkers like Ahad Ha'am and Mordecai Kaplan forwarded the view of Judaism as a civilization, portraying it as a culture created by the Jewish people, rather than a God-given faith defining them, Reform theologians decidedly rejected their position – although it became popular and even dominant among rank-and-file members.

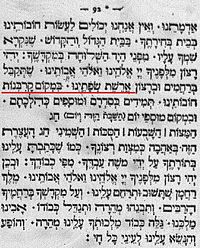

Blessings and passages referring to the coming of the Messiah, return to Zion, renewal of sacrificial practices, resurrection of the dead, reward and punishment and overt particularism of the People Israel were replaced, recast or excised altogether.

Circumcision or Letting of Blood for converts and newborn babies became virtually mandated in the 1980s; ablution for menstruating women gained great grassroots popularity at the turn of the century, and some synagogues built mikvehs (ritual baths).

[44] Steven M. Cohen deduced there were 756,000 adult Jewish synagogue members – about a quarter of households had an unconverted spouse (according to 2001 findings), adding some 90,000 non-Jews and making the total constituency roughly 850,000 – and further 1,154,000 "Reform-identified non-members" in the United States.

The Hamburg reformers, still attempting to play within the limits of rabbinic tradition, cited canonical sources in defence of their actions; they had the grudging support of one liberal-minded rabbi, Aaron Chorin of Arad, though even he never acceded to the removal of prayers for the sacrifices.

As acculturation and resulting religious apathy spread, many synagogues introduced mild aesthetic changes, such as vernacular sermons or somber conduct, yet these were carefully crafted to assuage conservative elements (though the staunchly Orthodox opposed them anyhow; secular education for rabbis, for example, was much resisted).

Apart from strictly aesthetic matters, like having sermons and synagogue affairs delivered in English, rather than Middle Spanish (as was customary among Western Sephardim), they had almost their entire liturgy solely in the vernacular, in a far greater proportion compared to the Hamburg rite.

Having concluded the belief in an unbroken tradition back to Sinai or a divinely dictated Torah could not be maintained, he began to articulate a theology of progressive revelation, presenting the Pharisees as reformers who revolutionized the Saducee-dominated religion.

While the former stressed continuity with the past and described Judaism as an entity that gradually adopted and discarded elements along time, Holdheim accorded present conditions the highest status, sharply dividing the universalist core from all other aspects that could be unremittingly disposed of.

He declared mixed marriage permissible – almost the only Reform rabbi to do so in history; his contemporaries and later generations opposed this – for the Talmudic ban on conducting them on Sabbath, unlike offering sacrifice and other acts, was to him sufficient demonstration that they belonged not to the category of sanctified obligations (issurim) but to the civil ones (memonot), where the Law of the Land applied.

Repeating the response of the 1806 Paris Grand Sanhedrin to Napoleon, it declared intermarriage permissible as long as children could be raised Jewish; this measure effectively banned such unions without offending Christians, as no state in Germany allowed mixed-faith couples to have non-Christians education for offspring.

In the 1850s and 1860s, dozens of new prayerbooks which omitted or rephrased the cardinal theological segments of temple sacrifice, ingathering of exiles, Messiah, resurrection and angels – rather than merely abbreviating the service; excising non-essential parts, especially piyyutim, was common among moderate Orthodox and conservatives too[60] – were authored in Germany for mass usage, demonstrating the prevalence of the new religious ideology.

Secular education for clergy became mandated by mid-century, and yeshivas all closed due to lack of applicants, replaced by modern seminaries; the new academically trained rabbinate, whether affirming basically traditional doctrines or liberal and influenced by Wissenschaft, was scarcely prone to anything beyond aesthetic modifications and de facto tolerance of the laity's apathy.

While fueled by the condition of immigrant communities, in matters of doctrine, wrote Michael Meyer, "However much a response to its particular social context, the basic principles are those put forth by Geiger and the other German Reformers – progressive revelation, historical-critical approach, the centrality of the Prophetic literature.

The leading intellectuals of Eastern European Jewish nationalism castigated western Jews in general, and Reform Judaism in particular, not on theological grounds which they as laicists wholly rejected, but for what they claimed to be assimilationist tendencies and the undermining of peoplehood.

The CCAR soon readopted elements long discarded in order to appeal to them: In the 1910s, inexperienced rabbis in the East Coast were given as shofars ram horns fitted with a trumpet mouthpiece, seventy years after the Reformgemeinde first held High Holiday prayers without blowing the instrument.

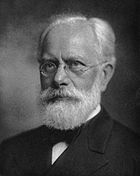

In 1908, Vogelstein and Rabbi Cäsar Seligmann also founded a congregational arm, the Union for Liberal Judaism in Germany (Vereinigung für das Liberale Judentum in Deutschland), finally institutionalizing the current that until then was active as a loose tendency.

Rabbi Jacob K. Shankman wrote they were all "animated by the convictions of Reform Judaism: emphasized the Prophets' teachings as the cardinal element, progressive revelation, willingness to adapt ancient forms to contemporary needs".

Cohon valued Jewish particularism over universalist leanings, encouraging the reincorporation of traditional elements long discarded, not as part of a comprehensive legalistic framework but as means to rekindle ethnic cohesion.

To accommodate all, ten liturgies for morning service and six for the evening were offered for each congregation to choose of, from very traditional to one that retained the Hebrew text for God but translated it as "Eternal Power", condemned by many as de facto humanistic.

In 1978, UAHC President Alexander Schindler admitted that measures aimed at curbing intermarriage rates by various sanctions, whether on the concerned parties or on rabbis assisting or acknowledging them (ordinances penalizing such involvement were passed in 1909, 1947 and 1962), were no longer effective.