Retreat from Gettysburg

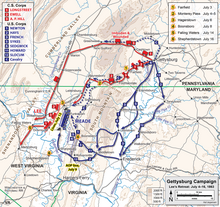

Following General Robert E. Lee's failure to defeat the Union Army at the Battle of Gettysburg (July 1–3, 1863), he ordered a retreat through Maryland and over the Potomac River to relative safety in Virginia.

The Union Army of the Potomac, commanded by Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, was unable to maneuver quickly enough to launch a significant attack on the Confederates, who crossed the river on the night of July 13 into South Mountain through Cashtown in a wagon train that extended for 15–20 miles, enduring harsh weather, treacherous roads, and enemy cavalry raids.

The culmination of the three-day Battle of Gettysburg was the massive infantry assault known as Pickett's Charge, in which the Confederate attack against the center of the Union line on Cemetery Ridge was repulsed with significant losses.

His ability to supply his army by living off the Pennsylvania countryside was now significantly reduced and the Union could easily bring up additional reinforcements as time passed, whereas he could not.

He decided to send his long train of wagons carrying equipment and supplies, which had been captured in great quantities throughout the campaign, to the rear as quickly as possible, in advance of the infantry.

Four miles downstream at Falling Waters, Union cavalry dispatched from Harpers Ferry by Maj. Gen. William H. French destroyed Lee's lightly guarded pontoon bridge on July 4.

In addition to the battle losses, Meade's army was plagued by a condition that persisted during the war, the departure of men and regiments whose enlistments had expired, which took effect even in the midst of an active campaign.

Including the forces around Harpers Ferry, Maryland Heights, and the South Mountain passes, by July 14 between 11,000 and 12,000 men had been added the army, although Meade had extreme doubts about the combat effectiveness of these troops.

[9] Lee's Army of Northern Virginia retained its corps organization and commanders, although a number of key subordinate generals were killed or mortally wounded (Lewis Armistead, Richard B. Garnett, Isaac E. Avery, and William Barksdale), captured (James L. Kemper and James J. Archer), or severely wounded (John Bell Hood, Wade Hampton, George T. Anderson, Dorsey Pender, and Alfred M.

Lee and Stuart had a poor opinion of Imboden's brigade, considering it "indifferently disciplined and inefficiently directed," but it was effective for assignments such as guard duty or fighting militia.

Imboden's orders were to depart Cashtown on the evening of July 4, turn south at Greenwood, avoiding Chambersburg, take the direct road to Williamsport to ford across the Potomac, and escort the train as far as Martinsburg.

The journey was one of extreme misery, conducted during the torrential rains that began on July 4, in which the wounded men were forced to endure the weather and the rough roads in wagons without suspensions.

Departing in the dark, Lee had the advantage of getting several hours head start and the route from the west side of the battlefield to Williamsport was about half as long as the ones available to the Army of the Potomac.

[13] Meade was reluctant to begin an immediate pursuit because he was unsure whether Lee intended to attack again and his orders continued that he was required to protect the cities of Baltimore and Washington, D.C.

Reacting to a report from a local civilian that there was a Confederate forage train near Fairfield, Merritt dispatched about 400 men in four squadrons from the 6th U.S. Cavalry under Major Samuel H. Starr to seize the wagons.

Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren take a division from Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick's VI Corps—the most lightly engaged of all the Union corps at Gettysburg—to probe the Confederate line and determine Lee's intentions.

Meade ordered Butterfield to prepare for a general movement of the army, which he organized into three wings, commanded by Sedgwick (I, III, and VI Corps), Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum (II and XII), and Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard (V and XI).

Gen. George A. Custer to charge the Confederates with the 6th Michigan Cavalry, which broke the deadlock and allowed Kilpatrick's men to reach and attack the wagon train.

Meade immediately halted his army and early on the morning of July 6, he ordered Sedgwick to resume his reconnaissance to determine Lee's intentions and the status of the mountain passes.

Sedgwick argued with him about the risky nature of sending his entire corps into the rugged country and dense fog ahead of him and by noon Meade abandoned his plan, resuming his original intention of advancing east of the mountains to Middletown, Maryland.

The delays leaving Gettysburg and the conflicting orders to Sedgwick about whether to conduct merely a reconnaissance or a vigorous advance to engage Lee's army in combat would later cause Meade political difficulties as his opponents charged him with indecision and timidity.

[20] In view of Sedgwick's lack of aggressiveness in the advance to Fairfield his remark after the campaign that Meade in his pursuit "might have pushed Lee harder" seems singularly inappropriate.

Before Meade's infantry began to march in earnest in pursuit of Lee, Buford's cavalry division departed from Frederick to destroy Imboden's train before it could cross the Potomac.

Col. Thomas C. Devin's dismounted Union cavalry brigade attacked about 8 a.m. By mid-afternoon, with Buford's cavalrymen running low on ammunition and gaining little ground, Col. Lewis A.

French's command sent troops to destroy the railroad bridge at Harpers Ferry and a brigade to occupied Maryland Heights, which prevented the Confederates from outflanking the lower end of South Mountain and threatening Frederick from the southwest.

The Confederate Army's rear guard arrived in Hagerstown on the morning of July 7, screened skillfully by their cavalry, and began to establish defensive positions.

By July 11 they occupied a 6-mile line on high ground with their right resting on the Potomac River near Downsville and the left about 1.5 miles southwest of Hagerstown, covering the only road from there to Williamsport.

Cavalry under Buford and Kilpatrick attacked the rearguard of Lee's army, Maj. Gen. Henry Heth's division, which was still on a ridge about a mile and a half from Falling Waters.

On July 23, Meade ordered French's III Corps to cut off the retreating Confederate columns at Front Royal, by forcing passage through Manassas Gap.

He also suffered humiliation at the hands of his political enemies in front of the Joint Congressional Committee on the Conduct of the War, questioning his actions at Gettysburg and his failure to defeat Lee during the retreat to the Potomac.