Religion in Fiji

[3] Aboriginal Fijian religion could be classified in modern terms as forms of animism or shamanism, traditions utilizing various systems of divination which strongly affected every aspect of life.

Fiji has many public holidays as it acknowledges the special days held by the various belief systems, such as Easter and Christmas for the Christians, Diwali for the Hindus and the Eid al-Adha for the Muslims.

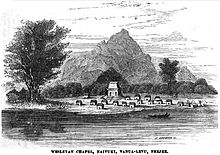

Contact from the early 19th century with European Christian missionaries, especially of the Methodist denomination, saw conversion of dominant chiefs such as Octavia and thus also the people they controlled.

(2) Every person has the right, either individually or in community with others, and both in public and in private, to manifest his or her religion or belief in worship, observance, practice or teaching.

All his life he walked warily for fear of angering the deities that went in and out with him, ever watchful to catch him tripping, and death but cast him naked into their midst to be the sport of their vindictive ingenuity."

In the book "Pacific Irishman", the Anglican priest Charles William Whonsbon-Ashton records in Chapter 1, "Creation":[10] "When I came to Fiji the famed fish-god, the Dakuwaqa, was very much a reality.

The Government ship, the Lady Escott, reached Levuka with signs of an encounter with the great fish, while the late Captain Robbie, a well known, tall, and very erect Scot, even to his nineties, told of the sleepy afternoon as his cutter was sailing from his tea estate at Wainunu, under a very light wind, with most of the crew dozing.

A great fish, which he described as near 60 feet in length, brown-spotted and mottled on its back, with the head of a shark and the tail of a whale, came up under his ship, almost capsizing it.

As late as 1957, R.A Derrick (1957:13) states: "Many Yavusa still venerate a bird (e.g. kingfisher, pigeon, heron), an animal (e.g. dog, rat, or even man), a fish or reptile (e.g. shark, eel, snake), a tree (especially the ironwood or Nokonoko), or a vegetable, claiming one or more of these as peculiarly their own and refusing to injure or eat them.

However, it was more prevalent that certain places or objects like rocks, bamboo clumps, giant trees such as Baka or Ivi trees, caves, isolated sections of the forest, dangerous paths and passages through the reef were considered sacred and home to a particular Kalou-Vu or Kalou-Yalo and were thus treated with respect and a sense of awe and fear, or "Rere", as it was believed they could cause sickness, death, or punish disobedience.

R.A Derrick (1957:11) says: "In these traditions Degei figures not only as the origin of the people, but also as a huge snake, living in a cave near the summit of the mountain Uluda - the northernmost peak of the Nakauvadra Range.

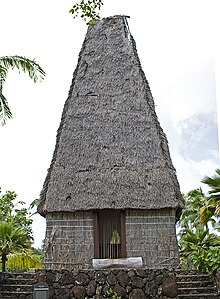

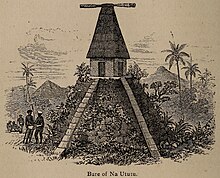

R.A Derrick (1957:10 and 12) notes: "The gods were propitiated to ensure favourable winds for sailing, fruitful seasons, success in war, deliverance from sickness...In times of peace and prosperity, the Bure Kalou might fall into disrepair; but when drought and scarcity came, or war threatened, the god was remembered, his dwelling repaired, its priest overwhelmed with gifts and attention."

Laura Thompson (1940:112) speaking of the situation in Southern Lau states with regard to the Bete: "The priest had charge of the worship of the clan’s ancestor gods (Kalou vu).

The Fijians propitiate the gods for success in war, offspring, deliverance from danger and sickness, fruitful seasons, fine weather, rain, favourable winds, etc., etc.

; but their religious ideas do neither extend to the soul, nor to another world...The influence of the priest over the common people is immense, although he is generally the tool of the chief.

Using various specially decorated natural objects like a conch shell bound in coconut fibre rope or war club, it was a form of divination and was not only in the realm of priests.

A dream where close relatives were seen conveying a message was termed "Kaukaumata" and was an omen warning of an approaching event that may have a negative impact on the dreamer's life.

Martha Kaplan in her book Neither Cargo Nor Cult: Ritual Politics and the Colonial Imagination in Fiji notes: "Seers (Daurai) and dreamers (Dautadra) could predict the future, communicating with deities either in a trance or a dream."

Ana I. González in her web article "Oceania Project Fiji" writes: Mana is a term for a diffuse supernatural power or influence that resides in certain objects or persons and accounts for their extraordinary qualities or effectiveness.

Immediately after death the spirit of the recently departed is believed to remain around the house for four days and after such time it then goes to a jumping off point (a cliff, a tree, or a rock on the beach).

Anthropologist Laura Thompson (1940:115) writes: "The dominant belief...is that when a man dies his soul goes to Nai Thibathiba, a ‘jumping-off’ place found on or near each island, usually facing the west or northwest.

Villagers of the Province of Ra say that he was a trouble maker and was banished from Nakauvadra along with his people; it's been rumored the story was a fabrication of early missionaries.

It is also believed there were three migrations, one led by Lutunasobasoba, one by Degei, and another by Ratu, traditionally known to reside in Vereta, along with numerous regional tales within Fiji that are not covered here and still celebrated and spoken of in story, song and dance.

Also, each chiefly title has its own story of origin, like the Tui Lawa or Ocean Chieftain of Malolo and his staff of power and the Gonesau of Ra who was the blessed child of a Fijian Kalou yalo.

[3] Hinduism in varying forms was the first of the Eastern religions to enter Fiji, with the introduction of the indentured labourers brought by the British authorities from India.

While much of the old religion is now considered not much more than myth, some aspects of witchcraft and the like are still practiced in private, and many of the old deities are still acknowledged, but avoided, as Christianity is followed by the majority of indigenous Fijians.

The constitution further states that religious belief may not be used as an excuse for disobeying the law, and formally limits proselytization on government property and at official events.

[13] Religion, ethnicity, and politics are closely linked in Fiji; government officials have criticized religious groups for their support of opposition parties.

In 2017, the Republic of Fiji Military Forces issued a press release stating that Methodist leaders were advocating for the country to become "a Christian nation" and that this could cause societal unrest.

Later that year, following an online post by an Indian Muslim cleric visiting the country, a significant amount of anti-Muslim discourse was recorded on Fijian Facebook pages, causing controversy.