Euclidean tilings by convex regular polygons

Euclidean plane tilings by convex regular polygons have been widely used since antiquity.

The first systematic mathematical treatment was that of Kepler in his Harmonices Mundi (Latin: The Harmony of the World, 1619).

Broken down, 36; 36 (both of different transitivity class), or (36)2, tells us that there are 2 vertices (denoted by the superscript 2), each with 6 equilateral 3-sided polygons (triangles).

With a final vertex 34.6, 4 more contiguous equilateral triangles and a single regular hexagon.

Antwerp v3.0,[4] a free online application, allows for the infinite generation of regular polygon tilings through a set of shape placement stages and iterative rotation and reflection operations, obtained directly from the GomJau-Hogg’s notation.

Note that there are two mirror image (enantiomorphic or chiral) forms of 34.6 (snub hexagonal) tiling, only one of which is shown in the following table.

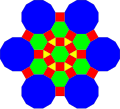

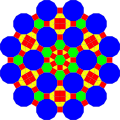

There are 17 combinations of regular convex polygons that form 21 types of plane-vertex tilings.

k-uniform tilings with the same vertex figures can be further identified by their wallpaper group symmetry.

Each can be grouped by the number m of distinct vertex figures, which are also called m-Archimedean tilings.

These higher-order uniform tilings use the same lattice but possess greater complexity.

The fractalizing basis for theses tilings is as follows:[16] The side lengths are dilated by a factor of

Such tilings can be considered edge-to-edge as nonregular polygons with adjacent colinear edges.