Rehabilitation trial of Joan of Arc

On 7 July 1456, the original trial was judged to be invalid due to improper procedures, deceit, and fraud, and the charges against Joan were nullified.

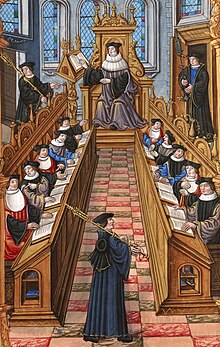

[2] On 15 February 1450, Charles VII ordered the clergyman Guillaume Bouillé, a theologian at the University of Paris, to open an enquiry to address the faults and abuses of the original trial.

[4] Yet, there were many prominent people who had willingly collaborated with the English in 1430 who had subsequently changed their allegiance after Charles had regained Paris and Rouen, and such persons had much to lose if Joan's case was reopened.

[4] They included men such as Jean de Mailly, now the Bishop of Noyon, who had converted to Charles' cause in 1443, but in 1431 had signed letters in the name of King Henry VI of England, guaranteeing English protection to all those who had participated in the case against Joan.

[5] An even greater obstacle was Raoul Roussel, archbishop of Rouen, who had been a fervent supporter of the English cause in Normandy and had participated in Joan's trial, until he, too, took an oath of loyalty to Charles in 1450.

[11] This argument, that the condemnation of Joan had stained the king's honor, was enthusiastically taken up two years later by a man keen to make a good impression of Charles VII—the cardinal Guillaume d'Estouteville.

At d'Estouteville's inquiry of May 1452, two vital but highly placed witnesses were not called—Raoul Roussel, archbishop of Rouen and Jean Le Maître, vicar of the Inquisition in 1431.

Addressing a petition to the new pope, Callixtus III, with help from d'Estouteville who was the family's representative in Rome,[21] they demanded the reparation of Joan's honor, a redress of the injustice she suffered and the citation of her judges to appear before a tribunal.

[22] In response to this plea, Callixtus appointed three members of the French higher clergy to act in concert with Inquisitor Bréhal to review the case and pass judgment as required.

[25] Joan's family were present, and Isabelle made an impassioned speech which began: "I had a daughter born in lawful wedlock, whom I had furnished worthily with the sacraments of baptism and confirmation and had reared in the fear of God and respect for the tradition of the Church ... yet although she never did think, conceive, or do anything whatever which set her out of the path of the faith ... certain enemies ... had her arraigned in religious trial ... in a trial perfidious, violent, iniquitous, and without shadow of right ... did they condemn her in a fashion damnable and criminal, and put her to death very cruelly by fire ... for the damnation of their souls and in notorious, infamous, and irreparable damage done to me, Isabelle, and mine".

[28] The witnesses included many of the tribunal members who had placed her on trial; a couple dozen of the villagers who had known her during her childhood; a number of the soldiers who had served during her campaigns; citizens of Orleans who had met her during the lifting of the siege; and many others who provided vivid and emotional details of Joan's life.

We, in session of our court and having God only before our eyes, say, pronounce, decree and declare that the said trial and sentence (of condemnation) being tainted with fraud (dolus malus), calumny, iniquity and contradiction, and manifest errors of fact and of law ... to have been and to be null, invalid, worthless, without effect and annihilated ... We proclaim that Joan did not contract any taint of infamy and that she shall be and is washed clean of such".

[33] Joan's elderly mother lived to see the final verdict announced, and was present when the city of Orleans celebrated the event by giving a banquet for Inquisitor Bréhal on 27 July 1456.

[32] Although Isabelle's request for punishment against the tribunal members did not materialize, nonetheless the appellate verdict cleared her daughter of the charges that had hung over her name for twenty-five years.