Republic of Serbian Krajina

The RSK government waged a war for ethnic Serb independence from Croatia and unification with the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Republika Srpska (in Bosnia and Herzegovina).

Its main portion was overrun by Croatian forces in 1995 and the Republic of Serbian Krajina was ultimately disbanded as a result; a rump remained in eastern Slavonia under UNTAES administration until its peaceful reintegration into Croatia in 1998 under the Erdut Agreement.

The Austrians controlled the Frontier from military headquarters in Vienna and did not make it a crown land, though it had some special rights in order to encourage settlement in an otherwise deserted, war-ravaged territory.

Between 1939 and 1941, in an attempt to resolve the Croat-Serb political and social antagonism in first Yugoslavia, the Kingdom established an autonomous Banovina of Croatia incorporating (amongst other territories) much of the former Military Frontier as well as parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

In 1941, the Axis powers invaded Yugoslavia and in the aftermath the Independent State of Croatia (which included the whole of today's Bosnia and Herzegovina and parts of Serbia (Eastern Syrmia) as well) was declared.

Josip Broz Tito suppressed the autonomous political organizations of the region (along with other movements such as the Croatian Spring); however, the Yugoslav constitutions of 1965 and 1974 did give substantial rights to national minorities - including to the Serbs in SR Croatia.

The Serbian "Krajina" entity to emerge upon Croatia's declaration of independence in 1991 would include three kinds of territories: Large sections of the historical Military Frontier lay outside of the Republic of Serbian Krajina and contained a largely Croat population - these including much of Lika, the area centered around the city of Bjelovar, central and south-eastern Slavonia.

It listed a series of grievances against the Yugoslav federation, claiming that the situation in Kosovo was genocide, and complained about alleged discrimination of Serbs at the hands of the Croatian authorities.

On 8 July 1989, a large nationalist rally was held in Knin, during which banners threatening JNA intervention in Croatia, as well as Chetnik iconography was displayed.

The Constitution of Croatia was passed in December 1990, which reduced the status of Serbs from "constituent" to a "national minority" in the same category as other groups such as Italians and Hungarians.

At his ICTY trial in 2004, he claimed that "during the events [of 1990–1992], and in particular at the beginning of his political career, he was strongly influenced and misled by Serbian propaganda, which repeatedly referred to the imminent threat of a Croatian genocide perpetrated on the Serbs in Croatia, thus creating an atmosphere of hatred and fear of Croats.

"[20] The rebel Croatian Serbs established a number of paramilitary militia units under the leadership of Milan Martić, the police chief in Knin.

[24] Other Serb-dominated communities in eastern Croatia announced that they would also join SAO Krajina and ceased paying taxes to the Zagreb government, and began implementing its own currency system, army regiments, and postal service.

Around August 1991, the leaders of Serbian Krajina and Serbia allegedly agreed to embark on a campaign which the ICTY prosecutors described as a "joint criminal enterprise" whose purpose "was the forcible removal of the majority of the Croat and other non-Serb population from approximately one-third of the territory of the Republic of Croatia, an area he planned to become part of a new Serb-dominated state.

[26] Paramilitary groups such as the Wolves of Vučjak and White Eagles, funded by the Serbian secret police, were also a key component of this structure.

The total number of exiled Croats and other non-Serbs range from 170,000 (ICTY)[30] up to a quarter of a million people (Human Rights Watch).

[31] In the latter half of 1991, Croatia was beginning to form an army and their main defenders, the local police, were overpowered by the JNA military who supported rebelled Croatian Serbs.

[28] Among other places, they shelled the Croatian coastal town of Zadar killing over 80 people in nearby areas and damaging the Maslenica Bridge that connected northern and southern Croatia, in the Operation Coast-91.

The JNA officially withdrew from Croatia in May 1992 but much of its weaponry and many of its personnel remained in the Serb-held areas and were turned over to the RSK's security forces.

UNPROFOR was deployed throughout the region to maintain the ceasefire, although in practice its light armament and restricted rules of engagement meant that it was little more than an observer force.

[33] Milan Babić later testified that this policy was driven from Belgrade through the Serbian secret police—and ultimately Milošević—who he claimed was in control of all the administrative institutions and armed forces in the Krajina.

The Army of Serbian Krajina frequently attacked neighboring Bihać enclave (then in the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina) with heavy artillery.

[46][47] In January 1993 the revitalized Croatian army attacked the Serbian positions around Maslenica in southern Croatia which curtailed their access to the sea via Novigrad.

In response, around 4,000 paramilitaries under the command of Vojislav Šešelj (the White Eagles) and "Arkan" (the Serb Volunteer Guard) arrived to bolster the VSK.

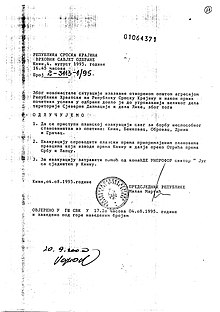

A decision was reached at 16:45 to "start evacuating the population unfit for military service from the municipalities of Knin, Benkovac, Obrovac, Drniš and Gračac."

[55] In 1995 a Croatian court sentenced former RSK president Goran Hadžić in absentia to 20 years in prison for rocket attacks on Šibenik and Vodice.

[60] Former RSK president Milan Babić was indicted for war crimes by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) in 2004 and was the first ever indictee to plead guilty and enter a plea bargain with the prosecution, after which he was sentenced to 13 years in prison.

The indictment and the subsequent trial on charges of crimes against humanity and violations of the laws or customs of war described several killings, widespread arson and looting committed by Croatian soldiers.

However, Serbia did not accept the conclusions of the commission in that period and recognized Croatia only after Croatian military actions (Oluja and Bljesak) and the Dayton agreement.

On 20 November 1991 Lord Carrington asked Badinter commission: "Does the Serbian population in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, as one of the constituent peoples of Yugoslavia, have the right to self-determination?"