Religiosity and education

For example, one international study states that in some Western nations the intensity of beliefs decreases with education, but attendance and religious practice increases.

[1] They concluded that "these cross-country differences in the education-belief relationship can be explained by political factors (such as communism) which lead some countries to use state controlled education to discredit religion".

[3] A survey conducted by the Times of India revealed that 22% of IIT Bombay graduates do not believe in the existence of God, while another 30% do not know.

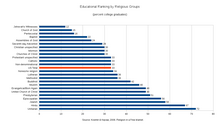

He found that Hindus, Jews, Episcopalians,[17][18] Presbyterians, Buddhists, and Orthodox Christians[19] have the highest levels of education.

[20] Sociological research by Patricia Snell and Christian Smith on many dimensions of general American youth have noted that older research on baby boomers showed correlations where higher education undermined religiosity, however, studies on today's youth have consistently shown that this has disappeared and now students in college are more likely religious than people who do not go to college.

For instance, there are slight differences in belief in God and membership in a congregation: 88% of those with postgraduate degrees believe in God or a universal spirit, compared to 97% of those with a high school education or less; 70% of postgraduate degree holders say they are members of a congregation, compared to 64% of those with a high school education or less.

[21] Research done by Barry Kosmin indicates that Americans with post-graduate education have a similar religious distribution and affiliation to the general population, with a higher "public religiosity" (i.e., membership in congregations and worship attendance), but slightly less "belief."

[22] Research done by Barry Kosmin and Ariela Keysar on college students looked at three worldviews — Religious, Secular, and Spiritual — and looked students from levels from freshmen to post-graduates from majors such as STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics), Social and Behavioral Sciences, Arts and Humanities, and Undecided.

As a whole, university professors were less religious than the general US population, but it is hardly the case that the professorial landscape is characterized by an absence of religion.

Furthermore, the authors noted, "religious skepticism represents a minority position, even among professors teaching at elite research universities.

[24] A study noted positive correlations, among nonreligious Americans, between levels of education and not believing in a deity.

[25] Frank Sulloway of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Michael Shermer of the California State University conducted a study that found in their polling sample of "credentialed" U.S. adults (12% had Ph.Ds and 62% were college graduates) 64% believed in God, and there was a correlation indicating that religious conviction diminished with education level.

[2] Sociologist Philip Schwadel found that higher levels of education "positively affects religious participation, devotional activities, and emphasizing the importance of religion in daily life", education is not correlated with disbelief in God, and correlates with greater tolerance for atheists' public opposition to religion and greater skepticism of "exclusivist religious viewpoints and biblical literalism".

[29][30] Cross-national sociological research by Norris and Inglehart notes a positive correlation between religious attendance among the more educated in the United States.

[31] According to a Pew Center study, about 77% of American Hindus have a graduate and post-graduate degree, followed by Unitarian Universalists (67%), Jews (59%), Anglican (59%), Episcopalians (56%) and Presbyterians (47%) and United Church of Christ (46%).

A 2006 study by Barry Kosmin and Ariela Keysar ranked the three most college educated religious groups as Unitarian Universalists (72%), Hindus (67%), and Jews (57%).