Repatriation and reburial of human remains

Atkinson explains that repatriation will help to soothe the generational pain that resulted from the massacres and collections.

Historically, Indigenous people have experienced massacres and the loss of their children to residential schools.

She notes that the unethical sourcing and study of remains without permission is considered a civil rights violation.

[10] Indigenous Australians' remains were removed from graves, burial sites, hospitals, asylums and prisons from the 19th century through to the late 1940s.

Official figures do not reflect the true state of affairs, with many in private collections and small museums.

[12][11][13] As of April 2019[update], it was estimated that around 1,500 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ancestral remains had been returned to Australia in the previous 30 years.

[15] As of November 2018, the museum had the remains of 660 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people stored in their "secret sacred room" on the fifth floor.

[17] In April 2019, work began to return more than 50 ancestral remains from five different German institutes, starting with a ceremony at the Five Continents Museum in Munich.

Whilst many remains had been shipped overseas by its 1890s director Edward C. Stirling, many more were the result of land clearing, construction projects or members of the public.

The remains, which had been stored in the Grassi Museum of Ethnology in Leipzig, showed signs of head wounds and malnutrition, a reflection of the poor conditions endured by Aboriginal people forced to work on the pearling boats in the 19th century.

The Yawuru and Karajarri people are still in negotiations with the Natural History Museum in London to enable the release of the skull of the warrior known as Gwarinman.

[19] On 1 August 2019, the remains of 11 Kaurna people which had been returned from the UK were laid to rest at a ceremony led by elder Jeffrey Newchurch at Kingston Park Coastal Reserve, south of the city of Adelaide.

[20] In March 2020, a documentary titled Returning Our Ancestors was released by the Victorian Aboriginal Heritage Council based on the book Power and the Passion: Our Ancestors Return Home (2010) by Shannon Faulkhead and Uncle Jim Berg,[21] partly narrated by award-winning musician Archie Roach.

[22][23] In November 2021, the South Australian Museum apologised to the Kaurna people for having taken their ancestors' remains, and buried 100 of them a new 2 ha (4.9-acre) site at Smithfield Memorial Park, donated by Adelaide Cemeteries.

[29] In 2018 the Ministry for Culture and Heritage published a report on Human Remains in New Zealand Museums[30] and The New Zealand Repatriation Research Network was established for museums to work together to research the provenance of remains and assist repatriation.

It was discovered that Päts had been granted a formal burial service, fitting of his office, near Kalinin (now Tver).

[43] The British anthropologist Alfred Cort Haddon removed 13 skulls from a graveyard on Inishmore, and more skulls from Inishbofin, County Galway,[44][45] and a graveyard in Ballinskelligs, County Kerry, as part of the Victorian-era study of "racial types".

[48] On 24 February 2023, Trinity College Dublin confirmed that the human remains, including 13 skulls, in their possession would be returned to Inishbofin.

[49] This process is to formally begin in July 2023, with similar repatriation of remains at St. Finian's Bay and Inishmore to be started later in the year.

[50] The name "El Negro" refers to a dead African man who was taxidermized and displayed in the Darder Museum in Banyoles, Spain.

It wasn't until 1992 when Banyoles was hosting the summer Olympics that people complained of the displayed and taxidermized human remains.

[51][52] It was removed from public display as part of redevelopment work in the late 2010s early 2020s although Byrne’s skeleton was retained in the museum collection to allow for future research.

In 2006 Paul Davies requested that the Alexander Keiller Museum in Avebury, Wiltshire rebury their Neolithic human remains, and that storing and displaying them was "immoral and disrespectful".

[54][55] The archaeological community has voiced criticism of the Neo-druids, making statements such as "no single modern ethnic group or cult should be allowed to appropriate our ancestors for their own agendas.

Their families have long gone, taking all memory with them, and we archaeologists, by bringing them back into the world, are perhaps the nearest they have to kin.

Reburying human remains destroys people and casts them into oblivion: this is at best, misguided, and at worse cruel."[56]Mr.

Davies thanked English Heritage for their time and commitment given to the whole process and concluded that the dialogue used within the consultation focussed on museum retention and not reburial as requested.

Baartman's genitalia, brain, and skeleton were displayed in the Musee de l'Homme in Paris until repatriation to South Africa in 2002.

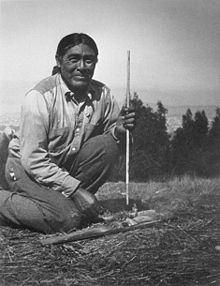

[61] The Kennewick Man is the name generally given to the skeletal remains of a prehistoric Paleoamerican man found on a bank of the Columbia River in Kennewick, Washington, United States, on 28 July 1996,[62][63] which became the subject of a controversial nine-year court case between the United States Army Corps of Engineers, scientists, the Umatilla people and other Native American tribes who claimed ownership of the remains.

[64] The remains of Kennewick Man were finally removed from the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture on 17 February 2017.