Free imperial city

[1] An imperial city held the status of imperial immediacy, and was subordinate only to the Holy Roman Emperor, as opposed to a territorial city or town (Landstadt), which was subordinate to a territorial prince – be it an ecclesiastical lord (prince-bishop, prince-abbot), or a secular prince (duke (Herzog), margrave, count (Graf), etc.).

Those cities, which had been founded by the German kings and emperors in the 10th through 13th centuries and had initially been administered by royal/imperial stewards (Vögte), gradually gained independence as their city magistrates assumed the duties of administration and justice; some prominent examples are Colmar, Haguenau, and Mulhouse in Alsace or Memmingen and Ravensburg in upper Swabia.

[citation needed] The Free Cities (Freie Städte; Urbes liberae) were those, such as Basel, Augsburg, Cologne or Strasbourg, that were initially subjected to a prince-bishop and, likewise, progressively gained independence from that lord.

A few, like Protestant Donauwörth, which in 1607 was annexed to the Catholic Duchy of Bavaria, were stripped by the Emperor of their status as a Free City – for genuine or trumped-up reasons.

The Imperial military tax register (Reichsmatrikel) of 1521 listed eighty-five such cities, and this figure had fallen to 65 by the time of the Peace of Augsburg in 1555.

[4] Reflecting the complex constitutional set-up of the Holy Roman Empire, a third category, composed of semi-autonomous cities that belonged to neither of those two types, is distinguished by some historians.

Having probably learned from experience that there was not much to gain from active, and costly, participation in the Imperial Diet's proceedings due to the lack of empathy of the princes, the cities made little use of their representation in that body.

At the opposite end, the authority of Cologne, Aachen, Worms, Goslar, Wetzlar, Augsburg and Regensburg barely extended beyond the city walls.

[14] Urban conflicts in Free Imperial Cities, which sometimes amounted to class warfare, were not uncommon in the Early Modern Age, particularly in the 17th century (Lübeck, 1598–1669; Schwäbisch Hall, 1601–1604; Frankfurt, 1612–1614; Wezlar, 1612–1615; Erfurt, 1648–1664; Cologne, 1680–1685; Hamburg 1678–1693, 1702–1708).

[15] Sometimes, as in the case of Hamburg in 1708, the situation was considered sufficiently serious to warrant the dispatch of an Imperial commissioner with troops to restore order and negotiate a compromise and a new city constitution between the warring parties.

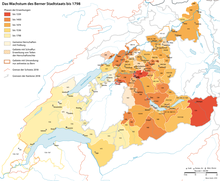

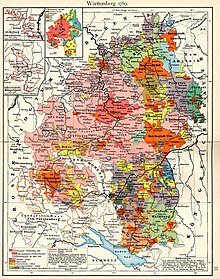

There were more in areas that were very fragmented politically, such as Swabia and Franconia in the southwest, than in the North and the East where the larger and more powerful territories, such as Brandenburg and Saxony, were located, which were more prone to absorb smaller, weaker states.

After 1795, the areas west of the Rhine were annexed to France by the revolutionary armies, suppressing the independence of Imperial Cities as diverse as Cologne, Aachen, Speyer and Worms.

Then, the Napoleonic Wars led to the reorganization of the Empire in 1803 (see German Mediatisation), where all of the free cities but six – Hamburg, Bremen, Lübeck, Frankfurt, Augsburg, and Nuremberg – lost their independence and were absorbed into neighboring territories.

[1] The three other Free Cities became constituent states of the new German Empire in 1871 and consequently were no longer fully sovereign as they lost control over defence, foreign affairs and a few other fields.

In the Federal Republic of Germany which was established after the war, Bremen and Hamburg, but not Lübeck, became constituent states, a status which they retain to the present day.

Berlin, which had never been a Free City in its history, received the status of a state after the war due to its special position in divided post-war Germany.