Corn Laws

The Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, a Conservative, achieved repeal in 1846 with the support of the Whigs in Parliament, overcoming the opposition of most of his own party.

[8][11] The issue however remained one of public debate (by figures such as Edmund Burke) into the 1790s;[12] and amendments to the 1773 act, favouring agricultural producers, were made in both 1791 and 1804.

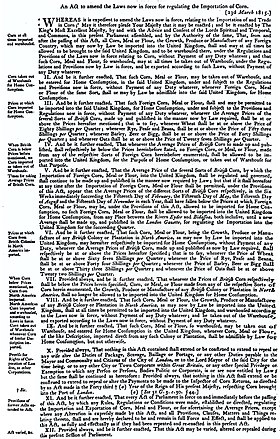

[16] With the advent of peace when the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, corn prices decreased, and the Tory government of Lord Liverpool passed the Importation Act 1815 (55 Geo.

However the Liberal Whig MP Charles Pelham Villiers proposed motions for repeal in the House of Commons every year from 1837 to 1845.

In 1840, under Villiers' direction, the Committee on Import Duties published a blue book examining the effects of the Corn Laws.

In 1842, in response to the Blue book published by Villiers' 1840 Committee on Import Duties, Peel offered a concession by modifying the sliding scale.

In 1842,[22] Peel's fellow-Conservative Monckton Milnes said, at the time of this concession, that Villiers was "the solitary Robinson Crusoe sitting on the rock of Corn Law repeal".

According to historian Asa Briggs, the Anti-Corn Law League was a large, nationwide middle-class moral crusade with a Utopian vision; its leading advocate Richard Cobden promised that repeal would settle four great problems simultaneously: First, it would guarantee the prosperity of the manufacturer by affording him outlets for his products.

The only barrier to these four beneficent solutions was the ignorant self-interest of the landlords, the "bread-taxing oligarchy, unprincipled, unfeeling, rapacious and plundering.

"[24]The landlords claimed that manufacturers like Cobden wanted cheap food so that they could reduce wages and thus maximise their profits, an opinion shared by socialist Chartists.

[28]The magazine The Economist was founded in September 1843 by politician James Wilson with help from the Anti-Corn Law League; his son-in-law Walter Bagehot later became its editor.

In February 1844, the Duke of Richmond initiated the Central Agricultural Protection Society (CAPS, commonly known as the "Anti-League") to campaign in favour of the Corn Laws.

[30] Peel argued in Cabinet that tariffs on grain should be rescinded by Order in Council until Parliament assembled to repeal the Corn Laws.

On 22 November 1845 the Whig Leader of the Opposition Lord John Russell announced in an open letter to the electors in the City of London his support for immediate Corn Law repeal and called upon the government to take urgent action to avert famine.

[31][32] The appearance of Russell's letter spurred Peel and the free-traders in his cabinet to press ahead with repeal measures over the objections of their protectionist colleagues.

[33] On 4 December 1845, an announcement appeared in The Times that the government had decided to recall Parliament in January 1846 to repeal the Corn Laws.

In the rural counties the CAPS was practically supplanting the local Conservative associations and in many areas the independent free holding farmers were resisting the most fiercely.

He said that the Corn Laws would be abolished on 1 February 1849 after three years of gradual reductions of the tariff, leaving only a 1 shilling duty per quarter.

In his resignation speech he attributed the success of repeal to Cobden: In reference to our proposing these measures, I have no wish to rob any person of the credit which is justly due to him for them.

Scholars have advanced several explanations to resolve the puzzle of why Peel made the seemingly irrational decision to sacrifice his government to repeal the Corn Laws, a policy which he had long opposed.

Lusztig (1995) argues that his actions were sensible when considered in the context of his concern for preserving aristocratic government and a limited franchise in the face of threats from popular unrest.

Peel was concerned primarily with preserving the institutions of government, and he considered reform as an occasional necessary evil to preclude the possibility of much more radical or tumultuous actions.

[48] Robert Ensor wrote that these years witnessed the ruin of British agriculture, "which till then had almost as conspicuously led the world, [and which] was thrown overboard in a storm like an unwanted cargo" due to "the sudden and overwhelming invasion ... by American prairie-wheat in the late seventies.

"[49] Previously, agriculture had employed more people in Britain than any other industry and until 1880 it "retained a kind of headship", with its technology far ahead of most European farming, its cattle breeds superior, its cropping the most scientific and its yields the highest, with high wages leading to higher standard of living for agricultural workers than in comparable European countries.

[47] However, after 1877 wages declined and "farmers themselves sank into ever increasing embarrassments; bankruptcies and auctions followed each other; the countryside lost its most respected figures", with those who tended the land with greatest pride and conscience suffering most as the only chance of survival came in lowering standards.

[51] The Prime Minister at the time, Disraeli, had once been a staunch upholder of the Corn Laws and had predicted ruin for agriculture if they were repealed.

[50] Robert Blake said that Disraeli was dissuaded from reviving protection due to the urban working class enjoying cheap imported food at a time of industrial depression and rising unemployment.

Many emigrants were small under-capitalised grain farmers who were squeezed out by low prices and inability to increase production or adapt to the more complex challenge of raising livestock.

These changes occurred at the same time that emigration was reducing the labour supply and increasing wage rates to levels too great for arable farmers to sustain.

[58] During the First World War, the Germans in their U-boat campaign attempted to take advantage of this by sinking ships importing food into Britain, but they were eventually defeated.