Regular polytope

The strong symmetry of the regular polytopes gives them an aesthetic quality that interests both mathematicians and non-mathematicians.

A concise symbolic representation for regular polytopes was developed by Ludwig Schläfli in the 19th century, and a slightly modified form has become standard.

Their names are, in order of dimension: The process of making each simplex can be visualized on a graph: Begin with a point A.

Mark point D in a third, orthogonal, dimension a distance r from all three, and join to form a regular tetrahedron.

Their names are, in order of dimension: The process of making each hypercube can be visualized on a graph: Begin with a point A.

Their names are, in order of dimensionality: The process of making each orthoplex can be visualized on a graph: Begin with a point O.

Regular polytopes are in bijection with Coxeter groups with linear Coxeter-Dynkin diagram (without branch point) and an increasing numbering of the nodes.

The earliest surviving mathematical treatment of regular polygons and polyhedra comes to us from ancient Greek mathematicians.

The subsequent history of the regular polytopes can be characterised by a gradual broadening of the basic concept, allowing more and more objects to be considered among their number.

It was not until the 19th century that a Swiss mathematician, Ludwig Schläfli, examined and characterised the regular polytopes in higher dimensions.

The term "polytope" was introduced by Reinhold Hoppe, one of Schläfli's rediscoverers, in 1882, and first used in English by Alicia Boole Stott some twenty years later.

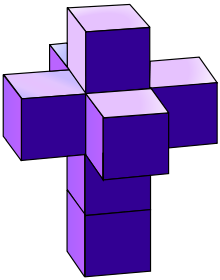

Five of them can be seen as analogous to the Platonic solids: the 4-simplex (or pentachoron) to the tetrahedron, the hypercube (or tesseract) to the cube, the 4-orthoplex (or hexadecachoron or 16-cell) to the octahedron, the 120-cell to the dodecahedron, and the 600-cell to the icosahedron.

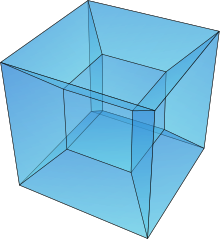

By the end of the 19th century, mathematicians such as Arthur Cayley and Ludwig Schläfli had developed the theory of regular polytopes in four and higher dimensions, such as the tesseract and the 24-cell.

The latter are difficult (though not impossible) to visualise through a process of dimensional analogy, since they retain the familiar symmetry of their lower-dimensional analogues.

The 24-cell can be derived from the tesseract by joining the 8 vertices of each of its cubical faces to an additional vertex to form the four-dimensional analogue of a pyramid.

There is an equivalent (non-recursive) definition, which states that a polytope is regular if it has a sufficient degree of symmetry.

It seems to satisfy the definition of a regular polygon — all the edges are the same length, all the angles are the same, and the figure has no loose ends (because they can never be reached).

By 1994 Grünbaum was considering polytopes abstractly as combinatorial sets of points or vertices, and was unconcerned whether faces were planar.

Certain restrictions are imposed on the set that are similar to properties satisfied by the classical regular polytopes (including the Platonic solids).

The definition of regularity in terms of the transitivity of flags as given in the introduction applies to abstract polytopes.

The traditional way to construct a regular polygon, or indeed any other figure on the plane, is by compass and straightedge.

Since the Platonic solids have only triangles, squares and pentagons for faces, and these are all constructible with a ruler and compass, there exist ruler-and-compass methods for drawing these fold-out nets.

[4] Numerous children's toys, generally aimed at the teen or pre-teen age bracket, allow experimentation with regular polygons and polyhedra.

For example, klikko provides sets of plastic triangles, squares, pentagons and hexagons that can be joined edge-to-edge in a large number of different ways.

Such models are occasionally found in science museums or mathematics departments of universities (such as that of the Université Libre de Bruxelles).

If the hyperplane is moved through the shape, the three-dimensional slices can be combined, animated into a kind of four dimensional object, where the fourth dimension is taken to be time.

Another way a three-dimensional viewer can comprehend the structure of a four-dimensional polytope is through being "immersed" in the object, perhaps via some form of virtual reality technology.

Locally, this space seems like the one we are familiar with, and therefore, a virtual-reality system could, in principle, be programmed to allow exploration of these "tessellations", that is, of the 4-dimensional regular polytopes.

The mathematics department at UIUC has a number of pictures of what one would see if embedded in a tessellation of hyperbolic space with dodecahedra.

Normally, for abstract regular polytopes, a mathematician considers that the object is "constructed" if the structure of its symmetry group is known.