Religion in Lebanon

Religion amongst registered Lebanese voters (2024)[4] Lebanon differs from other Middle East countries where Muslims have become the majority after the civil war, and somewhat resembles Bosnia-Herzegovina and Albania, both are in Southeast Europe, and have a diverse mix of Muslims and Christians that each make up a large proportion of the country's population.

[12] According to a 2022 analysis by the Pew Research Center, the demographic landscape of Lebanon reveals a Christian population estimated at 43.4%, with Muslims constituting the majority at 57.6%.

This data underscores the religious diversity within Lebanon, reflecting a dynamic interplay of different faith communities within the country.

The confessional breakdown of registered voters in Lebanon between 2011, 2018, and 2024 offers a detailed look at the demographic trends among the country’s various religious sects, including Christians, Muslims (Shias, Sunnis, and Alawites), and Druze.

A general upward trend can be seen in the voter registration figures for Christians, contrasting with the relative stagnation or decline in Muslim sects.

This upward trend, particularly from 2018 onwards, could be linked to the return of displaced individuals and demographic recovery following the initial effects of the 2011 Syrian crisis.

Orthodox communities, largely based in stable urban centers or regions less affected by direct conflict, may have benefited from higher birth rates and lower emigration compared to other groups.

Given Lebanon's relatively stable environment for religious minorities, Armenians have seen a consistent rise in voter registration, suggesting healthy birth rates and potential return migration.

While they constitute a significant portion of the voter base, the overall Muslim population has seen a slight decline as a percentage of the electorate, particularly in areas heavily affected by conflict.

Many Shia residents of southern Lebanon have faced displacement, economic hardship, and lower birth rates due to instability and conflict.

Many Sunni communities reside in regions of Lebanon that have been economically challenged, such as Tripoli and parts of the Bekaa Valley.

These areas have been affected by both internal Lebanese political struggles and the Syrian crisis, which may have led to migration or reduced birth rates.

The Lebanese-Israeli conflicts and their connection to the Assad regime likely contributed to their displacement or migration back to Syria, as many Alawites fled Lebanon due to political instability and threats to their safety.

Their traditional strongholds in the Chouf mountains have largely remained insulated from the worst effects of conflict, allowing their population to grow modestly over time.

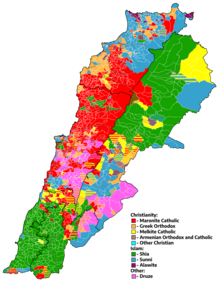

Lebanese Christians form a large proportion of the total population, and they are divided into many branches, including Maronite, Eastern Orthodox, Melkite, and other communities.

Lebanese Muslims form a large number of the total population, and they are divided into many sects, which include Sunnis, Shias, Alawites, and Ismailis.

[citation needed] Lebanese Sunnis are mainly residents of the major cities: west Beirut, Tripoli, and Sidon.

Sunnis are also present in rural areas, which include Akkar, Ikleem al Kharoub, and the western Beqaa Valley.

[26] After the independence from France in 1943, the leaders of Lebanon agreed on the distribution of the political positions in the country according to religious affiliation, known as the National Pact.

[27] Under the terms of an agreement known as the National Pact between the various political and religious leaders of Lebanon, the president of the country must be a Maronite, the prime minister must be a Sunni, and the speaker of Parliament must be a Shia.

Since Lebanon is a country that is ruled by a sectarian system, family matters such as marriage, divorce and inheritance are handled by the religious authorities representing a person's faith.

In the case of Lebanon, many Lebanese couples therefore conducted their civil marriage in Cyprus, which became a well-known destination for such instances.

However, following intense pressure and lobbying by the Civil Center for National Initiative, the Minister of the Interior Ziyad Baroud made it possible to have a citizen's religious sect removed from his identity card in 2009.

In 2011, hundreds of protesters rallied in Beirut on 27 February in a Laïque Pride march, calling for reform of the country's confessional political system.

Religion is encoded on national identity cards and noted on ikhraaj qaid (official registry) documents, and the Government complies with requests of citizens to change their civil records to reflect their new religious status.

[41] Unrecognized groups, such as Baháʼís, Buddhists, Hindus, and some evangelical denominations, may own property and assemble for worship without government interference.