Religion in Turkey

When Turkey eventually applied to join the European Union some member states questioned whether a Muslim country would fit in.

[4] While the state is officially secular, all primary and secondary schools have been required to teach religious studies since 1982, and the curriculum focuses mainly on Sunni Islam.

Beginning in the 1980s, the role of religion in the state has been a divisive issue, as influential religious factions challenged the complete secularization called for by Kemalism and the observance of Islamic practices experienced a substantial revival.

[5] In the early 2000s, Islamic groups challenged the concept of a secular state with increasing vigour after Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's Islamist-rooted Justice and Development Party (AKP) came into power in 2002.

[14] Christians (Oriental Orthodoxy, Greek Orthodox and Armenian Apostolic) and Jews (Sephardi), who comprise the non-Muslim religious population, make up about 0.2% of the total.

Closely related to Alevism is the small Bektashi community belonging to a Sufi order of Islam that is indigenous to Turkey, but also has numerous followers in the Balkan peninsula.

[1][2][4][12] Alevism, which is the dominant sect of Shia Islam in Turkey, is mostly concentrated in the provinces of Tunceli, Erzincan Malatya, Sivas, Çorum, Kahramanmaraş, Amasya and Tokat.

[106] A sizeable part of the autochthonous Yazidi population of Turkey fled the country for present-day Armenia and Georgia starting from the late 19th century.

[124][126] For decades, the wearing of religious headcover and similar theopolitical symbolic garments was prohibited in universities and other public contexts such as military or police service.

[127] As a specific incarnation of an otherwise abstract principle, it accrued symbolic importance among both proponents and opponents of secularism and became the subject of various legal challenges[128] before being dismantled in a series of legislative acts from 2010 to 2017.

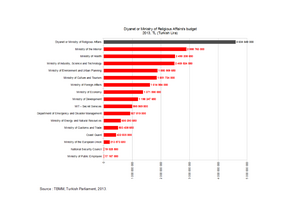

Despite its official secularism, the Turkish government includes the state agency of the Presidency of Religious Affairs (Turkish: Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı),[130] whose purpose is stated by law "to execute the works concerning the beliefs, worship, and ethics of Islam, enlighten the public about their religion, and administer the sacred worshiping places".

Beginning in the 1980s, the role of religion in the state has been a divisive issue, as influential religious factions challenged the complete secularization called for by Kemalism and the observance of Islamic practices experienced a substantial revival.

In the early 2000s (decade), Islamic groups challenged the concept of a secular state with increasing vigor after Recep Tayyip Erdoğan's Islamist-rooted Justice and Development Party (AKP) came into power in 2002.

[134] The mainstream Hanafite school of Sunni Islam is largely organised by the state, through the Presidency of Religious Affairs (Turkish: Diyanet İşleri Başkanlığı), which controls all mosques and pays the salaries of all Muslim clerics.

The 2009 U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom report placed Turkey on its watchlist with countries such as Afghanistan, Cuba, the Russian Federation, and Venezuela.

Despite this, concerns have arisen in recent years because of attacks by extremists on synagogues in 2003, as well as growing anti-Semitism in some sectors of the Turkish media and society.

In February 2006, an Italian Catholic priest was shot to death in his church in Trabzon, reportedly by a youth angered over the caricatures of Muhammad in Danish newspapers.

According to newspaper reports, the assailant, who was arrested soon afterward, admitted that he had been influenced by a recent television program that depicted Christian missionaries as "infiltrators" who took advantage of poor people.

Under current restrictions, only the Sunni Muslim community can legally operate institutions to train new clergy in Turkey for future leadership.

Religiosity among Turkish People (KONDA Research, 2021)[146] In a poll conducted by Sabancı University in 2006, 98.3% of Turks revealed they were Muslim.

The New York Times published a report about Turkey in 2012, noting an increased polarization between secular and religious groups in Turkish society and politics.

[154] Turkish academic Ayhan Kaya, in his 2015 research article Islamisation of Turkey under the AKP Rule: Empowering Family, Faith and Charity, summarizes the question by talking of "a subtle Islamisation of society and politics in everyday life through the debates on the headscarf issue, Imam Hatip schools, faith communities and Alevism, the rise of an Islamic bourgeoisie with its roots in Anatolian culture, the emergence of consumerist lifestyles, not only among the secular segments of the Turkish society but also among Islamists, and, finally, the weakening of the legitimacy of the Turkish military as ‘the guardian of national unity and the laicist order’.

"[156] In a 2022 book chapter, Turkish political scientist S. Erdem Aytaç, while analyzing different nationally representative polls and surveys from 2002, when the AKP rule began, till 2018, when the latest data was available, noted "an increase in subjective religiosity during the AKP rule", as the share of "non-devout" respondents fell from 44% in 2002 to 28% in 2018 while the "devout" rose from 32% to 42% and the "very devout" from 24% to 30% during these years.

[157] The government of Erdoğan and the AKP pursue the explicit policy agenda of Islamization of education to "raise a devout generation" against secular resistance,[158][159] in the process causing lost jobs and school for many non-religious citizens of Turkey.

[160] In 2013, several books that were previously recommended for classroom use were found to be rewritten to include more Islamic themes, without the Ministry of Education's consent.

[161] For most of the 20th century, Turkish law prohibited the wearing of headscarves and similar garments of religious symbolism in public governmental institutions.

[128] Subsequently, the issue formed a core of Recep Tayyip Erdogan's first campaign for the presidency in 2007, arguing that it was an issue of human rights and freedoms[164][165] Following his victory, the ban was eliminated in a series of legislative acts starting with an amendment to the constitution in 2008 allowing women to wear headscarves in Turkish universities while upholding the prohibition of symbols of other religions in that context.

[162][166][167] Further changes saw the ban eliminated in some government buildings including parliament the next year, followed by the police forces and, finally, the military in 2017.

In early July 2020, the Council of State annulled the Cabinet's 1934 decision to establish the museum, revoking the monument's status, and a subsequent decree by Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan ordered the reclassification of Hagia Sophia as a mosque.

[188] However, in the 2023 report Faith and Religiosity in Türkiye, the authors, who say that "a significant portion of society, particularly younger individuals, believes in God but distances themselves from religious institutions and practices", conclude that despite deism having some attraction among university students in particular (highest of 15% among BA students), in the overall society "the prevalence of deism in Türkiye is estimated to be less than 2%.