Regular tuning

Among alternative guitar-tunings, regular tunings have equal musical intervals between the paired notes of their successive open strings.

The class of regular tunings has been named and described by Professor William Sethares.

There are separate chord-forms for chords having their root note on the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth strings.

Such alternative tuning arrangements offer different chord voicing and sonorities.

For example, all-fifths tuning has been difficult to implement on conventional guitars, due to the extreme high pitch required from the top string.

In contrast, regular tunings have constant intervals between their successive open-strings.

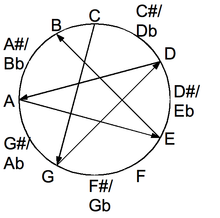

In fact, the class of each regular tuning is characterized by its musical interval as shown by the following list: The regular tunings whose number of semitones s divides 12 (the number of notes in the octave) repeat their open-string notes (raised one octave) after 12/s strings: For example, Regular tunings have symmetrical scales all along the fretboard.

[4] On the other hand, minor-thirds tuning features many barre chords with repeated notes,[5] properties that appeal to beginners.

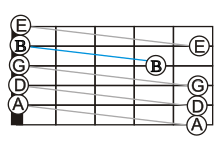

The chromatic scale climbs from one string to the next after a number of frets that is specific to each regular tuning.

The chromatic scale climbs after exactly four frets in major-thirds tuning, so reducing the extensions of the little and index fingers ("hand stretching").

[6] For other regular tunings, the successive strings have intervals that are minor thirds, perfect fourths, augmented fourths, or perfect fifths; thus, the fretting hand covers three, five, six, or seven frets respectively to play a chromatic scale.

(Of course, the lowest chromatic-scale uses the open strings and so requires one less fret to be covered.)

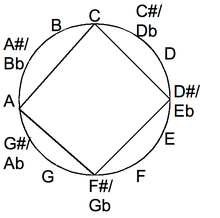

In each minor-thirds (m3) tuning, every interval between successive strings is a minor third.

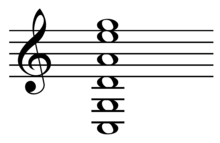

In the minor-thirds tuning beginning with C, the open strings contain the notes (C, E♭, Gb) of the diminished C triad.

[7] Minor-thirds tuning features many barre chords with repeated notes,[5] properties that appeal to acoustic guitarists and to beginners.

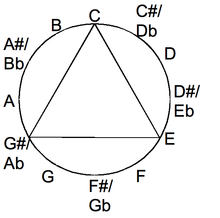

[11][12] With the repetition of three open-string notes, each major-thirds tuning provides the guitarist with many options for fingering chords.

Indeed, the fingering of two successive frets suffices to play pure major and minor chords, while the fingering of three successive frets suffices to play seconds, fourths, sevenths, and ninths.

[4][15] Major-thirds tuning was heavily used in 1964 by the American jazz-guitarist Ralph Patt to facilitate his style of improvisation.

The regularity of chord-patterns reduces the number of finger positions that need to be memorized.

When he was asked whether tuning in fifths facilitates "new intervals or harmonies that aren't readily available in standard tuning", Robert Fripp responded, "It's a more rational system, but it's also better sounding—better for chords, better for single notes."

[27] Some closely voiced jazz chords become impractical in NST and all-fifths tuning.

The high B4 requires a taut, thin string, and consequently is prone to breaking.

This new tuning is like a mirror to all kinds of string instruments including guitar.

The B4 has been replaced with a G4 in the new standard tuning (NST) of King Crimson's Robert Fripp.

[35] For regular tunings, intervals wider than a perfect fifth or narrower than a minor third have, thus far, had limited interest.

In general, the left-handed involute of the regular tuning based on the interval with