Residue theorem

In complex analysis, the residue theorem, sometimes called Cauchy's residue theorem, is a powerful tool to evaluate line integrals of analytic functions over closed curves; it can often be used to compute real integrals and infinite series as well.

be a simply connected open subset of the complex plane containing a finite list of points

is a positively oriented simple closed curve,

is equal to the sum of a set of integrals along paths

each enclosing an arbitrarily small region around a single

we recover the final expression of the contour integral in terms of the winding numbers

In order to evaluate real integrals, the residue theorem is used in the following manner: the integrand is extended to the complex plane and its residues are computed (which is usually easy), and a part of the real axis is extended to a closed curve by attaching a half-circle in the upper or lower half-plane, forming a semicircle.

The integral over this curve can then be computed using the residue theorem.

Often, the half-circle part of the integral will tend towards zero as the radius of the half-circle grows, leaving only the real-axis part of the integral, the one we were originally interested in.

Suppose a punctured disk D = {z : 0 < |z − c| < R} in the complex plane is given and f is a holomorphic function defined (at least) on D. The residue Res(f, c) of f at c is the coefficient a−1 of (z − c)−1 in the Laurent series expansion of f around c. Various methods exist for calculating this value, and the choice of which method to use depends on the function in question, and on the nature of the singularity.

According to the residue theorem, we have: where γ traces out a circle around c in a counterclockwise manner and does not pass through or contain other singularities within it.

We may choose the path γ to be a circle of radius ε around c. Since ε can be as small as we desire it can be made to contain only the singularity of c due to nature of isolated singularities.

If c is a simple pole of f, the residue of f is given by: If that limit does not exist, then f instead has an essential singularity at c. If the limit is 0, then f is either analytic at c or has a removable singularity there.

If the limit is equal to infinity, then the order of the pole is higher than 1.

For higher-order poles, the calculations can become unmanageable, and series expansion is usually easier.

For essential singularities, no such simple formula exists, and residues must usually be taken directly from series expansions.

arises in probability theory when calculating the characteristic function of the Cauchy distribution.

It resists the techniques of elementary calculus but can be evaluated by expressing it as a limit of contour integrals.

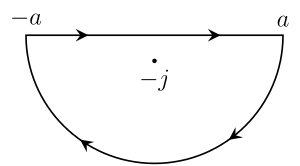

Suppose t > 0 and define the contour C that goes along the real line from −a to a and then counterclockwise along a semicircle centered at 0 from a to −a.

Take a to be greater than 1, so that the imaginary unit i is enclosed within the curve.

Since eitz is an entire function (having no singularities at any point in the complex plane), this function has singularities only where the denominator z2 + 1 is zero.

The contour C may be split into a straight part and a curved arc, so that

The estimate on the numerator follows since t > 0, and for complex numbers z along the arc (which lies in the upper half-plane), the argument φ of z lies between 0 and π.

If t < 0 then a similar argument with an arc C′ that winds around −i rather than i shows that

(If t = 0 then the integral yields immediately to elementary calculus methods and its value is π.)

The fact that π cot(πz) has simple poles with residue 1 at each integer can be used to compute the sum

Let ΓN be the rectangle that is the boundary of [−N − 1/2, N + 1/2]2 with positive orientation, with an integer N. By the residue formula,

on the left and right side of the contour, and so the integrand has order

, since in this case, the residue at zero vanishes, and we obtain the useless identity

The same trick can be used to establish the sum of the Eisenstein series: