Ottoman Tunisia

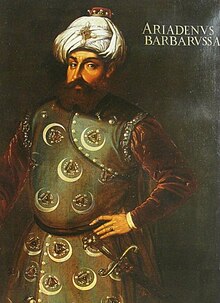

[30][31][32] After gaining combat experience in the eastern Mediterranean (during which Aruj was captured and spent three years rowing in a galley of the Knights of St. John before being ransomed),[33] the two brothers arrived in Tunis as corsair leaders.

[28] In 1516, Aruj and his brother Khayr al-Din, accompanied by Turkish soldiers, ventured further west to Algiers, where they seized control from the shaykh of the Tha'aliba tribe, who had made a treaty with Spain.

[40] Khayr al-Din continued to orchestrate large-scale raids on Christian shipping and the coastal regions of Mediterranean Europe, amassing considerable wealth and taking numerous captives.

[49] In 1569, Uluj Ali Pasha, a renegade corsair,[50][51][52][sentence fragment] advanced with Turkish forces from the west and seized the Spanish presidio Goletta and the Hafsid capital, Tunis.

[53][54] After the key naval victory of the Christian armada at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571,[55][sentence fragment] Don Juan de Austria retook Tunis for Spain in 1573, restoring Hafsid's rule.

But the Turks were nonetheless a powerful ally for Barbary, diverting Christian energies into eastern Europe, threatening Mediterranean communications, and absorbing those forces which might otherwise have turned their attention to reconquest in Africa.

[67][68] When Uluj Ali, the beylerbey of Algiers, passed away in 1587, the Ottoman sultan abolished the position, signifying the normalization of administration in the Maghrebi provinces after the prolonged conflict with Spain.

With the establishment of permanent Ottoman rule in 1574, the government of Tunis gained a degree of stability, contrasting with the insecurity and uncertainty brought by the previous periods of war.

Just four years later, in 1591, a revolt among the occupying Turkish forces, particularly the janissaries, propelled a new military leader, the Dey, to prominence, effectively supplanting the pasha and assuming ruling authority in Tunis.

Neither inclined toward luxury, they directed treasury funds toward public projects and infrastructure development, including the construction of mosques, fortresses, barracks, and the repair of aqueducts.

To aid in this task, the Bey organized rural cavalry (sipahis) as an auxiliary force, primarily composed of Arabs recruited from what became known as "government" (makhzan) tribes.

However, Husayn ibn Ali defied the Dey and garnered support from Tunisian khassa (notables), the ulama (religious scholars), and local tribes, despite being a Turkish-speaking outsider.

During his reign as Bey of Tunis, Husayn b. Ali supported agriculture, particularly the cultivation of olive orchards, and initiated public works projects, including mosques and madrassas (schools).

[95] Early Husaynid policy necessitated a delicate equilibrium among several disparate factions: the distant Ottomans, the Turkish-speaking elite in Tunisia, and local Tunisians (including urban and rural dwellers, notables, clerics, landowners, and remote tribal leaders).

At the apex, a select few prominent families, predominantly Turkish-speaking, were favored with business opportunities, land grants, and key government positions, contingent upon their loyalty.

[103] During this period of colonial rule, the beylical institution was retained, with the Husaynid Bey serving as titular head of state, while the French effectively governed the country.

For instance, Turks crafted their gazi sagas of frontier warfare, drawing inspiration from Islamic traditions of early Arab conquests, yet infused with legends from the steppes of Central Asia.

[106][107][108] Due to the challenges of governance and its extensive geographical reach, the Ottoman state played a pivotal role in shaping Muslim legal developments for centuries.

[109] Imperial law drew from various sources, including Islamic fiqh, Roman-Byzantine legal codes, and the traditions of the great Turkish and Mongol empires of Central Asia.

[110] The Turkish jurist Ebu us-Suud Efendi (c.1490–1574) was credited with harmonizing the regulations of the secular state (qanun) and the sacred law (şeriat) for use in Ottoman courts.

[118][119][120] The arrival of a Turkish-speaking ruling elite in Tunisia, whose institutions held sway over governance for centuries, indirectly influenced the enduring linguistic divide between Berber and Arabic in settled areas.

The activity became highly developed, featuring modes of recruitment, hierarchical structures within the corps, peer review systems, both private and public financing, trades, and material support, as well as coordinated operations and markets for resale and ransom.

[138][139] Crews were sourced from three main groups: Christian renegades, which included many famous or notorious captains, foreign Muslims, primarily Turkish, and a small number of native Maghrebis.

Investors purchased shares in specific Corsair business ventures, drawn from various levels of society, including merchants, officials, janissaries, shopkeepers, and artisans.

First, Algiers received its share as the state representative of Allah; next came the port authorities, customs brokers, and sanctuary keepers; then, the portion due to the ship owners, captain, and crew followed.

The seized merchant cargo was typically sold at auction or, more commonly, to European commercial representatives residing in Algiers, through whom it might even reach its original destination port.

This mosque, initiated by Muhammad Bey and completed under his successor, Ramadan ibn Murad, between 1696 and 1699, showcases a dome system characteristic of Classical Ottoman architecture.

[152]: 226–227 Husayn ibn Ali (r. 1705–1735), the founder of the Husaynid dynasty, oversaw the expansion of the Bardo Palace, the traditional residence of Tunisian rulers dating back to the 15th century.

By exploiting the religious sentiments of the Maghriban Muslims, the Barbarossa brothers were able to establish a foothold in the Maghrib from which they gradually extended into the interior their control, as well as the authority of the Ottoman sultan, which they came to accept.

""[T]he sultan judged the moment suitable to bring the African conquests within the normal framework of the Ottoman organization, and he transformed Tripolitania, Tunisia, and Algeria into three regencies [Trk: Ayala] administered by pashas subject to periodic replacement.